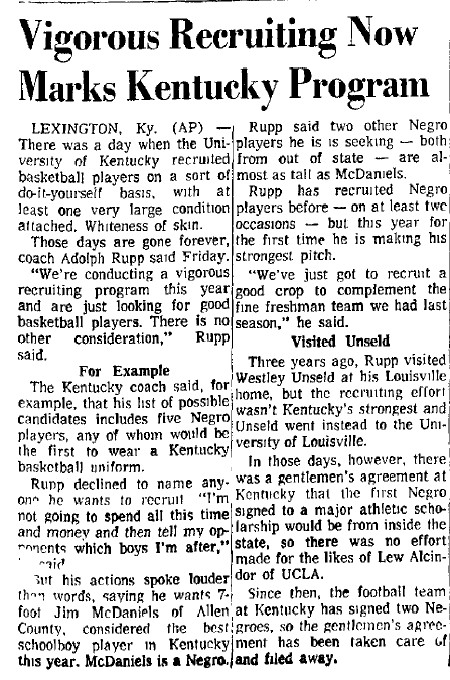

![]()

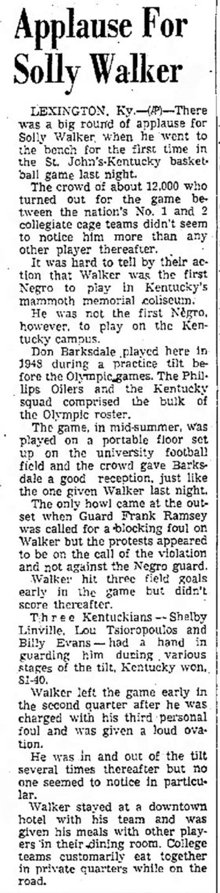

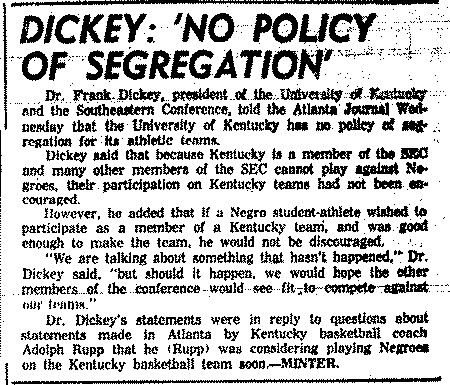

Misconception

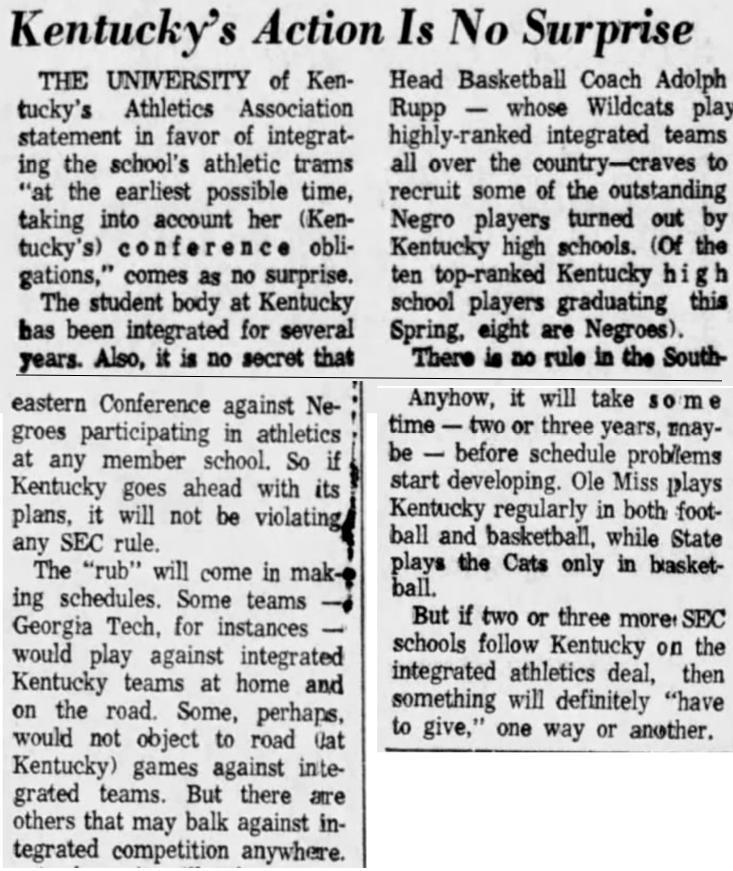

Adolph Rupp was the biggest racist on the planet. He was the end all and be all of evil in college basketball. He had the audacity to coach a Kentucky team that didn't have a single black player against Texas Western which had five black starters. He deserved to lose that game and all his collegiate wins are tarnished because he's so filled with hate.

Adolph Rupp was the biggest racist on the planet. He was the end all and be all of evil in college basketball. He had the audacity to coach a Kentucky team that didn't have a single black player against Texas Western which had five black starters. He deserved to lose that game and all his collegiate wins are tarnished because he's so filled with hate.

![]()

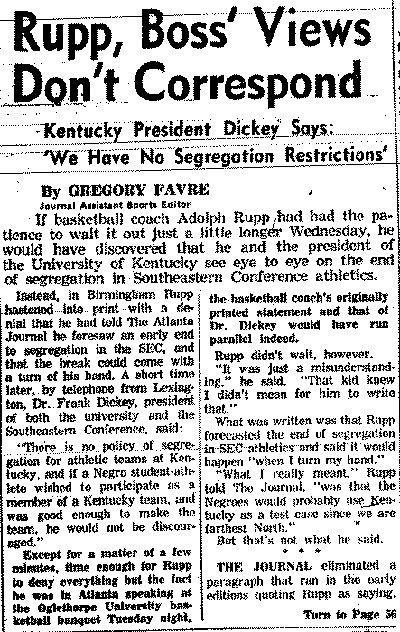

The Facts

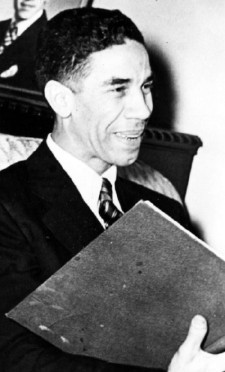

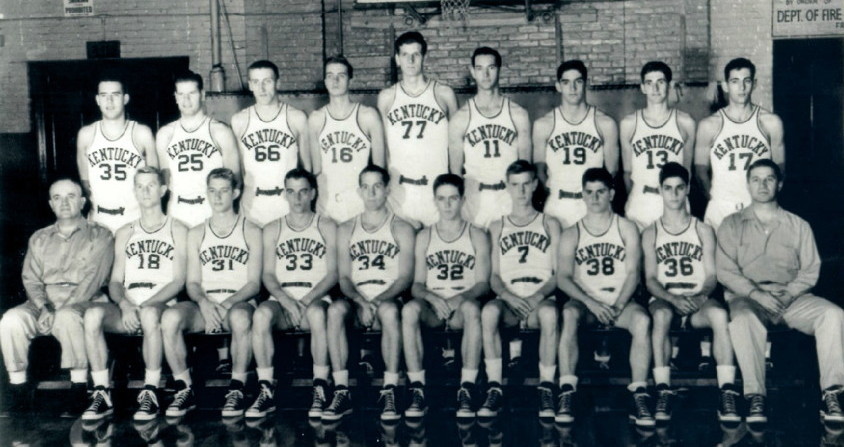

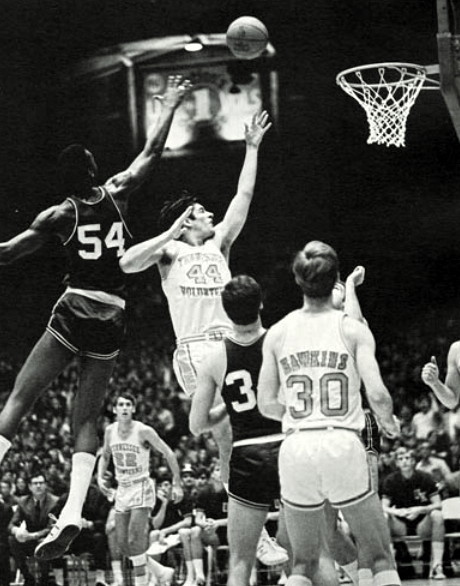

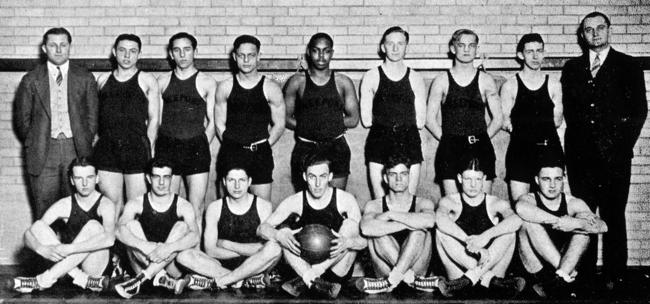

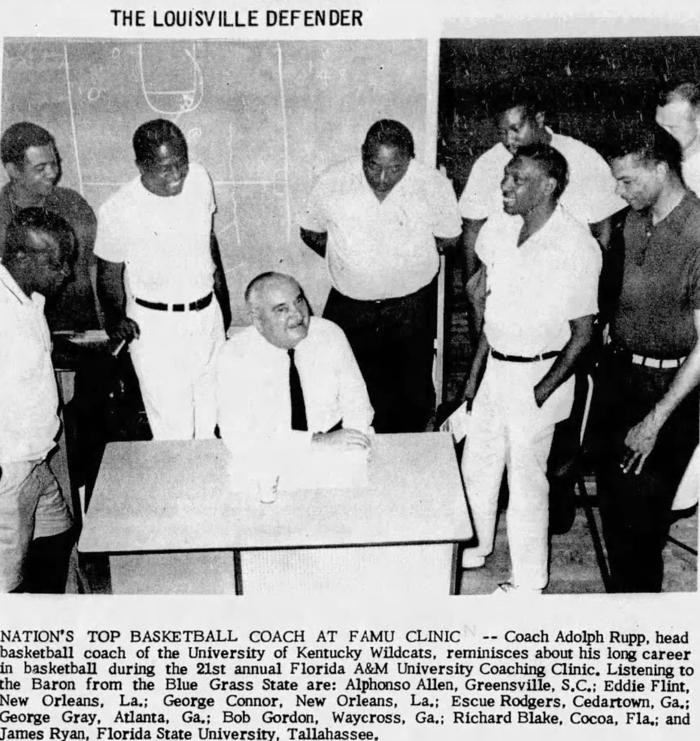

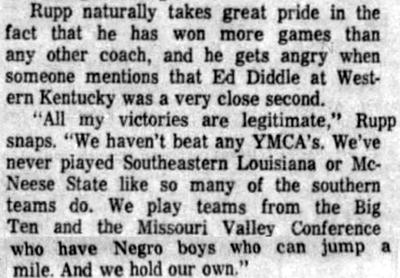

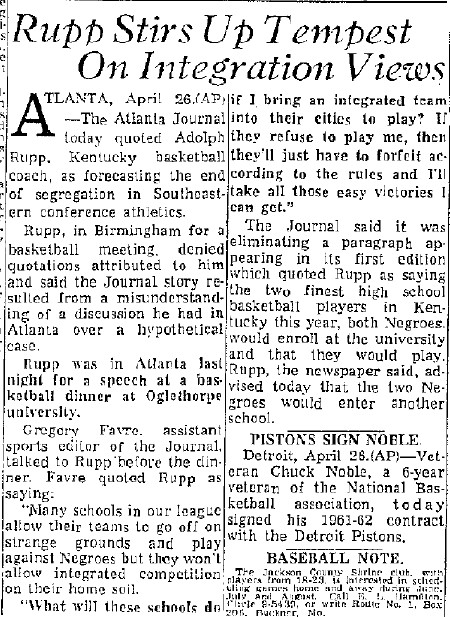

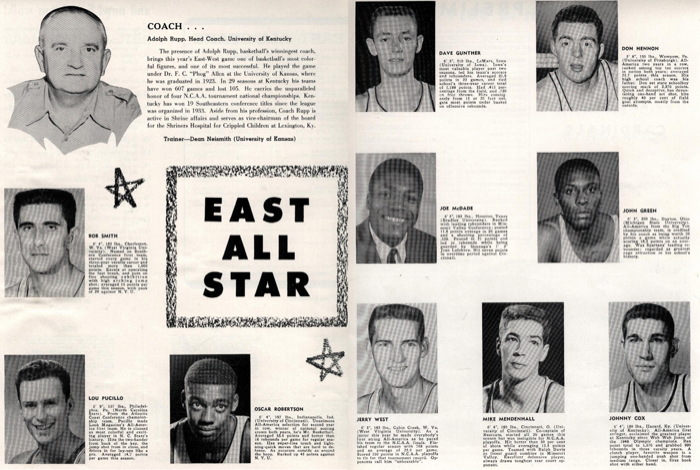

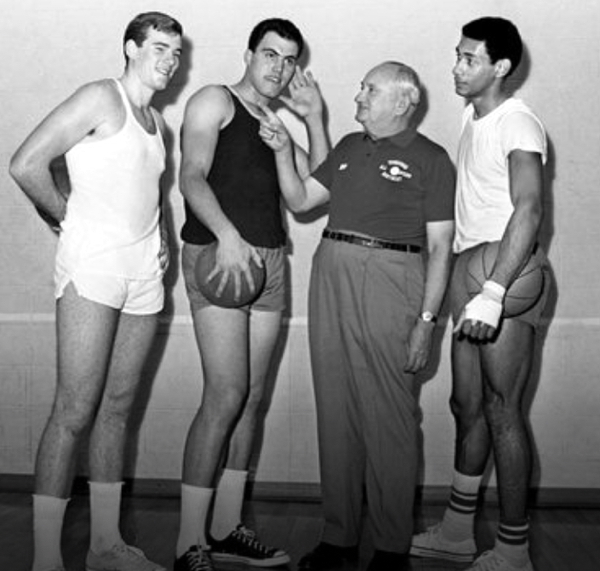

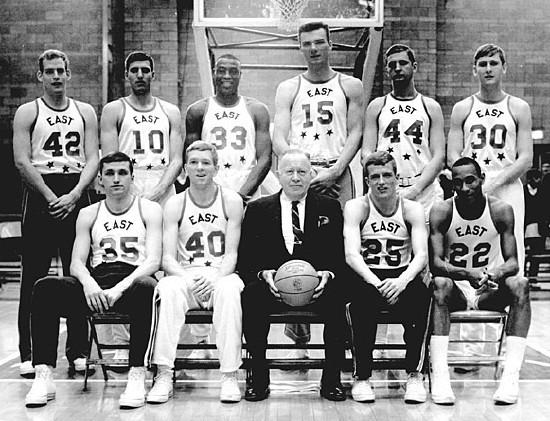

Adolph Rupp coached the Kentucky Wildcats from 1930 to 1972. During that time, he won an unprecedented 876 victories, winning four national championships, twenty-seven SEC championships (82.2% winning) and turning Kentucky into one of the greatest collegiate basketball programs of all time.

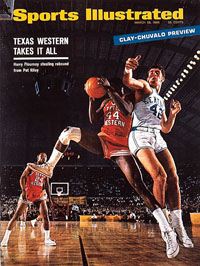

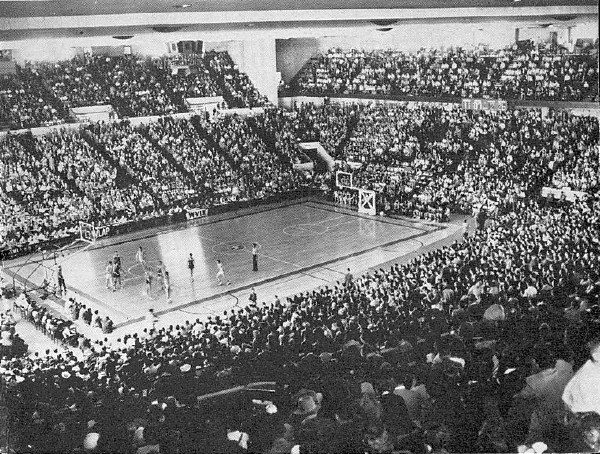

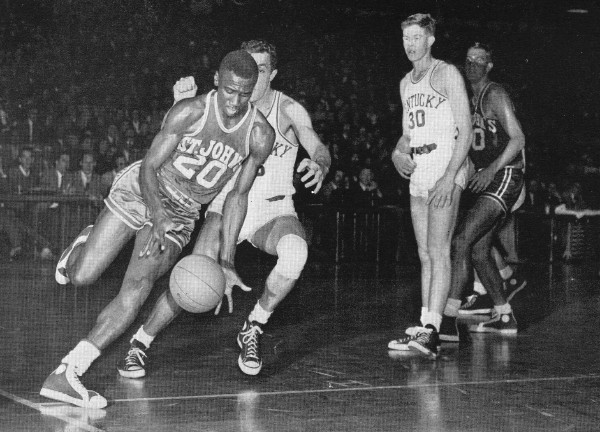

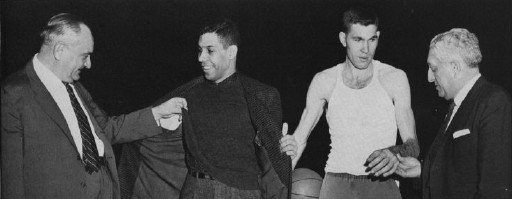

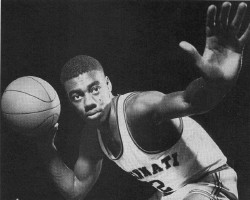

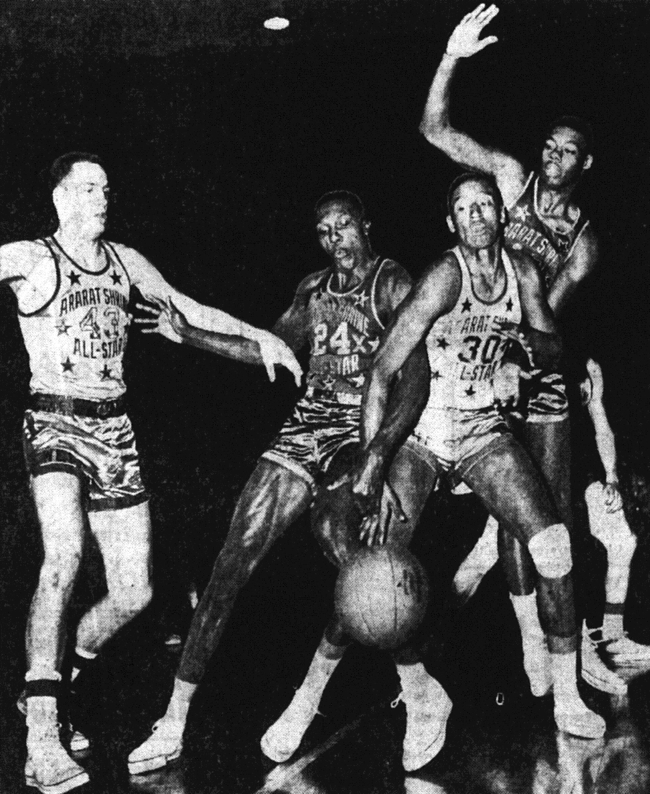

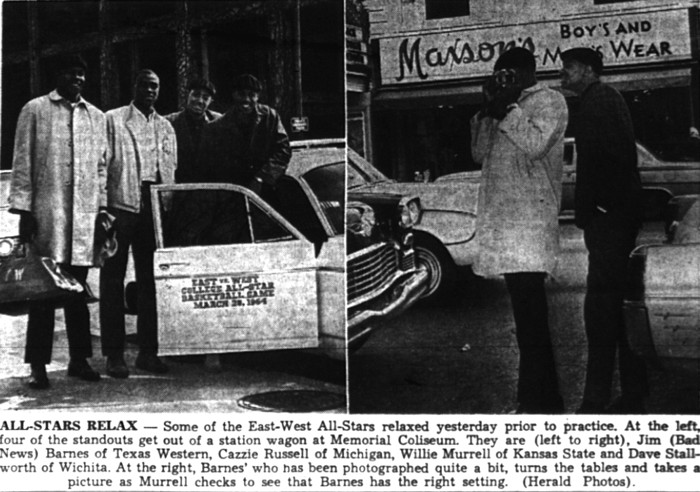

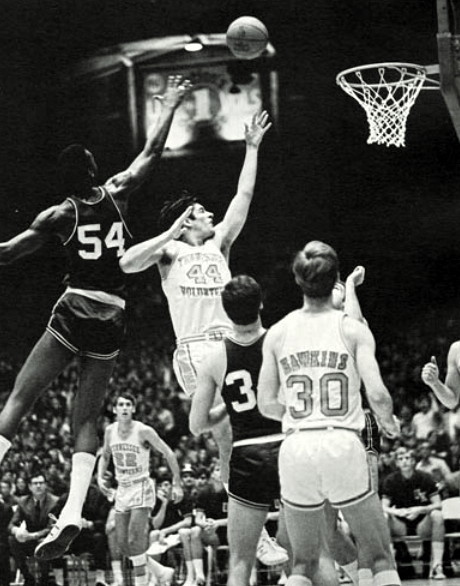

One of the most memorable and important games during Rupp's career was the 1966 championship game against Texas Western (now University of Texas-El Paso). That game marked the first occurrence that an all-white starting five (Kentucky) played an all-black starting five (Texas Western) in the championship game. Texas Western won the game in a hard-fought victory, 72-65. This was especially significant as it came at a time when the civil rights movement came into full swing around the country.

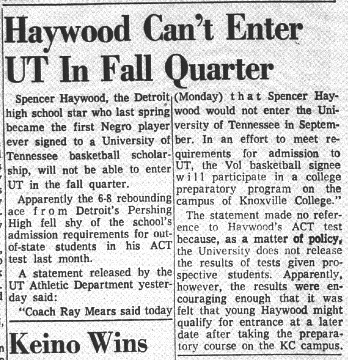

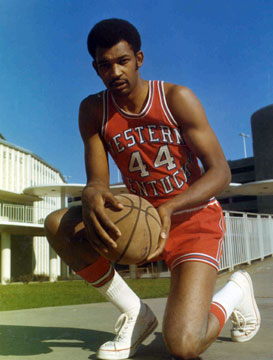

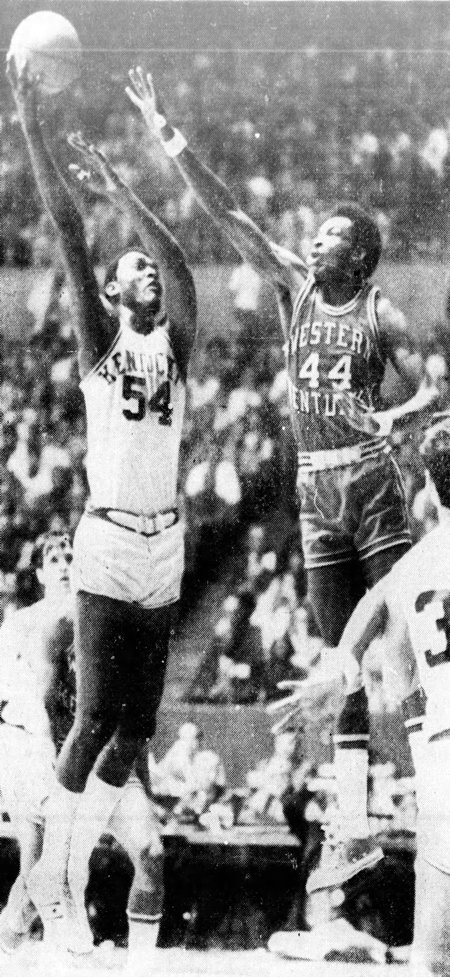

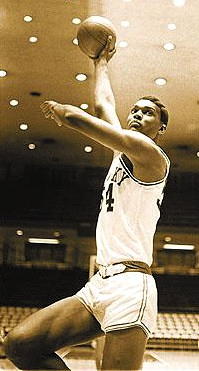

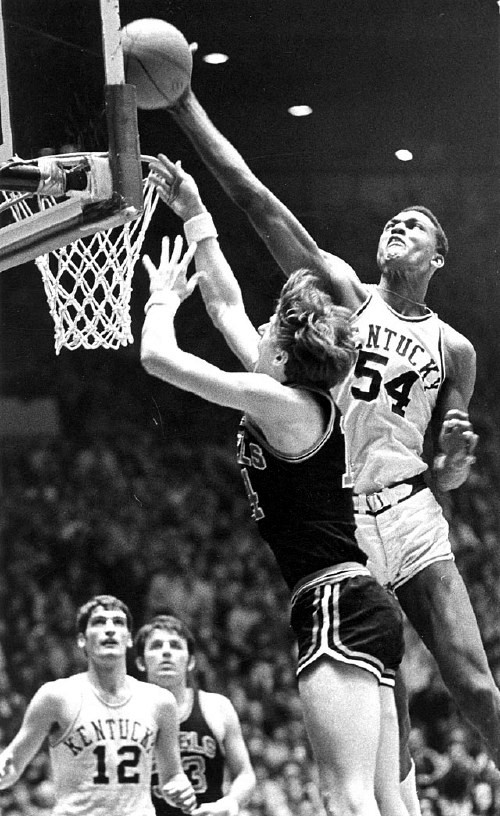

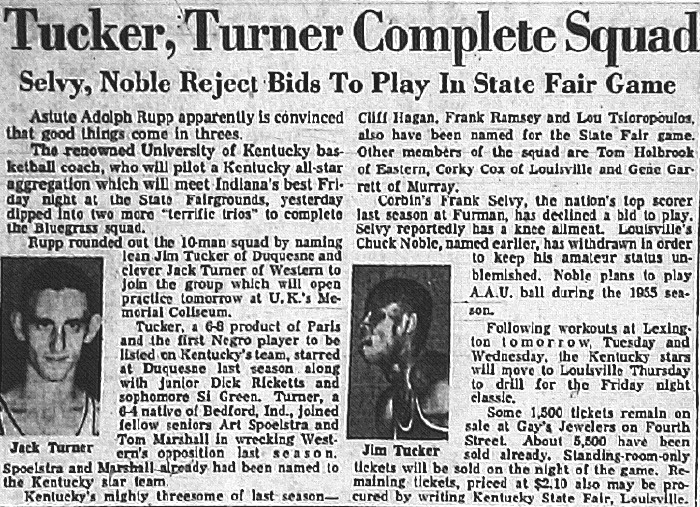

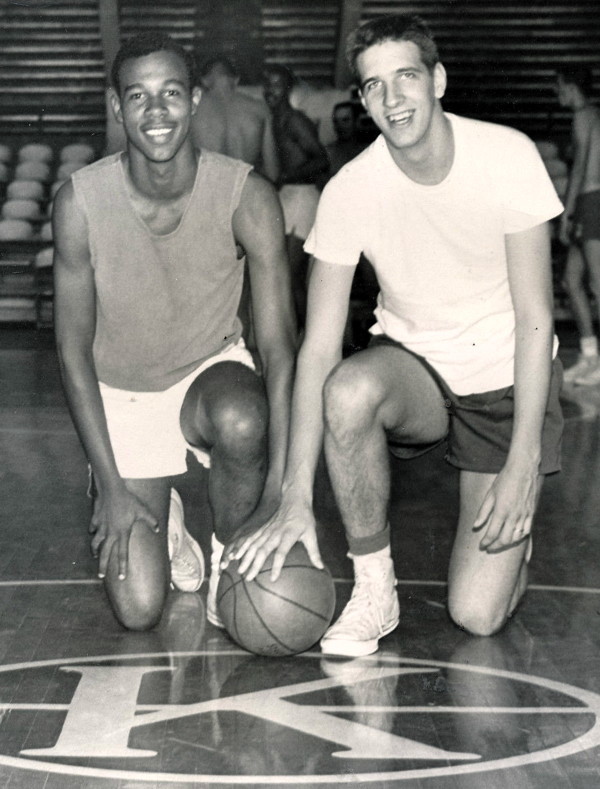

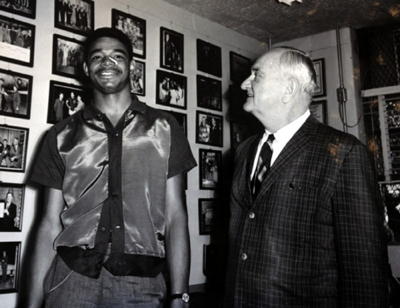

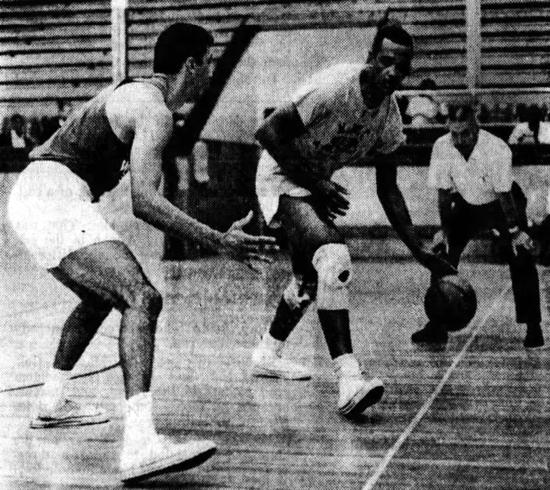

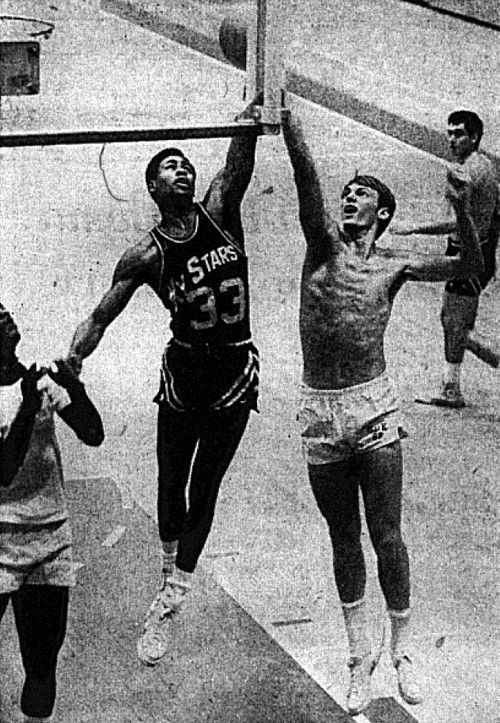

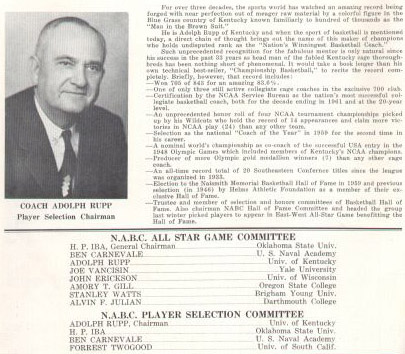

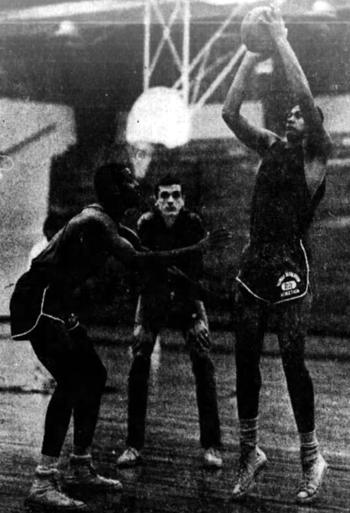

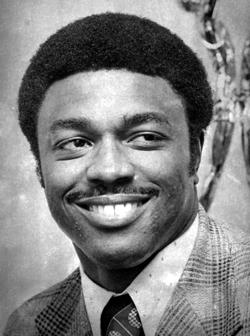

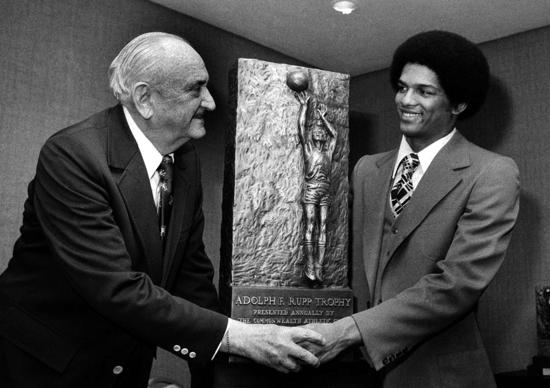

In 1969 Rupp signed Tom Payne, an athletic 7'-2" center out of Louisville. This ended the aspect of all-white Kentucky teams forever and marked a new era with black Kentucky basketball legends including Jack Givens, Sam Bowie, Kenny Walker, Jamal Mashburn and Tayshaun Prince.

![]()

| Introduction | Why Basketball? Why Kentucky? Why Rupp? | Early Pioneers | The Game | Fall-out from the Game | Media Spin after the Game | Motivations for Perpetuating the Charge | Poor Journalism | The Evidence Against Rupp | Player Case Studies | The Evidence for Rupp | Reading List |

![]()

Adolph Rupp was a coach over a span of time when the society in America made dramatic changes.

In the spring of 1966 the nation was about midway between the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. It had watched Watts burn and witnessed the backlash against integration in Mississippi and elsewhere. - by Pat Forde, USA Today, "Legacy of Rupp Slow to Recede Repercussions of 1966 Title Game Still Echo in Many Ears," April 2, 1996.

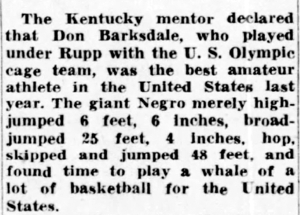

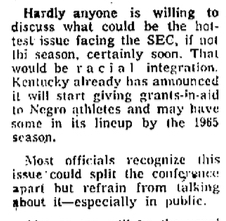

Many basketball teams in the South did not have black players on their rosters or admit black students into their institutions. The Southeastern Conference especially had many member schools so opposed to integration that some schools refused to compete against other schools with black players. Mississippi State at one time had to sneak out of town under the cover of darkness to play in the NCAA Tournament. (This, after ignoring bids in earlier years.)

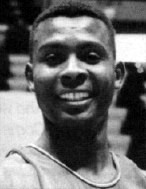

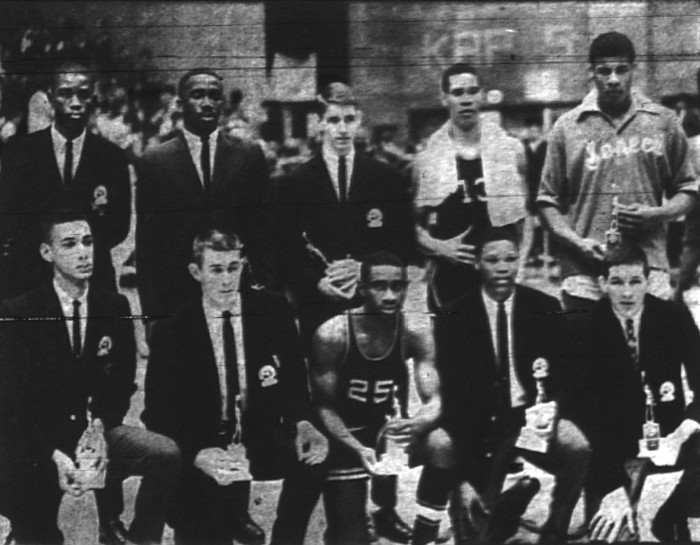

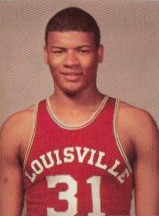

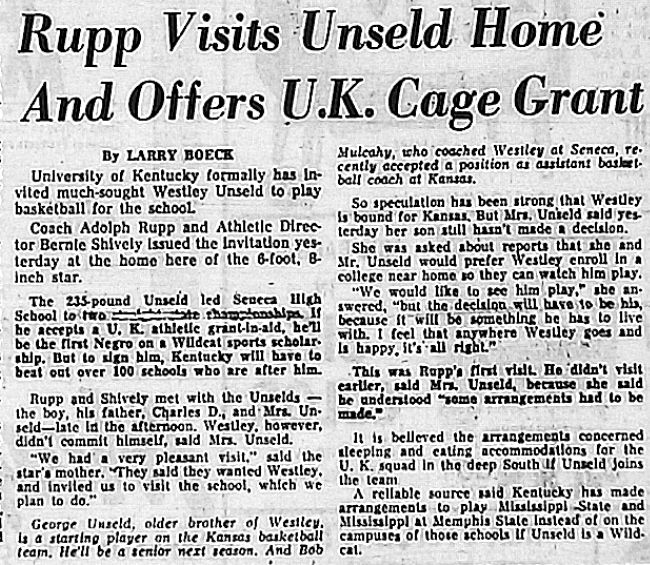

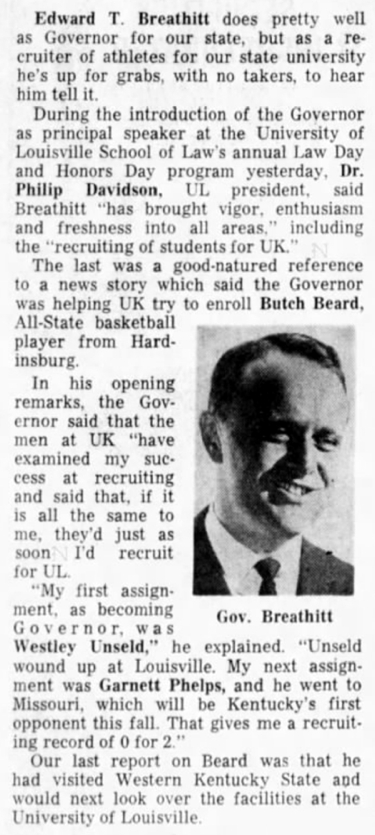

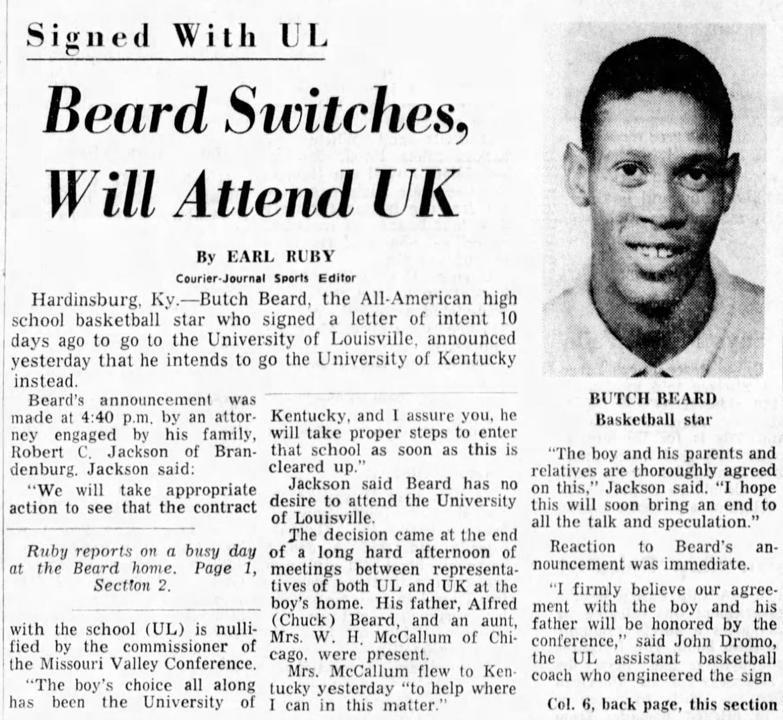

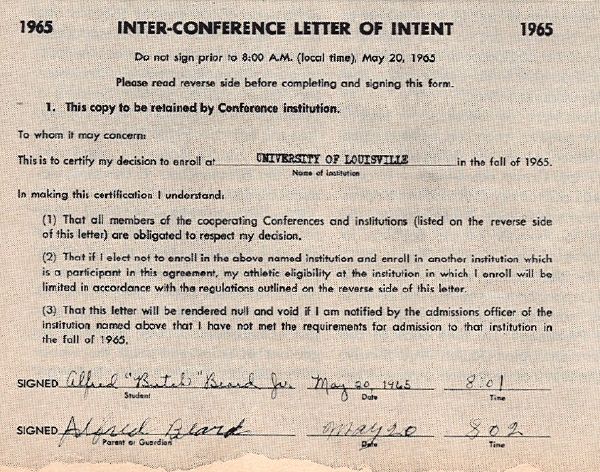

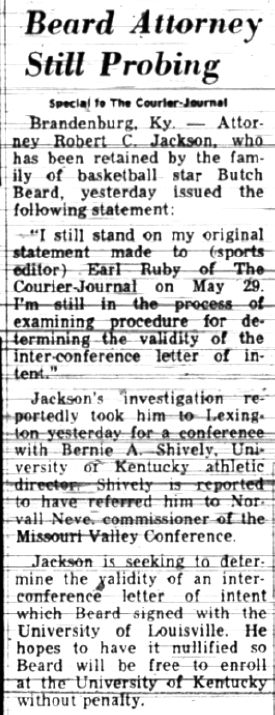

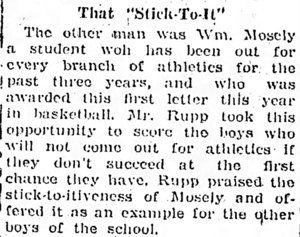

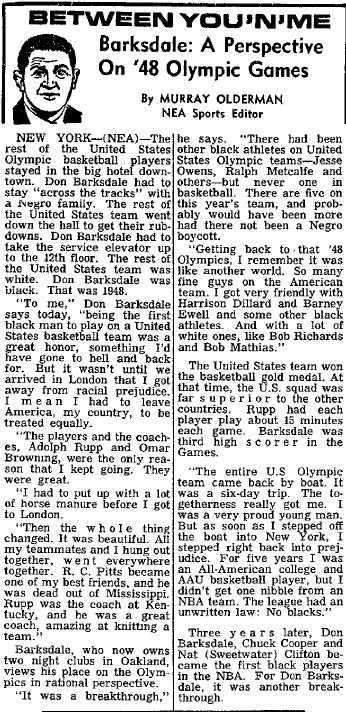

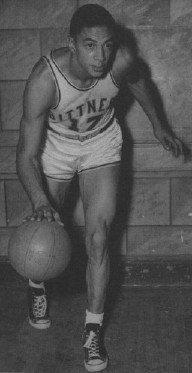

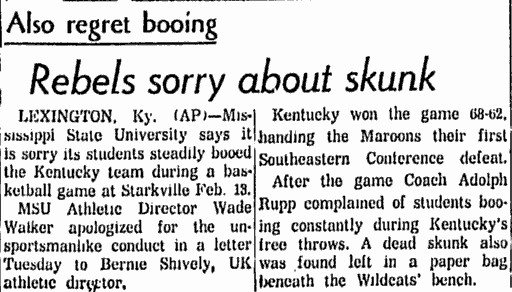

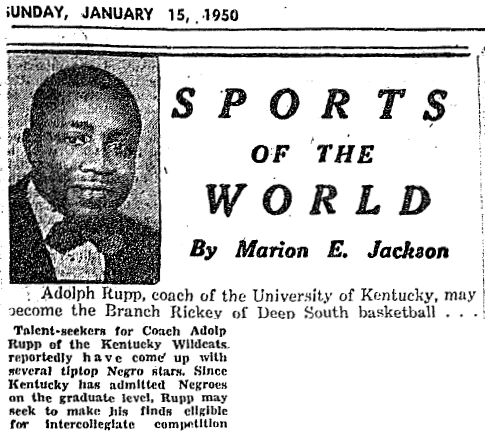

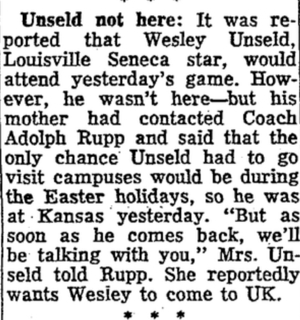

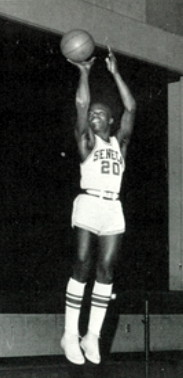

During that time, Rupp was playing all comers around the country, white or black. He often took his team to Chicago or New York to play against some of the powerhouse collegiate teams with black players. He recruited black players (at least fifteen - Lexington Herald Leader, March 31, 1990.), including Wes Unseld, Butch Beard and Jim McDaniels, but it was a difficult undertaking to convince a black player to come to Kentucky. Doing so, he would be the focal point in college basketball, as at that time Kentucky was the premier basketball dynasty. A black player would be subjected to the worst taunts and slurs imaginable during road games at places such as Oxford and Starkville Mississippi, Athens Georgia, Baton Rouge Louisiana etc. (Not to mention the aspect of arranging lodging and meals in the segregated South.) Nevertheless, there were a number of people who claimed that Rupp did not recruit these players or when he did, Rupp didn't recruit them hard enough.

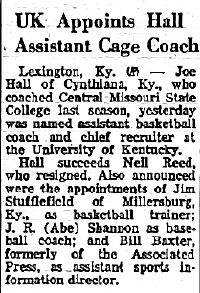

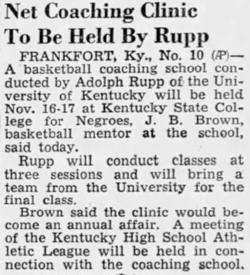

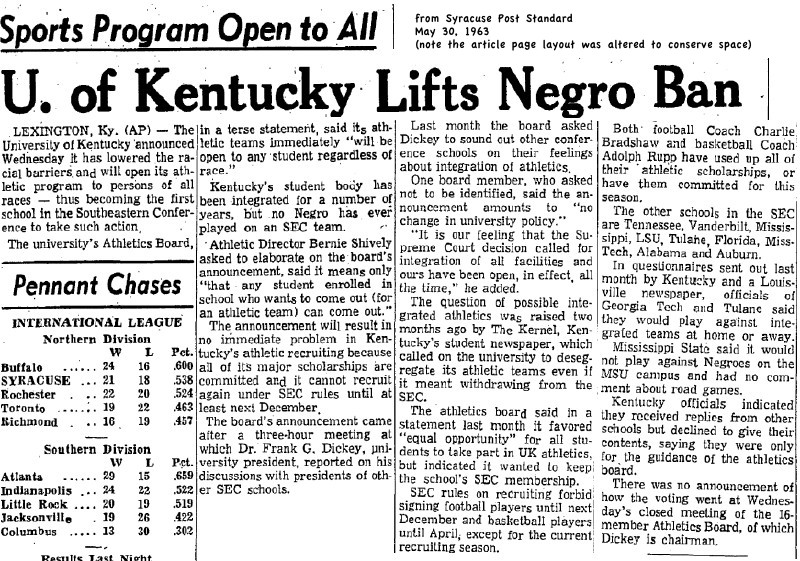

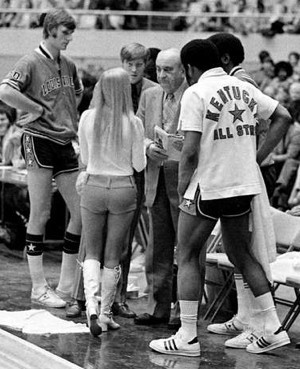

When Rupp finally did sign Tom Payne in 1969, Kentucky was one of the early SEC schools (starting with Vanderbilt with Perry Wallace, followed by Auburn with Henry Harris, Alabama with Wendell Hudson) to sign a black player (*). Football players Darryl Bishop and Elmore Stephens joined the UK team in the 1971-72 season for a short time, Rupp's last season as coach. (by John McGill, Lexington Herald Leader, "Kentucky a Leader in Integrating SEC Sports," March 31, 1990.)

It is difficult to assess the attitude of a man who is long since dead, especially the Baron who was only well known by those few close to him. A large amount of anecdotal evidence suggests that Rupp showed few signs of being racist and in fact supported blacks while a few specific quotes attributed to him suggest he was indeed racist. So was Rupp racist or not? The information at hand is too contradictory to say for certain. Most likely he was to an extent, just as the majority of white men his age living in the South at the time would be judged racist by today's standards. There are two explicit instances where Rupp, while angry, made derogatory comments about blacks to people in confidence. Was he overtly racist? The evidence does not show any public statements or acts to suggest so.

"To put 1997 standards on Coach Rupp during the time that he coached -- in the 1930s, 40s, 50s, 60s and a couple of years in the 70s -- is totally unfair." - C.M. Newton, CNNSI, "New Era in Lexington," October 30, 1997.

"I know there have been a lot of people who thought he was a racist. But I think the times can dictate how people act -- where you're brought up, how you're brought up. If he was a racist, he wasn't alone in this country. I'm never going to judge anybody. . . . That's a long time ago, too . . . You learn from the past, and you go on." - Orlando "Tubby" Smith, Chicago Tribune, "New Face Leads Kentucky These Days," November 30, 1997.

The following information is intended to present the evidence at hand, both pro and con, so people can make an informed decision for themselves. Granted, much of the information is contradictory but that's what can happen when you try to understand a real person rather than a stereotype.

Warning and Note - This page is an extremely long and often rambling piece. If you are pressed for time and are only interested in the topic of Adolph Rupp and the evidence of whether he was racist or not, I would suggest you read the evidence against Rupp and the evidence for Rupp sections. If you are interested in the history of the championship game and its ramifications, I would suggest you read the game, fall-out from the game and media spin after the game sections. If you are interested in stories of some of the black pioneers who integrated basketball in the south, I would suggest you read the early pioneers and the player case studies sections.

Despite what some may assume, the major point of this entire page revolves around the media and how they have done a poor job reporting and discussing this topic. If you are interested in how the media has distorted and shaped this topic through the years, please be sure to read the media spin after the game, motivations for perpetuating the charge and examples of poor journalism

Please note that the page itself contains links to numerous other pages, photographs, reprints of newspaper articles etc. There are a few companion pieces to this page that are referred to on this page and which are linked directly below.

Return to top

![]()

Why Basketball? Why Kentucky? Why Rupp?

Why Basketball?

It may be useful to consider why it became an important issue that Adolph Rupp integrate his teams. Sports has always been an important tool in bringing together people of different races, economic levels, educational levels and interests. Basketball in particular was a high-profile sport where the players are easily recognizable (in comparison to football for instance) and work together closely as one unit.

"I think that in terms of race relations, athletics in general have contributed immeasurably to reducing tensions and putting people on a common ground." - William Winter on the impact of integrated athletics on the South, by Ed Hinton, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Run for Respect," September 7, 1986.

Many recognized that integrating sports teams was a quick way to gain acceptance and to bring about integration throughout society. Adolph Rupp was not the best example when it comes to integration, but he is also certainly not the worst. Perhaps people hoped UK would start signing black players so that other, more conservative schools could have the "excuse" to integrate their team (and in effect university) under the pretext of being able to compete.

Why Kentucky?

History shows that, while there were other factors, not until after Kentucky and Vanderbilt, in particular, began to integrate their track, football and basketball teams did other Southeastern Conference teams follow suit. The Southeastern, Southwest and Atlantic Coast Conferences were lagging behind the rest of the country when it came to integration in the 1960's. Kentucky was a entrance-way into breaking down the more conservative schools to its south. As a border state, Kentucky often had more in common with its midwestern neighbors to the north, Ohio, Illinois and Indiana than with states like Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana.

"'With the location and the circumstances that existed in the high school programs [already integrated], it was only natural that the University of Kentucky would initiate it [integration],' says Charley Bradshaw, the former Kentucky coach who signed the SEC's first black players" - by Ed Hinton, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Run for Respect," September 7, 1986.

Secondly, the population of Kentucky was more diverse. While a large part of the state was rural, there was also a large midwestern influence in cities such as Louisville and Lexington. The result being that the political climate was more moderate than might be found further in the south. (Kentucky, after all, was not even part of the confederacy during the Civil War.)

The fact that the University of Kentucky basketball team was the preeminent basketball program at the time made it a prime target for those looking to break down barriers. For one, Kentucky was a high-profile team which travelled around the country and earned media attention. To many in the North, Kentucky basketball was the South, simply because none of Kentucky's neighbors had the desire to travel (due in part because many didn't want to play against integrated teams but most likely also because not enough support or interest was given to basketball at these other schools to allow them to travel any substantial distances) to such places as New York City or Chicago. Therefore, Kentucky received the lions share of the scrutiny for why Southern schools were using all-white teams. Secondly, because of Kentucky's stature, it was felt that integrating the squad would have dramatic effects on the rest of the league. Having the hated UK come to town with black players could only hasten the rest of the league into recruiting their own. Ideally, coaches and athletic directors could tell their boosters and fans that "UK is signing blacks, we have to do the same or we'll never win."

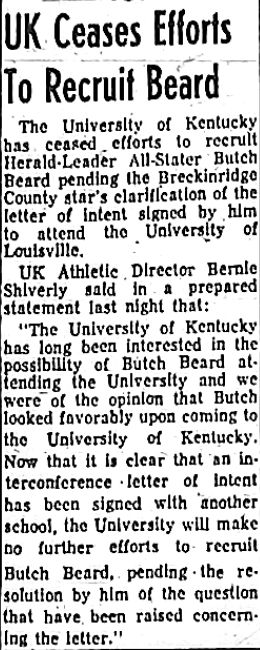

"Kentucky's pursuit of [Butch] Beard means that the SEC has a new gentleman's agreement to forget the old one [to not recruit blacks] and thus the last major-conference color bar has quietly fallen. This does not mean that every southern school is out chasing Negro athletes. But the pressure on those that are holding out for sporting segregation is likely to become irresistible as soon as they are regularly whupped by their integrated neighbors" - by Frank Deford, Sports Illustrated, "The Negro Athlete is Invited Home," June 14, 1965, pp. 26-27.

The hypothesis that people, both inside and outside UK, wanted UK to integrate its teams because that would mean more rapid integration throughout the South is supported by this item from Butch Beard's recruitment.

"Practically every day his senior year, Beard said, 'some Kentucky alum' came by his home. 'They wanted Kentucky to be the first to integrate the SEC. They said if Adolph did it, everybody would.'" - by Dave Kindred, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Facts Belie Stereotype of Racist Rupp at UK," May 11, 1997.

Why Rupp?

There are a number of reasons behind the eventual denunciation of Rupp, and in some ways it may seem inevitable. Rupp came from the obscurity of the Kansas plain, the son of hard-working Mennonite German immigrants. He went on to not only build a basketball dynasty where none had existed before but to play a hand in the shaping of the modern game. He was brash and arrogant when it came to his coaching ability and didn't mince words. His domination over teams in his own conference can only be described as ruthless. Rupp not only demolished his SEC foes, he didn't hide his disdain for these schools who put all their emphasis on football.

The coaches at both schools [Georgia Tech and Georgia] still taught physical education classes, or were football assistants filling in between seasons; they got a bonus for taking on basketball. It was a practice so obsolete the Adolph Rupp was insulted that his Kentucky teams had to play them." - by Furman Bisher, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Oh, If Adolph Rupp Could See the Football State Now," February 10, 1985.

"Because the other schools were unwilling to make such a commitment to a sport [basketball] that couldn't show a profit, the SEC was so weak as a league that Kentucky had to depend on non-conference games for quality competition. Rupp, not known for subtlety, told the rest of the SEC it had better improve or 'we'll bury you.'" - by Tony Barnhart, The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Basketball Revolution Comes to the South: Once the Stepchild of Most Athletic Programs,: The Game has Taken Hold in the SEC, Thanks to Integration . . .: and an Old Man in a Brown Suit," November 22, 1987.

|

"I know I have plenty of enemies," he [Rupp] once said, "but I'd rather be the most hated winning coach in the country than the most popular losing one." - by Joe Gergen, Sporting News Final Four Archive, "1951, Kentucky is Top 'Cat Again."

"Defeat and failure to me are enemies. Without victory, basketball has little meaning. I would not give one iota to make the trip from the cradle to the grave unless I could live in a competitive world." Adolph Rupp after gaining his fourth NCAA title, - by Jim Savage, The Encyclopedia of the NCAA Basketball Tournament, Dell Publishing, 1990, pg. 705.

Rupp was also obsessed with not only winning but with perfection from his teams.

Once the Fabulous Five ran up a 38-4 halftime lead, but Rupp was furious - a single player had scored all the opponent's points, and the Baron wanted him stopped. "Somebody guard that man," Rupp bellowed. "Why, he's running wild !" - by Jim Savage, The Encyclopedia of the NCAA Basketball Tournament, Dell Publishing, 1990, pg. 706.

When asked to compare his current 50-51 team which went on to win a national championship to the Fabulous Five team of 47-48, Rupp said, "They [the Fabulous Five] liked to crush everybody early and get it over with. This bunch is tender-hearted - the only one they're killing is me." - by Associated Press, "Rupp Says Fletcher Caused Most Trouble," Lexington Herald, March 25, 1951.

While Rupp enjoyed the limelight, media relations or sensitivity was not his strong suit. It seems apparent that Rupp was consumed with coaching basketball and was mostly likely oblivious to most other things in life, including civil rights.

"He (Rupp) probably misjudged the power and impact and rightness of the civil-rights movement because, to tell the truth, Rupp never seemed interested in much except himself and basketball." - by Billy Read, Lexington Herald Leader, March 1997.

"I concede one thing to Sports Illustrated and George Will. Rupp probably never cared that his teams had no black players. All that mattered to him was winning and he won without them," - by Dave Kindred, Lexington Herald Leader, "Calling Rupp a Racist Just Doesn't Ring True," December 22, 1991.

It should also be noted that Rupp's personality wasn't the most sociable, off the court or on, and this has hurt him in the eyes of history.

"Rupp was unique," said Bill Spivey, a Kentucky star in the 1950s. "He wanted everybody to hate him and he succeeded. He called us names some of us had never heard before." - by Dave Kindred, Atlanta Journal and Constitution "The Baron Made Basketball Important," March 16, 1997.

"Adolph would never allow himself to get close to the players," [former player Tommy] Kron said. "He was a tough, gruff kind of guy who would verbally abuse his players to get them to play harder." by Jo-Ann Barnas, Detroit Free Press, "They Changed the Game: Texas Western," March 29, 1996.

Harry Lancaster relates one of Rupp's favorite jokes about himself.

While he [Rupp] was still coaching he liked to tell the story about a coach in the Southeastern Conference who had heard that Adolph was dead. The coach went to his athletic director to get funds to make the trip to Lexington for the funeral. "What a nice gesture," the athletic director told him "What a nice thing to do to pay honor to Coach Rupp." "Honor hell," the coach shouted, "I want to go up there just to make damn sure he's in that box." - by Harry Lancaster, Adolph Rupp As I Knew Him, Lexington Productions, 1979, pg. 119

Return to top

![]()

Sidebar: The Kentucky Day Law The Kentucky Day Law was proposed by state Representative Carl Day of Breathitt County. It was signed into law March 1904, and took effect in July 1904. The intention of the law was to prohibit black and white students from attending the same school. In addition, black students were not allowed to attend schools located less than 25-miles from a whites-only school. This law was aimed directly at Berea College, which had begun to co-educate blacks and whites together. The law's passing resulted in a lawsuit between Berea and the Commonwealth of Kentucky that made it to the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1908, the Justices upheld the Law when they determined to extend the 1896 opinion of Plessy versus Ferguson to include state institutions of higher learning. This was later overturned as part of the Brown versus Board of Education, Topeka ruling in 1954.

|

|

In 1954, the undergraduate school was opened to blacks and twenty enrolled. (Lexington Herald Leader, "History of Blacks in Lexington," February 21, 1988.) This occurred after the United State Supreme Court in June 1954 struck down the Day Law as part of the famous "Brown vs. Board of Education" ruling and mandated that integration occur "with all deliberate speed." The decision was met with approval from Kentucky's governor, Lawrence Wetherby, state senators Earle Clements and John Sherman Cooper, all of whom expressed their support of the ruling.

In 1965, Joseph Walter Scott joined the sociology department and became the first black full-time faculty member at the University. (Lexington Herald Leader, "'49 Lawsuit Started UK on Path to Diversity," April 14, 1996.)

One important factor that should not be overlooked when considering integration of athletics in the South was the timing of passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which president Lyndon Johnson signed in law on July 2, 1964.

The heart of the law dealt with public accommodations, saying that blacks no longer could be excluded from restaurants, hotels and other public facilities. For an integrated athletic team travelling in the South, these were exactly the types of accommodations relied upon during such a road trip. This law didn't change practices in the South overnight, but it did give those who were willing to defy segregation the power of courts and in theory the federal government behind them. Prior to this time, defying segregation was an extremely dangerous proposition (not that it wasn't even after the law went into effect.) This reality is one which some critics in the past have either underestimated or overlooked completely.

|

Athletics - Basketball

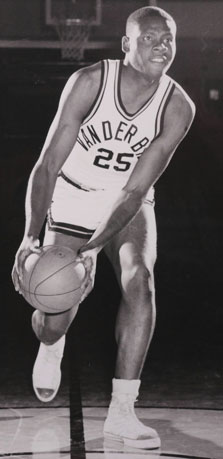

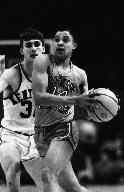

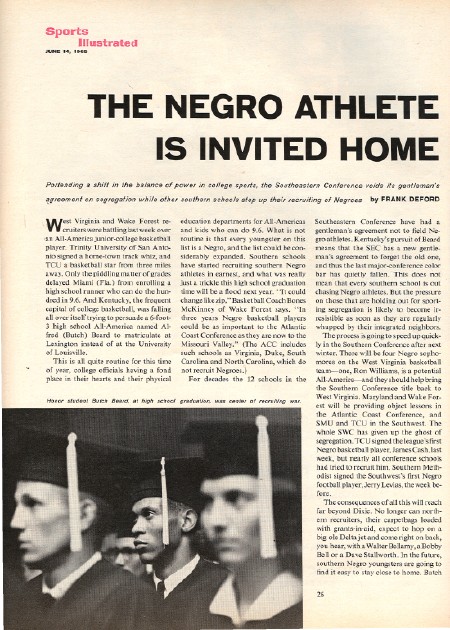

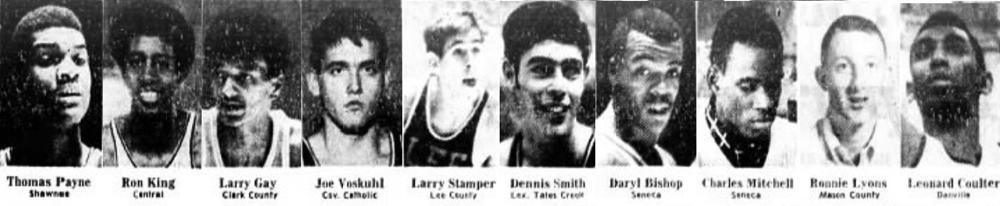

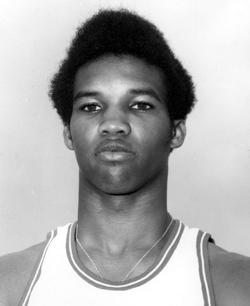

The first black basketball player in the SEC was Perry Wallace (from Nashville and valedictorian of his senior class at all-black Pearl High School) at Vanderbilt, who was also recruited by Kentucky.

"He [Wallace] had been the ideal candidate for the Grand Experiment. He was a class valedictorian who would have no trouble getting through school. He came from a stable family, he was well-spoken, a Nashville native and a local son; Wallace's presence put a lot of pressure on Vanderbilt to recruit him. A couple of other SEC teams talked to him, all to Wallace's surprise. He had had no intention of becoming a pioneer." - by Los Angeles Times Service, Reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, "In the South, Blacks were Pioneers on Sports Frontier," March 21, 1983.

|

"I saw athletes, particularly black athletes, who were illiterate," he said. "I saw seniors who hadn't grown culturally. I called these schools the new plantation. I was scared away, even though they were in the North, the land of the exodus." - by Los Angeles Times Service, Reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, "In the South, Blacks were Pioneers on Sports Frontier," March 21, 1983.

Pressure from the local community and a desire to break stereotypes led him to make his decision to break the SEC color barrier in basketball.

"I wanted to be an example of what black people could produce," he said. I wanted to show that we weren't just colored people on the wrong side of the track, who hadn't developed good values, who weren't intelligent or productive. . . I was always conscious of not reinforcing the negative images of black players," he said. "It inhibited me . . . I played a cautious, conservative game." - by Los Angeles Times Service, Reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, "In the South, Blacks were Pioneers on Sports Frontier," March 21, 1983.

With Wallace on the freshman team was Godfrey Dillard (from Detroit, MI). The two had to put up with opposing fans who "shouted racist slogans, spat at them, threw soft drinks and even threatened to lynch the two young strangers in black and gold trunks." (Joseph Stroud, Lexington Herald Leader, "Breaking the Color Barrier," March 1 1992.) (JPS Note: Here is an article which interviews Wallace during his freshman year.)

When Wallace would go on the road with Vanderbilt, especially at Mississippi or Auburn, the fans would call him every racial name imaginable. They would threaten to castrate him. In some places, it was said, cheerleaders would lead racial cheers against him. School officials, meanwhile, sat silent. Wallace said he was concerned for his life at times. He figured he could be shot. "This was the South," he said. "At that time in the South, a time of social upheaval, anything could happen." - by Los Angeles Times Service, Reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, "In the South, Blacks were Pioneers on Sports Frontier," March 21, 1983.

"It was just a chilling, scary situation. The trips to the south, the crowd was just awful, calling you all kinds of names, all kinds of racial epitaphs. They threatened you, and they hoped above all that you would fail." - Perry Wallace, "Glory in Black and White," CBS, April 2002.

|

After injuring his knee and becoming involved with the campus "Afro-American Society" and local and campus politics, Dillard was unceremoniously dropped from the team and never got to play varsity basketball for Vanderbilt. Wallace went on to be named captain and earn second team All-SEC honors as a senior but his journey was anything but easy.

"I almost had a nervous breakdown," he [Wallace] said of his college days. "They weren't the worst four years any black person had ever encountered, but they were difficult years. I had to figure out how I was going to deal with the pain, the confusion. It took some time." - by Los Angeles Times Service, Reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, "In the South, Blacks were Pioneers on Sports Frontier," March 21, 1983.

"Would I ever do it again?" wonders Wallace. "I don't know. Probably not. But a son of mine? God, no. Never. I'd never put him through something like that." - by Los Angeles Times Service, Reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, "In the South, Blacks were Pioneers on Sports Frontier," March 21, 1983.

The fate of many of these pioneers was tragic.

Henry Harris, the first Auburn player, jumped off a New York (sic, actually Milwaukee) building and killed himself a few years later. Tom Payne, the first at Kentucky, is in a California prison on his fourth rape conviction. Both Wallace and Dillard say they know why. "In some ways, being in that position puts you on a fence, where you fall on one side or the other," Wallace said. "And that was clear to me -- it was clear which side I need to fall on. And I had to fight to do it and to find the strength to do it." - by Joseph Stroud, Lexington Herald Leader, "Breaking the Color Barrier," March 1 1992.

The fourth black player in the SEC was Wendell Hudson at Alabama in 1969. He described his experience as "It was a difficult experience, at times, but a positive one," said Hudson, an assistant basketball coach at Rice. "I'm a better person for having done it. If I had to do it over again, I would, without a doubt." - by Los Angeles Times Service, Reprinted in Philadelphia Inquirer, "In the South, Blacks were Pioneers on Sports Frontier," March 21, 1983.

The Atlantic Coast Conference didn't get off to a rousing start either when beginning to admit black players in the early 1960s. One problem the ACC had was that in response to a point shaving scandal, the league 'voluntarily' increased their admission standards for scholarship athletes. This made it even more difficult to find a black athlete who was adept both on the basketball court and in the classroom. A great high school talent, Lou Hudson of all-black Dudley High School in North Carolina shunned the league and instead opted to enroll at Minnesota where he became an All-American for the Golden Gophers.

"The only ACC school that showed any interest in me was N.C. State," Hudson says. "They invited me to a game against Villanova in the Greensboro Coliseum. Villanova had a black player named Hubie White, and he drew jeers from the crowd....I never actually met Everett Case, but it was suggested that if I enrolled as a student, the booster club would cover my expenses. It seemed to me like a chicken way to operate. They obviously were covering their backs.... I figured, if you can't swim, why walk on thin ice? Times were beginning to change, but I came along a couple of years too early. They weren't ready for me, and I wasn't ready to be a pioneer under those conditions." - Lou Hudson by Larry Keech in Greensboro News & Record, "One March Night 30 Year Ago Changed the Face of Basketball Today," March 7, 1996.

Billy Jones was the first black varsity basketball player in the ACC, playing for the Maryland Terrapins in 1965-66. (Note that his teammate Julius "Pete" Johnson was in his same class but redshirted his sophomore season.) Jones related his experiences growing up in Maryland

"I'm the only one [of his black friends and teammates in Baltimore] who attended a major school. We would get tons of letters from college recruiters. The minute they found out you were black, the communication stopped."

"I remember playing lacrosse for Towson, and someone putting their stick in my groin with the intent to injure. We had an upset win in basketball at Dundalk. The crowd rocked our bus as we were trying to get off the parking lot." - by Paul McMullen, Baltimore Sun, "History in Black, White -- and Gray," December 10, 1999.

The transition to college for the black player was not as harsh as it was for the SEC pioneers, although there were still obstacles.

When Darryl Hill played for Maryland [in football] in 1963, there was speculation that Clemson and South Carolina, then a member, would pull out of the ACC, but both stayed. Brought in by Bud Millikan, Jones remembers the ovation he received when he entered his first ACC tournament game, at Reynolds Coliseum in Raleigh, N.C.

"Some basketball people appreciated what I was doing," Jones said. "You've got to remember, South Carolina had a bunch of players from New York, and they were used to dealing with people like me. I do remember one instance at South Carolina, when I was going for a ball rolling into the corner, and somebody in the stands called me [a racial epithet]."

"As much as possible, we [the team members] did things together, but [current Maryland coach] Gary Williams and the rest of the guys were welcome in places where I was not. You're captain of the basketball team as a senior, and you get no offers to join a fraternity? I understood. I wasn't even irritated."

All above quotes by Paul McMullen, Baltimore Sun, "History in Black, White -- and Gray," December 10, 1999.

JPS Note - It is interesting to note that Jones was in attendance at the championship game in Cole Field House. He was entertaining a recruit and was sitting a few rows behind the Kentucky bench.

|

"I wasn't hell-bent to be a pioneer in ACC basketball," Claiborne says now. "Deep down, I still probably would have preferred to play at (North Carolina) A & T. But that would have been a selfish decision on my part. Going to a school with Duke's academic reputation and playing in the ACC were the kinds of opportunities that raised the expectations of the (black) community in a small town like Danville." - C.B. Claiborne by Larry Keech in Greensboro News & Record, "One March Night 30 Year Ago Changed the Face of Basketball Today," March 7, 1996.

Claiborne still encountered racial problems during his stay at Duke, both on and off the court.

"I can remember hearing racial slurs and seeing Confederate flags when we played against Alabama in Tuscaloosa, Ala.," Claiborne says. "When I went to the foul line, I gritted my teeth and told myself, 'If I never make another free throw, I'm going to make this one.'"

"I could sense that there was a group of (Duke) alumni who didn't want me involved," he says. "They would never say anything to my face. But you can read some things from body language, like a certain kind of expression or when somebody turns their back on you...I can remember not being invited to a team awards banquet at Hope Valley Country Club because it was segregated." - C.B. Claiborne by Larry Keech in Greensboro News & Record, "One March Night 30 Year Ago Changed the Face of Basketball Today," March 7, 1996.

Below is a listing of the first black athletes to play basketball in ACC, SEC and the old Southwest Conference schools.

JPS Note - Some will attempt to claim that because one school signed players a few years before another that this makes one school morally superior than the other. I personally tend to think that all the schools were lagging and this listing indicts every single school.

| School | Initial Varsity Season* | Player | Career Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Houston | 65-66 | Don Chaney Elvin Hayes | Chaney, an All-America as a senior, averaged 12.6 ppg in three seasons and was a member of the Final Four teams in 1967 and 1968. Hayes, a three-time All America, averaged 31 ppg and 17.2 rpg in three seasons. The Hall of Famer led the Cougars in scoring and rebounding all three years. |

| Maryland | 65-66 | Billy Jones | Averaged 8.9 ppg and 4.5 rpg in three seasons. He was the Terrapins' third-leading scorer and rebounder as both a junior and senior. |

| Duke | 66-67 | C.B. Claiborne | Averaged 4.1 ppg in three seasons |

| Texas Christian | 66-67 | James Cash | Averaged 13.9 ppg and 11.6 rpg in three seasons. All-SWC selection as a senior when he led the Horned Frogs in scoring (16.3 ppg) and rebounding (11.6 rpg). He had six games with at least 20 rebounds. |

| Baylor | 67-68 | Tommy Bowman | Led the Bears in scoring (13.5 ppg) and rebounding (9.4 rpg) in his first varsity season. All-Southwest Conference choice in '67-68 and '68-69. |

| North Carolina | 67-68 | Charlie Scott | Averaged 22.1 ppg and 7.1 rpg in three seasons. He was a consensus second-team All-America choice in his last two years. |

| Vanderbilt | 67-68 | Perry Wallace | Averaged 12.9 ppg and 11.5 rpg in three varsity seasons. He was the Commodores' leading rebounder as a junior (10.2 rpg) and leading scorer as a senior (13.4 ppg). |

| Wake Forest | 67-68 | Norwood Todmann | Averaged 10.5 ppg and 4.1 rpg in three seasons, including 13.3 ppg as a sophomore. |

| Arkansas | 68-69 | Thomas Johnson | Averaged 15.5 ppg for 1967-68 freshman squad |

| North Carolina State | 68-69 | Al Heartley | Averaged 4.8 ppg in three seasons. |

| Texas | 68-69 | Sam Bradley | Averaged 6.5 ppg in his only varsity season. |

| Auburn | 69-70 | Henry Harris | Averaged 11.8 ppg, 6.7 rpg and 2.5 apg in three-year varsity career. Standout defensive player was captain of Auburn's team as a senior. |

| Rice | 69-70 | Leroy Marion | Averaged 5.6 ppg and 3.3 rpg in a three-year varsity career marred by a knee injury. |

| Texas Tech | 69-70 | Gene Knolle Greg Lowery | Knolle, a two-time All-SWC selection, averaged 21.5 ppg and 8.4 rpg in two seasons. Lowery, who averaged 19.7 ppg in his three-year career, was first-team All-SWC as a sophomore and senior and a second-team choice as a junior en route to finishing as the school's career scoring leader (1476 points). |

| Alabama | 70-71 | Wendell Hudson | Averaged 19.2 ppg and 12 rpg in his career, finishing as Alabama's fourth-leading scorer and second-leading rebounder. The two-time first-team All-SEC selection was a Helms All-America choice as a senior in 1972-73. |

| Clemson | 70-71 | Craig Mobley | Played sparingly in his only season. |

| Georgia | 70-71 | Ronnie Hogue | Finished three-year varsity career as the second-leading scorer in school history (17.8 ppg). He was an All-SEC choice with 20.5 ppg as a junior, when he set the school single-game scoring record with 46 points vs. LSU. |

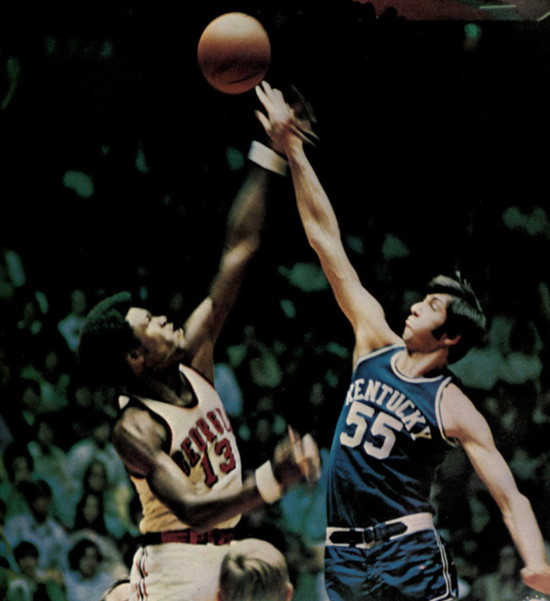

| Kentucky | 70-71 | Tom Payne | Led the Wildcats in rebounding (10.1 rpg) and was their second-leading scorer (16.9 ppg) in his only varsity season before turing pro. He had a 39-point, 19-rebound performance vs. LSU |

| South Carolina | 70-71 | Casey Manning | Averaged 2.6 ppg and 1.8 rpg in three seasons. |

| Florida | 71-72 | Malcolm Weeks Steve Williams | Meeks played sparingly in two seasons. Williams, who averaged 8 ppg and 5.2 rpg in three varsity seasons, was the Gators' second-leading scorer as a sophomore (12.8 ppg). |

| Georgia Tech | 71-72 | Karl Binns | He was the leading rebounder (6.5 rpg) and fourth-leading scorer (8.8 ppg) in his only season with the Yellow Jackets. |

| Louisiana State | 71-72 | Collis Temple | Averaged 10.1 ppg and 8.1 rpg in three seasons. Ranked second in the SEC in rebounding (11.1 rpg) and seventh in field-goal shooting (54.9%) as a senior. |

| Mississippi | 71-72 | Coolidge Ball | Two-time All-SEC selection (sophomore and junior years) averaged 14.1 ppg and 9.9 rpg in three seasons. He led the Rebels in scoring (16.8 ppg) and was second in rebounding (10.3 rpg) as a sophomore. |

| Tennessee | 71-72 | Larry Robinson | Averaged 10.9 ppg and 8.8 rpg in two seasons. Led the Volunteers in rebounding and field-goal shooting both years. |

| Texas A & M | 71-72 | Mario Brown | Averaged 13 ppg and 4.3 apg in two seasons, leading the team in assists both years. |

| Virginia | 71-72 | Al Drummond | Averaged 5.2 ppg in three varsity seasons. |

| Mississippi State | 72-73 | Larry Fry Jerry Jenkins | Fry averaged 13.8 ppg and 8.1 rpg in three seasons. Jenkins, an All-SEC selection as a junior and senior when he was the Bulldogs' leading scorer each year, averaged 19.3 ppg and 7 rpg in three seasons. |

* - Note that during this era freshmen were ineligible for varsity. This table only lists the first black player at the respective schools to play varsity. There were some cases where black players participated on freshmen teams but did not end up playing varsity, for various reasons, and subsequently are not listed above. In addition in not all cases did these players receive a scholarship from the school. | |||

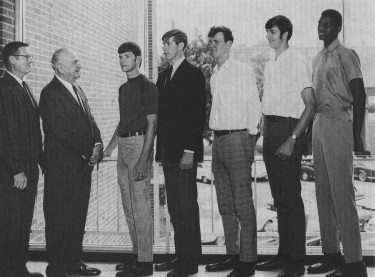

Athletics - Football

The first black athlete to receive a grant-in-aid and play varsity for a SEC school was Nat Northington (from Thomas Jefferson High School in Louisville) for the University of Kentucky football team in the fall of 1967. (Lexington Herald Leader "History of Blacks in Lexington," February 21, 1988). Greg Page (from Middlesboro, KY) was also on the team and was awarded a scholarship. (Letter to the Editor, by Edward Breathitt, Chairman, Board of Trustees, University of Kentucky, Lexington Herald Leader "New Coach Fits Well with Kentucky Goals and Legacy," May 13, 1997.) Jim Green was also signed by Kentucky to join the Wildcat track team.

The New York Times, December 20, 1965 pg. 56. LEXINGTON, Ky., Dec. 19 (AP) - For the first time the University of Kentucky has given an athletic grant-in-aid to a Negro. He is Nat Northington, a star back and an "A" student at Thomas Jefferson high School in Louisville. The university president, John Oswald, said today: "Northington is an outstanding young man who will be a great credit to the university and its football program." Kentucky had tried unsuccessfully for two years to sign Negroes to grants-in-aid, including two basketball players and a football player who went elsewhere. |

"By August 1967, indications were strong that the historic role of the first black to participate in a Southeastern Conference football game would belong to Greg Page, defensive end. He was outgoing, talented, and by preseason practice that year was listed on the depth chart second only to the team leader, starting defensive end Jeff Van Note, who would spend 18 years with the Atlanta Falcons. Then came the 'pursuit drill' . . . Greg Page got to the ball-carrier first. Piling in behind Page came every other defensive player. . . . When the play was over, Greg Page lay on the ground. 'We knew he was hurt,' says Van Note, . . .'but not how badly he was hurt.'" - by Ed Hinton, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Run for Respect," September 7, 1986.

|

After much soul searching themselves, the freshman stuck it out to play the next year on the varsity. The decision was not an easy one though. "When Hackett went home, his friends and neighbors admonished him: 'They killed Greg up there [Lexington], man. What are you doing still up there?'. After thinking it over, Hackett and Hogg followed Northington's advice to stick it out. "We decided to stay," says Hackett. "And it was rough."

(All above quotes from "Run for Respect," by Ed Hinton, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, September 7, 1986.)

|

"Yeah, Daddy, he's still quite a UK fan. He's still very, very active. He follows them everywhere. In fact, he was in New York when they won their national championship [in 1996]. He retired from GE, I think about eight or 10 years ago, and now his life is his grandkids and his kids and UK. And I mean he is one of those born-again UK fans." Wilbur Hackett Jr., by John Filiatreau, Louisville Magazine Web Edition, "Boys of Summer," April 1997.

Along with Hackett, Houston Hogg (Daviess County) and Albert Johnson (Thomas Jefferson, Louisville) made up the black recruiting class that year. The decision to come to UK was still a big step filled with potential dangers, real and imagined.

"There were a lot of things said about it, by family and friends alike," recalls Hackett's mother Olive. "But all the schools were having problems with race at that time. Everybody always mentioned Adolph Rupp, but to me, there was an Adolph Rupp at every school." - by John Filiatreau, Louisville Magazine Web Edition, "Boys of Summer," April 1997.

After the injury to Page and the loss of Northington (and Johnson who got injured and also left), Hogg and Hackett went on to face the SEC alone. [No team in the SEC had a black player at the time save Tennessee with one (Lester McClain).]

"I had some very tough times. I mean, you're talking about George Wallace standing in front of the doors at the University of Alabama. You're talking about going to Mississippi for the first time as a 17- or 18-year old kid, traveling the South. This was at the time of the Freedom Riders. You're talking about racial strife that really intensified; you're talking about the riots. I had some incidents, racial incidents, that I will always remember. But overall, I enjoyed it. UK was good to me. I met a lot of good people there; I still have good contacts with people at UK. If I have something that I regret, it's that I never managed to finish my degree." - by John Filiatreau, Louisville Magazine Web Edition, "Boys of Summer," April 1997.

Hackett carved out a respectable collegiate career, despite playing on outmanned UK football teams. His junior year, he was elected captain of the team, making him to first black to be so recognized on an SEC team, an honor which was repeated his senior season.

"I had a good junior year, made honorable mention All-SEC, and after that we started to get more blacks," Hackett says. "We recruited about six guys from Louisville, and things began to change." - by John Filiatreau, Louisville Magazine Web Edition, "Boys of Summer," April 1997.

|

|

Reaction by some coaches included Georgia Tech football coach Bobby Dodd who said "I am not surprised. Since it has been rumored that Kentucky will have a Negro basketball player soon. I am not surprised that they have a Negro player out for football." Said Vanderbilt football coach Jack Green: "That's their business. If they bring him down here we'll play them. We'll go up there and play them. We've played schols in the past with Negro athletes. If a school wants to play a Negro athlete that's their business. We have no objections." (quotes from "Negro is Among 71 UK Hopefuls," by Billy Thompson, Lexington Herald, late March 1964.)

JPS Note - The article did not interview football coaches from less urban schools like those in Alabama and Mississippi.

Matthews, who was fifth on the depth chart at fullback knew that he faced long odds at making the squad, especially since he admitted at the outset that he was not in great shape at the start of the training camp. He did not end up making the team, but he did achieve a Southeastern Conference milestone for his efforts.

Return to top

![]()

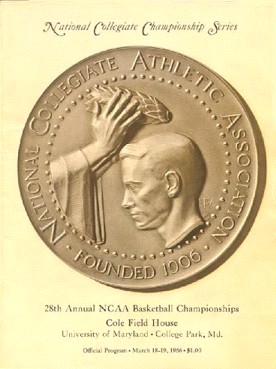

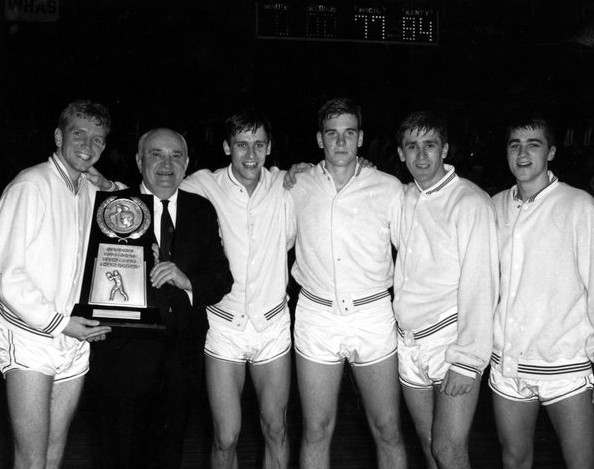

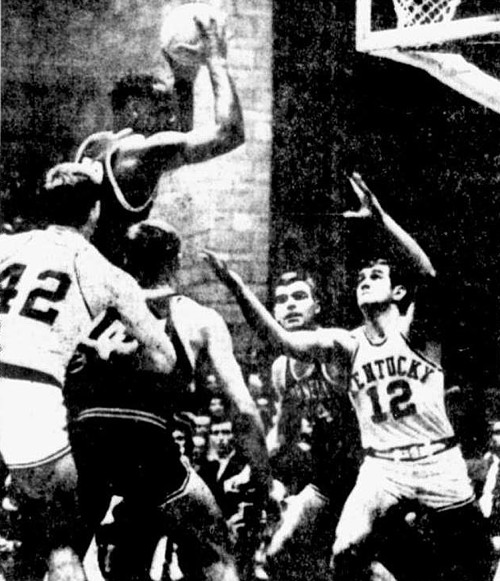

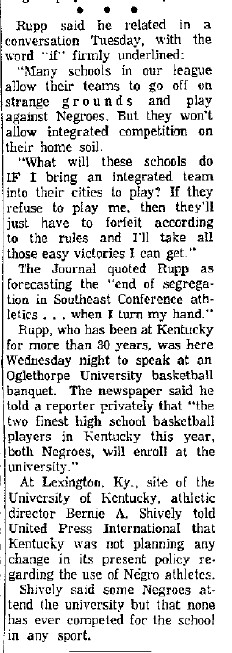

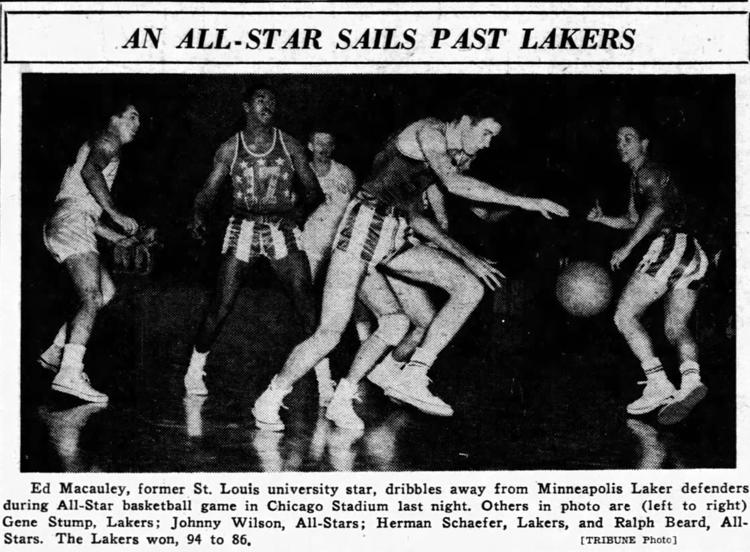

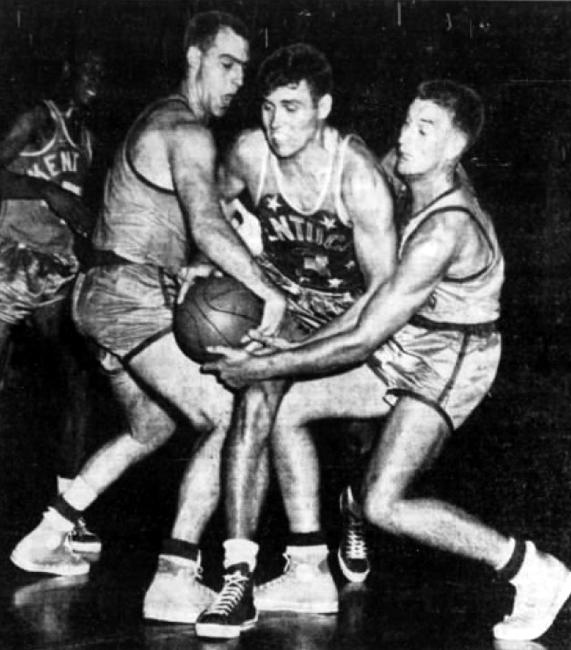

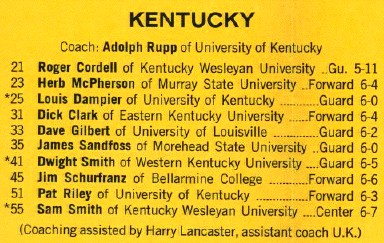

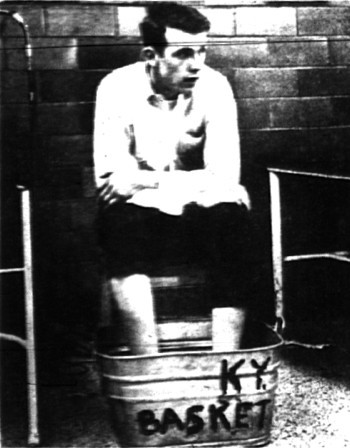

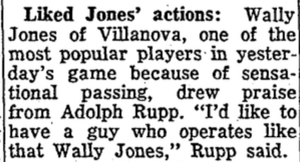

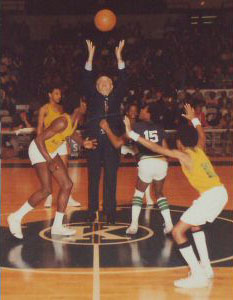

The game between Kentucky and Texas Western didn't hold the importance at the time that it received in later years. Western won 72-65 in what many concede was a sloppy ball-game. Kentucky, despite not having any starter taller than 6-5, steadily improved over the year and formed into a fine-tuned machine, relying on the shooting of their two stars Pat Riley and Louie Dampier. Kentucky was impressive during the tournament in dispatching Dayton 86-79 and the Cazzie Russell-led Michigan Wolverines 84-77. In the semifinals, Kentucky outlasted Duke 83-79, in a game where players from both sides were battling the flu. Texas Western came into the tournament with a 23-1 record and a ranking of #3 in both wire-service polls. Despite this, they were largely an unknown commodity to most of the nation, no doubt due in large part to their remote location in El Paso. They were led by a young Don Haskins, who ground into his team a strong dedication to tough defense. Their road to the final four was rocky, surviving an overtime victory over Cincinnati and a double overtime contest with Kansas.

| The title game was a close, hard-fought affair which upon reflection actually turned early in the game. Haskins used a three-guard lineup (by starting 5-6 Willie Worsley) to counteract Kentucky's speed and ball-handling. With the score 10-9, Western, Bobby Joe Hill stole the ball at midcourt from Tommy Kron and sprinted down for the lay-up. The next play, Hill again stole the ball, this time from Dampier, and scored. That was the turning point.

I wish I could forget those two steals," Dampier said. "I wish I could say that he fouled me, but he didn't. I was changing directions, dribbling with my left hand . . .and then it was gone. I can never forget it, either, because my wife has an 8-by-10 picture of it hanging on our wall." by Jo-Ann Barnas, Detroit Free Press, "They Changed the Game Texas Western," March 29, 1996. |

The insertion of Worsley gave Kentucky a height advantage at that position. He was assigned to guard Larry Conley who was nine inches taller than the Texas Western player. UK tried to take advantage of the mismatch on the offensive end,

Rupp continually called plays for Conley to get the ball on the blocks and shoot over Worsley, but that strategy failed when Conley - like the rest of his Wildcat teammates - couldn't get his shots to fall. - by Anthony Holden, CBS SportsLine, "Texas Western Stuns Kentucky," 1999.

Kentucky would make some rallies as the game progressed but the strong inside play of David Lattin and the consistent ball-handling and solid free-throw shooting of the Western guards ensured the victory.

"We had no idea what we were getting into," [Pat] Riley said. "In those days, players didn't dunk. I hadn't seen anyone dunk. Guys barely jumped high enough to stick a dollar bill under their shoes. But these guys came out, and after they had dunked on me about three times, I knew they had a lot more to accomplish than we did." - by Jere Longman, Philadelphia Inquirer, "Forget the Glitter, Riley is a Coach of Substance," June 8, 1987.

- Saturday, March 19 1966 -

NCAA Championship (at College Park, MD)

Kentucky - 65 (Head Coach:Adolph Rupp) - [Final Rank 1st by AP and 1st by UPI ]

| Player | Min | FG | FGA | FT | FTA | Reb | PF | Ast | TO | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Louie Dampier | 40 | 7 | 18 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 19 |

| Tommy Kron | 33 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Larry Conley | 35 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 10 |

| Pat Riley | 40 | 8 | 22 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 19 |

| Thad Jaracz | 28 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Cliff Berger | 12 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Gary Gamble | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jim LeMaster | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bob Tallent | 7 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Totals | 200 | 27 | 70 | 11 | 13 | 33 | 23 | 6 | 16 | 65 |

Texas Western - 72 (Head Coach: Don Haskins) - [Final Rank 3rd by AP and 3rd by UPI]

| Player | Min | FG | FGA | FT | FTA | Reb | PF | Ast | TO | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bobby Joe Hill | 40 | 7 | 17 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 20 |

| Orsten Artis | 40 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 15 |

| Nevil Shed | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| David Lattin | 32 | 5 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Willie Cager | 30 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 8 |

| Harry Flournoy | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Willie Worsley | 40 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Totals | 200 | 22 | 49 | 28 | 34 | 35 | 12 | 4 | 18 | 72 |

|

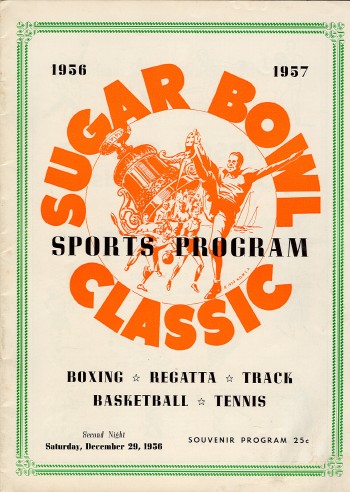

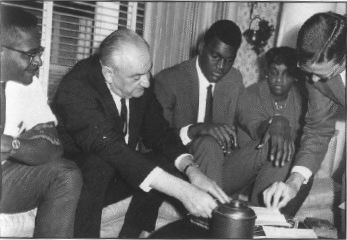

| 1966 NCAA Finals Program |

Preceding the game, there was knowledge that the contest would be special because of the unique racial make-up of the teams, however it was not of the proportions which are often accorded it today.

"All seven of the Texas Western regulars are Negroes, hardly a startling fact nowadays but one that becomes noteworthy because of the likely meeting with Kentucky or Duke. Both those teams are all-white. It is unfortunate -- but it is a fact -- that some Ethniks, both white and Negro, already are referring to the prospective national final as not just a game but a contest for racial honors. More than anything else, however, all four finalists demonstrate that their players are brothers under their recruited skins." - by Frank Deford, Sports Illustrated, "Now There are Four," March 21, 1966.

The players themselves were concentrating on the game at hand.

"We didn't see this as a black-white thing -- we just loved to play ball," - Bobby Joe "Slop" Hill, Texas Western Guard, Bergen Record, March 3, 1996.

"For us, I honestly don't think it was a black-white thing. It was Texas Western going up against Kentucky, who's been there before." - Nevil "The Shadow" Shed, by Jack Wilkinson, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, April 1, 1991.

"It just happened that we had five black starters, and Kentucky had five white starters. We were never coached like that. We weren't into black-white. There weren't any racial slurs. We never heard Pat Riley, Louie Dampier, those great Kentucky players, say a word." - David Lattin, by Dave Kindred The Sporting News, "Haskins truly put his heart into game. Winner of 719 games, national title had his share of suffering," August 31, 1999.

"To us it was a pride game," said Texas Western's Harry Flournoy. "It was just simply an opportunity to show the nation what we had. We didn't say, 'We're going to go out there and whip those white players' butts.'" - by Pat Forde, USA Today, "Legacy of Rupp Slow to Recede Repercussions of 1966 Title Game Still Echo in Many Ears," April 2, 1996.

"That part [black-white] never crossed our minds," say former Texas Western guard Orsten Artis. - by Curry Kirkpatrick, Sports Illustrated, "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," April 1, 1991.

"At the time we were a group of college kids trying to win a national championship," - Kentucky center Thad Jaracz, by Pat Forde, USA Today, "Legacy of Rupp Slow to Recede Repercussions of 1966 Title Game Still Echo in Many Ears," April 2, 1996.

"We didn't even know they had five black starters, for one thing. And there was nothing said about it. We had a lot of calls because, last year, because it was 30 years since that game. And I had calls from L.A., Detroit, all over the country asking me that very question and it was like they were disappointed when I said 'no we weren't thinking about the black-white thing.' And they keep trying to put words into my mouth they say 'well what did you think when you went out to warm-up and saw all those black guys at the other end?' And I was like, 'well they weren't all black.' And besides that, in the final of the regions, we beat Michigan. And they started at least three black guys, if not four." - Louie Dampier in an interview with D.G. Fitzmaurice, Wildcat Legends.

"We didn't think of them as black players, we just thought of them as players. People forget that we beat a Michigan team the week before that had four black starters," - Larry Conley, by John Clay, Lexington Herald Leader, "The Runts: Still Special After All These Years," February 9, 1991.

"I've had a lot of chances to consider this over the last thirty years," said [Larry] Conley, a senior on that Kentucky team, "and it's something that really never entered our minds. We were playing another basketball team. That they started five blacks was inconsequential. All the racial overtones developed much later. We were kids, nineteen, twenty, twenty-one, trying to play a game. I've had several black writers ask me about that since then and I always say, 'Let me tell you something, I wanted to kick their ass all the way back to El Paso.'" - by Frank Fitzpatrick, And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, Simon & Schuster, 1999, pg. 41.

"We didn't know we were going to take part in the Emancipation Proclamation of 1966," [Pat] Riley was to remark jokingly later. - by Ray Sanchez, Basketball's Biggest Upset, Mesa Publishing, 1991, pg. 126-127.

"The only thing that bothers me is that some people think we were motivated by that," Kron said, "by playing an all-black team. That was certainly not the case at all. To me, that's ignorance, and we didn't deserve that. All we cared about was winning the game." - Kentucky guard Tommy Kron, by John Clay, Lexington Herald Leader, "The Runts: Still Special After All These Years," February 9, 1991.

One contradiction to the above was given by Harry Flournoy

"Kentucky was playing for a commemorative wristwatch and the right to say they were national champions," says Flournoy, who averaged 8.3 points and 10.7 rebounds that season. "We were out to prove that it didn't matter what color a person's skin was." - by B.J. Schecter, Sports Illustrated, "Catching Up With . . . Harry Flournoy, Texas Western forward," April 6, 1998.

One interesting aspect of the game was that Haskins only played his seven black players, leaving the remaining five, who happened to be white or hispanic, on the bench. This included Jerry Armstrong, who was Texas Western's most effective defender against Utah's Jerry Chambers in the semifinal game.

JPS Note - Although it should be pointed out that those seven were the top seven players for the Miners that year. Over 94% of the Miners' scoring for that year came from those seven players.

"I just played the five best players, that's all. That's what a coach is supposed to do, isn't it, give your team its best chance?" - Don Haskins, by Dave Kindred The Sporting News, "Haskins truly put his heart into game. Winner of 719 games, national title had his share of suffering," August 31, 1999.

|

No doubt that the 66 title game underscored the important emergence of the black athlete in college basketball."

"In retrospect, that was a historic game. It told everyone, in case the point had been missed, that the game had changed, never to be the same again. The five black starters for Texas Western were too quick for Rupp's all-white team." - by Billy Reed, Louisville Courier-Journal, March 2, 1982.

"You guys got a lot of black kids scholarships around this country," Miners coach Don Haskins said in an emotional address at the [25th Anniversary] reunion. "You can be proud of that. I guess you helped change the world a little bit." - by Jack Wilkinson, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, April 1, 1991.

"I understand why it comes up. They beat them. A team starting all blacks, against a team that started whites. The fact that they were all black made a significant impact." - Tubby Smith, in article by Robyn Norwood, Los Angeles Times (Reprinted in The Sporting News) "At Kentucky, Victories Have No Color," January 14, 1998.

"I didn't get it [the national title] because we played a team that was really prepared to play us," said Conley. "That's all that mattered. Whatever was created, was created without us being involved. We were simply the pawns. We were the pawns of the game. If the African-American community wants to use that as something to better their cause, I don't have a problem with that. If that is a watershed in their history, something vitally important to them, then they can use that. That's fine." - by Frank Fitzpatrick, And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, Simon & Schuster, 1999, pg. 219.

"I don't know that people see us as bad guys," Conley said. "I think they see the game as representative of change. I've talked to a lot of African-American leaders, politicians, coaches of a certain age, and they saw the game as part of social change, a turning point. The Voting Rights Act (federal legislation that struck down barriers to voting for African-Americans in the South) passed in 1964. It was a turbulent time, there was a lot going on. Let's face it, there were a lot of things in society then that needed to change. I think people see that game as part of the change." - Larry Conley, by Mark Story, Lexington Herald Leader, "Winning, Not Race, on Mind of Runts in '66, Conley Says," August 29, 1999.

Reflecting on the game, Kentucky guard Tommy Kron doesn't see symbolism as much as the strategic reality of his team's segregation. "We could've used Wes Unseld." - by Pat Forde, USA Today, "Legacy of Rupp Slow to Recede Repercussions of 1966 Title Game Still Echo in Many Ears," April 2, 1996.

"Only I think years later, can you really take a look at it, and say you know maybe they were playing for something a hell of a lot more significant. And if they were, then the right team won." - Pat Riley, "Glory in Black and White," CBS, April 2002.

Return to top

![]()

Fall-out from the Western Game

Rupp took the loss to Texas Western hard. After the game in which Kentucky shot 27 for 70 from the field, Rupp said "Hell, they just whipped us. That's the story of the game." But, Rupp added, "I'll coach until they haul me away. I hope to be back here again sometime." - by Frank Hyland, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Flashback: 1966: Adolph Rupp's last hurrah,"March 24, 1985 pp B/26.

JPS Note - Although many writers have portrayed Rupp as downbeat immediately after the game [some have suggested that he didn't shake hands with Texas Western coach Don Haskins, a claim which will be discussed in detail and debunked later in this article], it is interesting to contrast that with an actual audio clip from an interview after the game. (Link). In the audio, Rupp does appear concerned about the free throw differential (later in his life, Rupp wondered why UK was called for so many fouls when they were playing a zone while Texas Western was playing an aggressive man-to-man) but overall, he seems upbeat and even has the presence of mind to start talking about the upcoming summer, and joking with interviewer Claude Sullivan about helping him broadcast baseball games (Sullivan was also an announcer for the Cincinnati Reds). In addition, I have yet to see any of the national writers acknowledge what Bob Ingram mentioned in an column (March 26, 1966 - El Paso Herald-Post) that Rupp sent Haskins and Texas Western George McCarty a letter stating: "Your boys played a truly championship game and deserved to win."

Beyond that, not everyone claimed Rupp was downbeat at all. Bob Ingram, sports editor of the El Paso Herald-Post described Rupp in an article after the game as "relaxed, agreeable, jovial and seemingly happy although just a few minutes before the Kentucky team he was reported to have more affection for than any of the teams he ever coached was beaten for the national title."

Despite evidence to the contrary immediately after the game, most national sportswriters in later years ignored that and told the story of a beaten, regretful man.

"The old man really wanted to win it," [Frank] Deford remembered. "He was jealous of [John] Wooden and knew [Lew] Alcindor was on the way." - by John Clay, Lexington Herald Leader "The Runts: Still Special After All These Years," February 9, 1991.

In the end, the administration at Kentucky did have to haul Rupp away from the coach's seat. He never returned to the title game. "That loss to Texas Western hurt me more than you can imagine," Rupp was quoted as saying after his retirement. "Years later I was wondering what I could have done to win that game."

"He [Rupp] dearly wanted to win the 1966 national championship game. He was 64 years old. He might never get that close again. He loved that team, 'Rupp's Runts.' It hurt to lose that one, whether to unknown Texas Western or to another blueblood such as Duke. The coach later told me Texas Western used a player it had gotten out of prison. Well, he no more believed that than he believed Louie Dampier was born in a manger. And he said it knowing I wouldn't believe it, either. He just needed to feel he hadn't been beaten fairly or it wasn't his fault anyway -- a feeling he tried to engender every time Kentucky lost a game to anyone. For 42 years it was his way of dealing with defeat. Acerbic, arrogant, defiant, Adolph Rupp won 875 games and lost none. It was his players who lost those 190." - by Dave Kindred, Lexington Herald Leader, "Calling Rupp a Racist Just Doesn't Ring True," December 22, 1991.

JPS Note - The belief that Texas Western had a former convict was a gross exaggeration based on some rumors which the media at the time of the game allowed to propagate. David Lattin had enrolled at Tennessee A & I (a school, not a prison) in 1963 but dropped out shortly thereafter. There had been a minor disciplinary problem while at the school, but one which was serious enough to cause the Dean of the school to write that Lattin not be readmitted until the matter had been cleared up. Lattin later enrolled at Texas Western. If he had been dismissed from Tennessee A & I, then Lattin would have had to sit out two years before becoming eligible to play basketball. This, however, had not happened and thus Lattin was eligible. - based on a passage from Basketball's Biggest Upset by Ray Sanchez, Mesa Publishing, 1991, pg. 117-118.

This stubbornness to rarely admit defeat most-likely led to a few of the remarks below which Rupp reportedly said and which didn't help Rupp in the eyes of people looking to UK to integrate. The first remark is also unfortunate since Kentucky HAD been recruiting black athletes since 1964, many of them of good academic standing.

In a column by Bill Conlin in the Philadelphia News titled "The Baron Has His Boundaries," Rupp is reported to have replied to the question of whether he should start recruiting blacks. Rupp said, "Humph. I don't think Duke and Kentucky had to apologize to anybody for the way we played without 'em . . . So far we haven't found a boy who meets our scholastic qualifications. It's got to be a Kentucky boy or from a neighbor state. We can't go raid some schoolyard . . . I hate to see those boys from Texas Western win it. Not because of race or anything like that but because of the type of recruiting it represents. Hell, don't you think I could put together a championship team if I went out and got every kid who could jam a ball through a hoop?" - by Ray Sanchez, Basketball's Biggest Upset, Mesa Publishing, 1991, pg. 3.

Adding fuel to the fire, Texas Western SID Eddie Mullens reported that he overheard someone ask Rupp about the play of Bobby Joe Hill, the Western guard who scored twenty points and made the two critical steals. Rupp reportedly said, "He's a good little boy, but there's a lot of good little boys around this year." (by Jo-Ann Barnas Detroit Free Press, "They Changed the Game Texas Western," March 29, 1996.)

Despite the bickering with Rupp, Don Haskins really had bigger worries after the game.

|

"Winning the title focused national attention on the school, and what was discovered embarrassed Haskins. Most of the Texas Western players were either failing academically, or worse, being carried by the school to keep them eligible. Haskins was publicly accused of exploiting his Black recruits for his own glory. For the first time the question of the intellectual cost of athletic integration was being raised. Yes, a basketball scholarship got these brothers into college. But what good did it do them if they made no progress to a degree?" - by Nelson George, Elevating the Game, Harper Collins, 1992, pg. 137.

One of the prime forces behind the questioning of Texas Western was an article by Sports Illustrated in the summer of 1968. Jack Olsen was writing a four-part series on the black athlete and chose UTEP as a case study of a school which had been an early-to-integrate Southern school. (July 15, 1968) Olsen found a school with a wide gulf of misunderstanding separating the white administrators who brought black athletes into the program and the athletes themselves. For example, these school officials continued to use the term "nigger" repeatedly despite direct requests by the black athletes to have them stop. The article went on to reveal how athletes were lured to the Texas El-Paso campus for athletics but then were abandoned from an enriching social or academic life which should expected of a college atmosphere. For example, very few available black women were living in the vicinity yet the reach of the athletic department and coaches was strict in prohibiting interracial dating, leading on a few occasions to athletes being run out of town. In effect, many of the football, basketball and track athletes interviewed for the story felt they were in many ways no better than prisoners.

"They told me that college would be a rewarding experience,"says Fred Carr. "They said I'd meet people, I'd travel. Well, I did, but I still call college the time of my greatest suffering. I came to college and discovered prejudice."

"There is not a thing that goes on here that I like," says Bob Wallace. "We don't have nowhere to go. After every game we are supposed to stay around the dorm playing cards. Nothing to do. Nothing to do. These are supposed to be the best years of our lives, and it turns out to be a drag."

"It's a funny place," says Dave Lattin, now one year removed from the campus. "On the basketball court you're groovy people, but off the court you're animals. Even the Mexicans look down on you."

Above quotes by Jack Olsen, "The Black Athlete," Sports Illustrated, July 15, 1968, pp. 30-43.

JPS Note - This article should be required reading for anyone under the illusion that Texas Western was "enlightened" compared to other programs at the time when it came to the black athlete.

Return to top

![]()

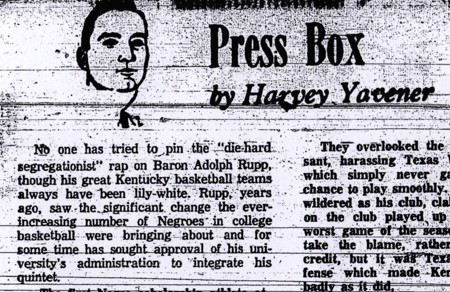

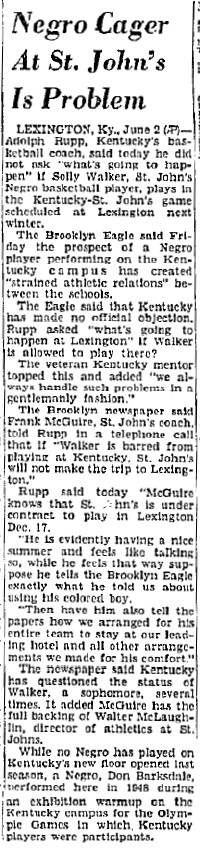

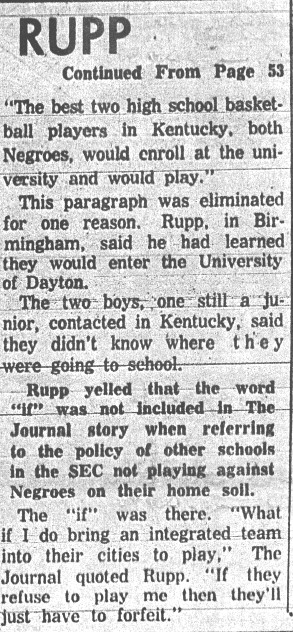

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this entire subject is the role that the media plays in shaping people's attitudes. The modern media, I believe, has done a very poor job dealing with this subject. It seems they either haven't taken the time to realize that this subject is not as clear cut as they've been led to believe, or they choose to ignore the evidence or to understand the time and place that the events occurred in order to make a more entertaining story. Sports Illustrated in particular, has gone beyond lazy journalism and seems to be the prime force driving this characterization of Rupp. Today, these characterizations continue to spread and have become more exaggerated, not based on any new evidence or research but the "common knowledge" based on earlier articles coupled with shoddy journalism.

|

Yavener's article was not only a useful reality check of race relations in the sports world circa 1966, it was nearly prescient in terms of recognizing that those who aren't familiar with the facts might fall into the trap of making simple-minded and incorrect accusations against Rupp.

I would argue that since Yavener's column was published two days after the national final was completed on Saturday night (The Trentonian didn't have a Sunday edition), that over the course of nearly 50 years, media coverage of this game and in particular its comprehension of the issues and the facts have gone downhill since that time. Maybe someday we (collectively) as a society will get back to the same level of knowledge and understanding that Yavener exhibited in March of 1966, but frankly there's a long way to go and we're not very close. This is largely due to the ignorance and various agendas of those in the media, who have consistently undervalued the full set of facts and failed to provide their readers with fair and comprehensive coverage of this issue. If anything, they've moved knowledge of the issues in the wrong direction.

The belief that Rupp is racist is an alluring one, not only because it demeans the accomplishments of the man who so thoroughly dominated his profession but also because it adds drama to the game in 1966 against Texas Western. The mere spectacle of five whites competing against five blacks on a national stage in the 1960's, both vying for the crown could have been dramatic enough, but the story is made even more interesting if sportswriters can somehow paint Rupp as an evil man, a symbol of the segregation and injustice against blacks, and thus make the loss more fitting. As a sports columnist wrote,

"So visible was The Baron, and so racist were his views, that he was the predominant reason why Texas Western's 83-79 victory is remembered a watershed moment in sports history." - by Dave D'Alessandro, Bergen Record, March 3,1996.

"In this racial drama, a perfect morality play for the decade's heightened social consciousness, Rupp and Haskins were cast perfectly. Rupp, the snarling epitome of an unyielding establishment, made a compelling villain. Haskins, the laconic loner who rode in from the West, was an appealing American hero." - by Frank Fitzpatrick, And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, Simon & Schuster, 1999, pg. 36.

"The script for this tidy little morality play called for a colossus of a coach, a legend who had hung four NCAA title banners in his gym, a stubborn man who showed little inclination to change with the times. Every morality play calls for a villain. Although Rupp wasn't that so much as an old man anchored in the past, he would do splendidly." - by Pat Forde, USA Today, "Legacy of Rupp Slow to Recede Repercussions of 1966 Title Game Still Echo in Many Ears," April 2, 1996.

"Basketball's racial evolution simply moved in step with the nation's. One game changed nothing. Still, Sports Illustrated had a case to make, and make it the magazine damn well would. The first thing you need in such a racial case is a villain, preferably one wearing white sheets. So the magazine, using flimsy evidence and unsupported characterizations, portrayed Rupp as a 'charming p.r. rogue' whose politics 'learned toward the KKK.'" - by Dave Kindred, Lexington Herald Leader, "Calling Rupp a Racist Just Doesn't Ring True," December 22, 1991.

"To read and hear the most irresponsible rhetoric, you would have thought that Rupp conducted his practices not in starched khaki shirt and pants but in a white hood and a sheet. You would have thought that, compared with Rupp, George Wallace was a civil-rights advocate. . . Never mind that most of this stuff comes from individuals who never met Rupp nor saw one of his teams play. They have no clue about what Rupp was really like and, frankly, they don't care to find out." - by Billy Reed, Lexington Herald Leader, "Criticism of Rupp Went Way Overboard," March 1997.

"Coach Rupp is made to symbolize the demon, and the demon was much bigger than he was." - Perry Wallace, "Glory in Black and White," CBS, April 2002.

It's very wrong to put that burden on Adolph Rupp. Adolph Rupp was not responsible for discrimination. Our society was responsible for creating an environment which was conducive to accept that. - John Thompson, "Glory in Black and White," CBS, April 2002.

After Rupp died in the middle-1970s, and was not in the position to refute his critics, the racist spin on the game began to make its rounds and it has continued to grow on its own.

"That belief (Kentucky is overtly racist) was given life by a Sports Illustrated article on the 25th anniversary of the 1966 NCAA Championship game ... With no evidence beyond gossip, the magazine indicted the Kentucky coach, Adolph Rupp, accusing him of politics leaning to the Ku Klux Klan. Rupp-as-racist stories now have been so embellished that the average basketball fan can be forgiven for imagining Rupp burning a cross in the yard of any black player who dared think of playing at Kentucky. That image is a lie." - by Dave Kindred, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, "Facts Belie Stereotype of Racist Rupp at UK," May 11, 1997.

"Rupp after his death, became a racist. The media decided that he was a bogey man that we could pin this on now. The 66 game, the Texas Western game set that in the minds of a lot of sportswriters, and other media, who weren't there, who didn't know Adolph, who had never been around him in any situation. But it became a model, a symbol really of the black arrival in basketball. It became a convenient historical point." - Dave Kindred, "Basketball in Kentucky - Great Balls of Fire", WKET, 2002.The story by Sports Illustrated prompted political columnist George Will to call Rupp "a great coach and a bad man." (George Will, Philadelphia Inquirer, "Basketball, The Team Game That Can be Practiced Alone, Has its 100th Birthday," December 19, 1991.) These attacks caused Rupp's surviving family to take offense. "How can George Will be that ignorant and dumb?" he [Herky Rupp] say. . . ."I don't see how you can even say what they [SI] say in there," she [granddaughter Farren] tells her mother. "I don't see how you can even say what they say." (Robert Kaiser, Lexington Herald Leader, "Loyal to the Legend, Coach Adolph Rupp's Family Strives to Return Luster to his Reputation," March 14, 1993.)

Curry Kirkpatrick claims in his article "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" (Sports Illustrated, April 1, 1991) that the mere fact that five black starters played against a entirely white team was not what was important. What was important was that Rupp lost.

"I always wondered if there would have been all the interest if Texas Western had beaten Duke [Kentucky's NCAA semifinal victim and also all-white] instead of us" says Larry Conley, a Wildcat starter in '65-66.

To which Kirkpatrick replies in the article

"Hardly. This was Texas Western and this was Rupp. Every Quixote needs his windmill. Against the Miners in '66, the Man in the Brown Suit was twirling round and round in a gale."

"But the game was about more than just the obvious. Today, in fact,it's easy to make the argument that it has become more about changes in the media than changes in college basketball or society. The 1960s columnists and commentators who supported segregation or treated it with benign neglect have been replaced by self-appointed moral authorities who are, in their own way, just as narrowminded and prejudiced." - by Billy Reed, "The Revising of Rupp," Basketball Times Vol. 25, No. 5, January 2003.

![]()

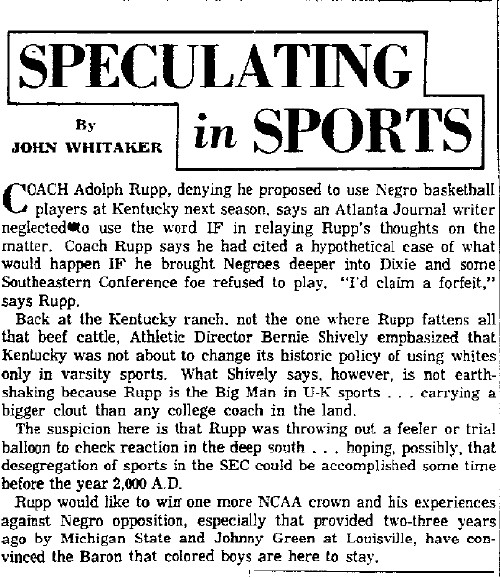

Motivations for Perpetuating the Charge

| Recruiting | Comparisons to other Programs | Distractions from Others |

The racist charge still carries weight as fans of other schools can point to it to sway potential players from the school. To this day, players are pulled away from UK by this angle, a recent example being Jason Osborne of Louisville whose grandparents told then-UK coach Rick Pitino that no grandchild of theirs would set foot on the campus of Rupp's university. (Sports Illustrated, "On the Scene," April 1996.)

A report aired by ESPN (May 12, 1997) that explored how receptive Kentucky would be to a black man (Orlando "Tubby" Smith) coaching the UK basketball program helped persuade Bryon Mouton to stay in Louisiana and attend Tulane.

"I don't know Coach Smith that well, but right now at Kentucky, there's a lot of controversy with race involved," Mouton said. "There's big pressure for him to win and, right now, I don't need to go into a situation like that." - by Jerry Tipton, Lexington Herald Leader, "Mouton Chooses Tulane, Near Home," May 16, 1997.

Other fans may only be interested in order to dismiss Rupp's accomplishments on the court in order to favor other coaches or programs legacies.

"And even with his four national championships Rupp will always be viewed in the mirror of the Texas Western game, where he was on the wrong side of history. Rupp never recovered from that. And for many black Americans, neither did Kentucky." - by Tony Kornheiser, Washington Post, "To Tubby: May the Best Man Win," May 15, 1997.

"Dean Smith has been a paragon of grace, integrity and class. That is in stark contrast to the man he replaced as college basketball's alltime winningest coach, Kentucky's Adolph Rupp, who was the game's George Wallace when it came to integrating black players. For most of his career, Rupp fought tooth and nail against the inclusion of blacks into the game. His all-white team's loss to all-black Texas Western in the 1966 NCAA championship games has often been called the Brown v. Board of Education of college basketball. Smith, meanwhile, was at the vanguard of that movement. . . . Garnering win No. 877 was a remarkable achievement for Dean Smith, but in my mind, when it comes to the things that really matter, Dean Smith surpassed Adolph Rupp a long, long time ago." - by Seth Davis, Sports Illustrated, March 1997.

JPS Note - It is interesting to note that the last all-white team to make the Final Four was not Rupp's 1966 squad but Dean Smith's 1967 North Carolina squad.

When Dean Smith retired from coaching just prior to the beginning of the 1997-98 season, he had surpassed Adolph Rupp in all-time career victories with 879. The day after he announced his retirement, noted UK critic John Feinstein couldn't resist the temptation to denounce Rupp.

Host Alex Chadwick: "He [Smith] retired after beating Adolph Rupp's record for wins. Was that an important thing for him?"

Feinstein: "No. If he would have had 875 wins, one short of Rupp, he would have still retired. He was never about numbers. And he was uncomfortable being mentioned in the same sentence with Rupp Because Rupp, of course was a segregationalist. Throughout much his coaching career. He was sort of dragged kicking and screaming to integrate his teams. He [Smith] was never comfortable with that connection." - National Public Radio, October 10, 1997.

USA Today ran a story on November 15, 1996 where they identified college basketball's premier program as Kansas. Although Kansas only holds two NCAA Tournament championships (compared to Kentucky's 6 (at the time) and UCLA's 11) and lags behind in all-time wins and winning percentage (categories Kentucky leads), the newspaper cited criteria such as Tradition, Current Stature, Coaching, Setting etc. in coming to their conclusion. Kentucky is at least the equal or better in those categories with respect to Kansas. So why was the decision made in favor of KU? The paper cited:

JPS Note - Kansas also drew NCAA probation in the 50's and the late 80's for recruiting irregularities so perhaps the charge against Rupp tipped the scales in KU's favor?

It is clear that some have benefitted from the label of the University of Kentucky (or the state) being racist. A look at UK's recruiting failures in the city of Louisville is a visible example. Beyond the use of race as a recruiting tool and instrument for fans to dismiss Kentucky's accomplishments, there is a more insidious reason behind the media attention accorded Kentucky and race. This can be traced to the fact that racism was (and still is) prevalent all over the country and concentrating on one man and one school allows others to point fingers without considering how they, their ancestors, or their school dealt with racism at the time, and even today.