![]()

![]()

![]()

| Overview | Point Shaving | Alex Groza and Ralph Beard | Bill Spivey | Streit's Charges | Kentucky's Response | Banishment SEC | Banishment NCAA | Lost Season | 1953-54 Season | Aftermath | Bitter Feelings | Postscript |

Kentucky played no schedule for the 1952-53 season as part of the fall-out from a scandal which rocked the nation in 1951. Revelations of point shaving and dumping games came to light when Junius Kellogg, a star of the Manhattan Jaspers basketball squad, was approached by a former player and offered $1000 to dump an upcoming game. Kellogg reported the incident to authorities and the New York District Attorney's office was called in to investigate and make the arrest. The investigation that followed, under the direction of Manhattan District Attorney Frank Hogan, led to the unearthing of such widespread gambling and corruption within college basketball that it implicated thirty-three players in eighty-six games, with the knowledge that many more got away.

|

The mecca of college basketball up to that time, Madison Square Garden where many of the fixes occurred, was shunned after the scandal, (including Coach Adolph Rupp who didn't return to the Garden until very late in his life when he went to watch the 1975-76 team play in the NIT Tournament.) Many of the great New York programs, including City College of New York and Long Island University had their programs de-emphasized and they never returned to their former glory. Other schools, including many of the catholic schools around New York City such as St. Johns, were inexplicably spared. Although the investigation was mainly centered in New York, gambling connections were made to the rest of the country including Bradley, Toledo and eventually the University of Kentucky, the most dominant basketball program at the time.

Sidebar: New York City Scandals The spectre of a gambling scandal was nothing new to those in New York City, where rules and regulations concerning amateurism was flaunted as college players regularly competed for pay under assumed names around the city. The culture was one that had long been established since at least the 1920s if not sooner. In 1945, the New York District Attorney's office accidentally stumbled into a gambling scheme concerning Brooklyn College. Five members of the school were implicated and expelled, but that did nothing to change the overriding culture as it was suggested to be an isolated incident.

That same year an article in a sports column ("You Don't Say!" by Mac, Dunkirk (NY) Evening Observer, April 4, 1945) illustrates how wide open the knowledge of cheating was; that is for those who were paying attention. Down in Panama Sgt. John O. Jones, formerly of Saratoga Springs, is startled to learn how shocked New York was over the basketball scandal. Sgt. Jones used to be publicity director for an entry in the New York State Professional Basketball league and says he observed too well the tactics not only of metropolitan stars, but their coaches as well. He wonders what New York expected in view of the background of its college players which is hardly lily white. He adds "I know a lot of those boys personally, and their attitude in regard to sports. You couldn't even trust them in a pro grame. Hire one for $25, and if he made 15 points he'd ask you for a big raise just before the next game started. Unless he got it, he would refuse to go on the floor, leaving you in a hole. Some tall stories could be told without stretching the truth one iota. "Pro loops in Massachusetts, Connecticut and Maine drew talent from the rich New York college field. The practice of college players performing with the pros under aliases was generally overlooked by the coaches of New York University, Brooklyn St. John's , Fordham, City College of New York, Brooklyn College, Brooklyn St. Francis and Long Island University. "In fact, one coach made only the stipulation that his ace floorman should not compete professionally the night before his college club went into action. His only objection was having a tired player for an important college contest. "Long Island U's Blackbirds, "home team" at the Garden so many seasons, were little less than professionals. During the summer they served as lifeguards at Manhattan Beach where they played outdoors and practiced some more. "Other metropolitan coaches disliked Clair Bee's tactics, preferred not to tackle the Blackbirds, but said nothing because their houses were far from clean. Promoter Ned Irish had to bring in such as West Texas Teachers as Blackbird opponents. "Look over the professional backgrounds of Nat Holman of City College and Joe Lapchick of St. John's, both members of the famous Original Celtics and you will understand why they might have had no objection to their charges playing a little pro ball on the side. "One New York team had a remarkable season, yet was denied an entry, by its college board, to the National Invitation Tournament at the Garden. The following winter, with almost the same talent, the club won and lost as it pleased - or should I say, as the gamblers pleased." |

"Those guys were smooth talkers. They should have been salesmen. They took us out for a stroll, treated us to a meal, and before we knew anything, we were right in the middle of it. They said we didn't have to dump the game. They said nobody would get hurt except other gamblers. They said everybody was doing it. And they asked what was wrong with winning a game by as many points as we could. We just didn't think. But if somebody suspected what was going on at the Garden had warned us that things like that were against the law, we'd never have done it." - Dale Barnstable, excerpted from Scandals of '51 by Charley Rosen, reprinted by Seven Stories Press, 1999, pg. 182.

|

The players again agreed to try to play over the point spread in a 56-45 win against DePaul and a 72-50 win against Vanderbilt. On February 8, 1949, the players (according to Englisis pushed by Groza because the gamblers were willing to pay more for 'unders') agreed for the first time to play under the point spread. Kentucky did win the game against Tennessee 71-56, a margin a 15 points which just did fall under the 18-point line. Groza scored 34 points in that game.

The team was 29-1 when they entered the NIT Tournament. Playing against the 16th and lowest-seeded team, Loyola of Chicago, the heavily favored Wildcats were shocked 67-56. According to Charley Rosen's book, Scandals of '51, the difference was Groza's poor attempts at guarding Loyola star Jack Kerris.

According to Englisis in his rendition of the game events, he suggests that what occurred in the Loyola game was Groza realized in the second half that Kentucky might lose (they were behind by one point at halftime) and in an attempt to become more active, began to foul. This eventually lead to Groza fouling out. On his fifth foul, Groza returned to the bench and cried into his towel. Without their big man (along with forward Wah Wah Jones who also had fouled out), Kentucky was vulnerable to the upset.

Beard, who led the team with 15 points swore "On my children's eye, I never did anything to influence the outcome of a ballgame. I just took the money and never looked back." (Tampa Tribune, March 26, 1999). Englisis in his 1952 article claimed "Beard fouled out and walked off the court chewing his gum like a piston. He sat down and kept his head on his chest. I guess he also was counting the dough he lost." Beard disputed this charge immediately after it became public, correctly mentioning that he didn't even foul out of the game as Englisis claimed.

Rupp was devastated after the loss, reportedly saying to Bernie Shively as he downed a fifth of whiskey, "I don't know...Lordy. But I think there's something wrong with this team." The three players were paid a total of $1500 for their work.

|

Despite the loss, the team went on to enter the NCAA Tournament. According to Englisis, the players tried to play over (rather than under) the 14-point point spread against Villanova in a first round game because as Groza told him: "The little guy (Beard) and Barnstable are worried about losing that one too. They're afraid somebody might get wise to what we've been doing." Despite 30 points from Groza, Kentucky could not put away the Villanova Wildcats as Paul Arizin matched Groza's point total and the final margin of victory was 13-points, just under the spread. Englisis, who had lost big on an earlier attempted fix on a game between Bradley and Bowling Green in the NIT, bet everything he had left on the 'over' for the Villanova contest and went broke on the game. With their patron out of money, that was end of the fixing for those UK players. Kentucky went on beat Oklahoma A & M to win a second NCAA title.

With the graduation of Beard and Groza, the game fixing did not end. Dale Barnstable was still eligible on the 1949-50 team and he was joined by Walter Hirsch and Jim Line. The three conspired with Englisis and his associates, including boss Eli Kaye, to shave points in a game against DePaul and a few weeks later against Arkansas.

The next season, Bill Spivey, Rupp's first seven-footer, reportedly joined the group of fixers. According to Jim Line, Spivey and Hirsch were offered $2500 to shave points in the Sugar Bowl Tournament that year. Kentucky ended up losing the first game to St. Louis University in overtime 43-42. Kentucky won the next game in the tournament against Syracuse by 10. The loss to the Billikens was only one of two games lost all year. The Wildcats went on to win their third national championship that season.

|

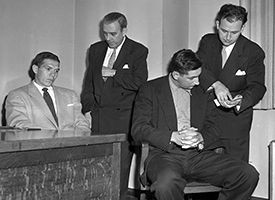

On October 19, 1951, there was a double-header being held at Chicago Stadium. On the ticket were the US Stars versus the Harlem Globetrotters with the nightcap being the NBA champion Rochester Royals versus a team of collegiate all-stars (coached by UK coach Adolph Rupp). Beard and Groza were en route to training camp for the Olympians when they decided to stop in Chicago to see the double-header and catch up with their old coach. Detectives arrested the two outside the stadium after the games were over and Barnstable was awoken by police at 2 a.m. the same night at his home in Louisville (leaving his wife and twin 5-month old daughters). The players were held for over seven hours by the Chicago police, without the benefit of any legal representation.

The players were fully cooperative with the investigation, as evidenced by a statement by New York Assistant District Attorney Vincent O'Connor to the court that was sitting in judgement of the players.

| "With respect to the defendants before the court for sentence, I do know that they have previously given your honor information concerning the details of their involvement and their personal family and environmental background.

"On behalf of the District Atty. Hogan I am going to ask for clemency for these defendants. "I first met Groza and Beard last October in Chicago in the office of the Cook county prosecutor, the Hon. John S. Boyle, who has co-operated splendidly in several phases of our investigation. At the same time my associate, Asst. Dist. Atty. William P. Sirignano, was in Louisville, questioning Barnstable.

"Our appeal to these young men was that which had secured the facts from every player questioned throughout the entire basketball fix inquiry with the single exception of the misguided and ill-advised Spivey. "It was: That the players owed it to themselves, to their families, to their universities, to society and to the sport itself to help us clean out widespread corruption which threatened basketball's very existence. If that meant involving themselves, it was only because the truth called for such involvement. "We told them to place confidence in us to be fair to them if they were of assistance to our inquiry. "When Groza and Beard had responded and given me the facts I asked Groza to speak over the telephone to Louisville to Barnstable and encourage him to be frank and open. "None present, I am sure, will forget that tense moment in the Chicago prosecutor's office when Groza said over the long-distance telephone to Barnstable, 'Barney, Ralph and I have told these men the truth, and I think you should do the same. You'll feel all the better for it.' "Barnstable quickly, then, did tell Mr. Sirignano the truth, for he, like Groza and Beard, and the many players from New York, Ohio, Illinois and Kentucky, were possessed of the stuff for rehabilitation and rebuilding worthwhile and useful lives. "These three defendants became of substantial aid to our office. Groza and Beard waived extradition and came to New York. Barnstable voluntarily accompanied a detective from Kentucky for arrest here. All three expressed desired to waive immunity and testify before the grand jury. "They were content to trust our advice that while they faced prosecution it would be to their best interests to co-operate fully. It was only at our urging that they sought advice of counsel, the New York attorney appointed for them by the court. "They were important witnesses in the grand jury. Testimony given by them has contributed substantially to the indictment of eight fixers, four of whom have already been convicted by guilty pleas entered in the face of overwhelming proof. "The defendants are available as trial witnesses should it become necessary to call them to bring to justice the remainder of the fixers whose prosecutions are pending. We told these young men that at the appropriate time we would ask the court to consider their cooperation with our office in passing judgement on them. At the time of their formal admission of guilt the court accepted misdemeanor rather than felony pleas from them on our recommendation. "In the opinion of Dist. Atty. Hogan, regard for facts, objectivity of judgement, duty to society and the dictates of human sympathy all united to justify my asking extreme clemency for these young men. On his behalf, therefore, I respectfully recommend suspension of sentences on each of these defendants." (excerpt from "O'Connor Asks Leniency, Praises 'Co-Operation', Lexington Herald, April 30, 1952.) |

|

"They told us that we were banned from the league for life. And that was it. Just like that, it was the end of my career. I was ruined at 23 years old. Can you imagine how that'd make you feel at 23? All I ever wanted to do was be a professional basketball player. And, of course, Alex and I were. We owned our own team. We were on top of the world. Now it was all gone. I'd lost everything. I was humiliated. I was ridiculed. I was branded a criminal. You know, stuff like that just never goes away." - Ralph Beard in Pioneers of the Hardwood by Todd Gould, Indiana University Press, (1998) pg. 194.

After the three received a suspended sentence and indefinite probation for their roles, Beard was heard to say,

"Yes, I'm guilty. Let me out of here. Let me die." - Scandals of '51, by Charley Rosen, pg. 202.

|

Instead of being pioneer owners of an NBA franchise (worth many millions of dollars today) and likely Hall of Fame players, Beard and Groza were bothered by thoughts of what could have been and being actively prevented from participating in the game they loved. Even fifty years later, the sense of loss still haunted Beard.

"I loved this game," Beard said by telephone the other day. "I loved it. It isn't like losing one of my kids. It isn't like losing my wife Betty. It isn't like going blind. But I'm telling you what - it will be with me until they hit me in the face with that first spade full of dirt - because basketball was my life." - by Martin Fennelly, "A Mistake that Changes a Life," Tampa Tribune, March 26, 1999.

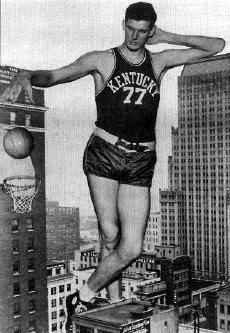

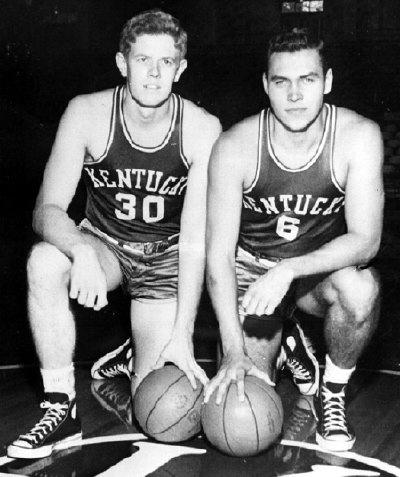

As the 1951-52 season commenced, Kentucky was primed to have perhaps their most powerful team of all-time, even more potent than the Fabulous Five. Future Hall of Famers Cliff Hagan and Frank Ramsey were the cornerstones of a very talented squad. Seven-foot center Bill Spivey was in his senior season and hoped to live up to the immense national hype that surrounded him and demonstrate that he was indeed the most dominant center in the college game. He had to recover from knee surgery and that delayed his season.

|

As the season flittered away with no resolution in sight, Spivey decided to travel to New York where he spoke privately with O'Connor and to the grand jury in order to clear his name. Former teammates Jim Line and Walter Hirsch had testified that Spivey was a willing participant in the point shaving. Spivey claimed under oath that he was innocent of fixing games, stating that he had been approached twice but refused. He did, however, admit to not reporting the incidents. This was in accordance with public comments he made during the season prior to coming to New York. (Spivey was the only accused player in the entire scandal to claim innocence. The rest admitted their guilt and received suspended sentences (although their basketball careers were effectively over)).

"I could not have been involved in such fixing because of my loyalty to my school, to the people who believe in me, and because of my love for the game." - Bill Spivey, in Scandals of '51 by Charley Rosen, reprinted by Seven Stories Press (1999) pg. 202.

After the testimony, Spivey returned to Kentucky feeling that he had vindicated himself and expressed hope that he could be reinstated in time for the NCAA tournament. [For his part, Coach Rupp when asked about the prospect of Spivey returning to the team stated that "We organized our team this year to take care of the loss of Spivey. We have a winning combination which I would not care to disrupt by a sudden change." (Lima (OH) News, March 3, 1952). In retrospect, Kentucky could have used Spivey when they got beat by St. John's in the NCAA tournament that year. The Redmen's Bob Zawoluk, a All-American center who Spivey had contained in previous games, exploded for 32 points in the victory.]

But the winds of change were not in Spivey's favor. Line returned to New York from Kansas (where he had begun working as an engineer) and stood by his testimony that Spivey was involved. When the New York authorities offered Spivey a chance to return to the witness stand to correct any errors or omissions in his previous testimony, Spivey refused, stating that if there was any discrepancy between his testimony and that of others, it was not on his part.

Meanwhile, Assistant District Attorney Vincent O'Connor reportedly said 'that Spivey might beat him in court, but he would see to it that the Wildcat star would never play professional basketball.'

"I find it hard to believe the O'Connor would say anything like that," Spivey countered "especially since he has no evidence that I am guilty in any way of any connection with any phase of the basketball scandal." (above two quotes from "Flashback: Dark Days at Kentucky" by Russell Rice, Big Blue Basketball Vol. 3, No. 1 March 1989)

|

Soon after Spivey's testimony, the University Athletic Board voted to terminate his eligibility at the school. "Kentucky said I couldn't come back until I proved my innocence. They took my grant away, and I went hungry for three days. I remember the local headlines said: 'Spivey May Get Five Years.' I was found guilty in my own town before I ever went to trial.'" ("Flashback: Dark Days at Kentucky" by Russell Rice, Big Blue Basketball, Vol. 1 No. 1, March 1989)

|

In coming to their decision the UK athletic board cited discrepancies in Spivey's testimony to the grand jury (where he admitted to being approached by gamblers) and earlier discussions with University officials (where he failed to mention these encounters) along with information in the Grand Jury transcripts and confidential evidence from the District Attorney's office. The university believed that Spivey was involved in fixing a game in the Sugar Bowl against St. Louis, a game UK lost 43-42. (Note that in this game, not only did Spivey lead all scorers with 16 points, but he made 8 of 10 free throws; a high percentage which would seem to contradict the claim of point-shaving. In addition, it was determined that the two players that Spivey guarded during the game only scored a total of four points during the course of the contest.)

The discrepancy between Spivey's testimony and that of his former teammates led to an indictment of Spivey for perjury that spring, with a trial set for January of 1953.

Spivey maintained his innocence and felt understandably betrayed by the University. "Instead of getting behind me and trying to help me out after my name had been pulled into this awful fix case, university officials went against me and suspended me from school without bringing any charge whatsoever." said the bitter player.

Responded UK official Dr. Leo Chamberlain, "The public will have to await the [court] verdict. I have no fear of what the verdict will be." (above two quote from The Rupp Years by Tev Laudeman, 1972)

As it turned out Chamberlain was a bit presumptuous in his assessment of the situation. The perjury trial resulted in a hung jury with a 9-3 margin in favor of acquittal of Spivey. He was never convicted of any wrongdoing and continued to proclaim innocence, even passing a lie detector test to that effect.

For their part, the state was unable to get Jack West, the fixer they charged that Spivey colluded with, to testify against the player, even though West was already in jail and presumably stood to gain from cooperating with the authorities. Eli Klukofsky (alias Eli Kaye), the mastermind of many of the fixes, was also unavailable as he suffered a fatal heart attack while awaiting trial.

Vincent O'Connor attempted to enter into the court record evidence from the telephone company that a phone call had been placed from Lexington KY to West's phone number in New York, with O'Connor suggesting that it was Spivey who made the call. However Judge Streit threw out the evidence, given that it could not be proven the identity of the caller.

With the inconclusive jury results, the case was thrown out. Given a general lack of evidence against Spivey, the state gave up pursuit of the case. But Spivey was never vindicated completely.

|

Spivey wanted to sue the league at the time but was informed by his then-attorney John Y. Brown Sr. that bringing the suit would require $8,500; funds Spivey didn't have. "For the lack of $8,500, I guess I gave up a couple of million." reportedly said Spivey. This left Spivey to wander the backwater of basketball, playing in second-class leagues for the rest of his career.

"It absolutely ruined him [Spivey]," said UK Athletics Director C.M. Newton, a college teammate and roommate of Spivey's. "It kept him from an NBA career. And, at that time, you didn't just go and get a lawyer like you do now. There was a lot of intimidation." If Spivey had not had his career aborted, Newton said he would have gone down among the game's all-time greats. "He would have rewritten all the records in the pros," Newton said. "They would have had to change the rules for him. He was that dominant." - by Mark Story, "Spivey, Mashburn, Riley reach Rupp rafters," Lexington Herald Leader, January 20, 2000.

Spivey went on to play in the minor leagues for over 25 years. At one time, he squared off against Wilt Chamberlain in an exhibition game and held his ground (scoring 30 points and grabbing 23 rebounds to Chamberlain's 31 and 27) against the big man who would eventually become one of the greatest players in NBA history. Spivey's minor league professional career is as follows.

In 1959, the Cincinnati Royals expressed an interest in signing Spivey to an NBA contract but was rebuffed once again by Commissioner Podoloff.

|

He [Spivey] was so good, two years ago, the Cincinnati Royals drafted him from the Baltimore Bullets. They offered him $20,000 - $7,000 to drop charges against the league, $3000 to buy off Baltimore and $10,000 to play pivot for rookie Oscar Robertson. Podoloff again blocked the shot, stepped in and threatened to boycott the Royals if they played Spivey. They had to bow, but offered him a job taking tickets. Spivey sued Podoloff for $820,000, later withdrew it and substituted a federal suit charging the NBA with violation of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. When Podoloff read that complaint he called a foul on himself, offered Spivey $10,000 if he would drop the suit and agree never to start another. Bill was torn. He wanted to hold out for re-instatement but the court docket was such that even if successful he would be too old to play by the time he got it. Reluctantly, he took the money. "I don't mind when it was only me. But when it began to hurt my wife and child, it hurt me. It was at least some vindication." ("Athletics' Victim," by Jim Murray, Oakland Tribune, November 2, 1961, pg. 49.) |

That $10,000 was all Spivey would ever get from the league that spurned him. He could have been one of the all-time greats. Instead, he lived his life and died a bitter man.

In an interview with Adolph Rupp in 1974 after Rupp had been named as the all-time top SEC coach alongside three-teams of players, Rupp made sure to include mention of his big man who was not named to any of the teams: "I'm sure if Spivey had had the opportunity to play his final season, he possibly would have been one of the outstanding center of all time anywhere - like (Lew) Alcindor of UCLA," Rupp commented. ("Rupp, UK top All-SEC, but ..." by Bob Adair, Louisville Courier Journal, February 25, 1974.)

When asked about Spivey by longtime NBA superscout Marty Blake, Blake remarked, "He was a big-time center. Where he fits, I don't know. He never got that chance." ("Unfair Denial of NBA Dream Haunted Spivey," by Gregg Doyel, CBS Sportsline, June 15, 2005.)

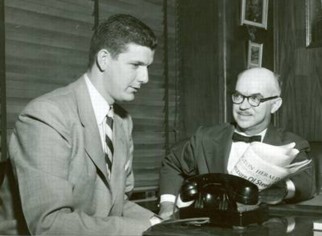

The scandal also hit the University and Coach Rupp hard. In return for a lesser charge (conspiracy rather than accepting a bribe), the players had agreed to testify against the fixers and to provide details about the basketball program. With no formal trial at hand, no defense attorney's present (and therefore no cross-examination of the statements), the presiding judge (Manhattan General Sessions Judge Saul Streit) took the opportunity in interviewing the players (and others) directly and in detail.

Sidebar: Saul Streit Manhattan General Sessions Judge Saul S. Streit sat in judgement of the numerous basketball players who had chosen to plead guilty to lesser charges of conspiracy (which was a misdemeanor) rather than facing a more serious charge of accepting a bribe. In the process of determining the sentence, Streit chose to do his own interrogations of the players.

The same day that the Wildcats would be nabbed by police in Chicago, Streit in reference to the sentencing of 14 players from LIU, CCNY, and NYU had noted the "shocking situation" and stated that "commercialism and over-emphasis" in football and basketball is "rampant throughout the country." (Associated Press, November 20, 1951). Streit continued "Even a cursory examination of recent surveys, spot checks and reports concerning intercollegiate football reveals a chronic, insidious condition which, if not checked, must explode into an atomic scandal which will dwarf the charges before me into insignificance." (INS, November 20, 1951) As far as the coaches involved (Clair Bee of LIU and Nat Holman of CCNY), Streit was just as damning. "The Naivete, the equivocation and the denials of the coaches and their assistants concerning their knowledge of gambling, recruiting and subsidizing would be comical were they not so despicable." (INS, November 20, 1951) Streit was not new to the issue of gambling, as he had sat in judgement during the prosecution of numerous fixers leading up to the basketball scandal, and was very vocal about the evil influences of big time athletics on the amateur ideal. In his opinion, athletic scholarships were illegal and should be abolished. And he made it a point to lobby the NCAA and Congress to take action on the matter. In fact, Streit was so strongly supportive of athletics reform that motions were filed by defense attorneys for him to relieve himself of sitting in judgement of some of the fixers. Streit, however, denied the motions. Streit's barbs came down like missiles on programs all around the country. Tennessee, the University of Pennsylvania, Oklahoma, Bradley, Maryland, Ohio State, Michigan, Southern Methodist, the list went on. The reaction to Streit's numerous blasts from college administrators and President's from around the nation was muted but defiant. They disputed the judge's claims and found his rhetoric to be over the top. Replied Madison "Matty" Bell (SMU Athletic Director) on the topic of athletic scholarships: "Well, it isn't any of the judge's business in the first place and in the second place these scholarships cover all sports, not just football. Only about 90 are for football, both freshman and varsity. We give athletic scholarships in basketball, baseball, track, golf, tennis and swimming. These are given to boys who, in the main, would be unable to attend college without the assistance. In other words, athletics are giving boys an education." (Associated Press, November 20, 1951) Said University of Maryland president Dr. H. Byrd, "Why should we make any change in a system that is working successfully just because of criticism from some obscure fellow in New York?" (Scandals of '51, pg. 197) Noted a sports editor in a weekly column about Streit "Some folks are wondering -- if more college presidents aren't justified in answering the blanket indictments hurled by Judge Saul S. Streit of New York - the man who stands in a mud puddle and makes cracks about the dust on passing autos." (John Whitaker, "Speculating in Sports" Hammond (IN) Times, December 10, 1951, pg 13) When it came time for Kentucky's judgement in May of 1952, there was no surprise in Judge Streit's acrid language, describing the Kentucky program as the "acme of commercialism and overemphasis." Afterall, having the University of Kentucky basketball program on trial was as close to an 'atomic scandal' as the judge could ever hope to dream of to get his point across, which he spent 63-pages trying to make. In response, Kentucky released a statement signed by the governor of the state, Lawrence Wetherby, UK President H.L. Donovan and others. The University did admit to errors which were made, but took exception to many of Streit's findings and claims. Said the statement, Streit's accusations "reflects only his personal opinion, based on meager and sometimes erroneous information, interspersed with statements of fact, but these statements of fact, removed from context and taken together with statements of opinion, have produced a distorted and untrue picture. Our record in this affair is not above criticism and we are firmly resolved to make such reforms as will assure ... that never again shall a scandal besmirch the name of the university." But, "We shall be answerable to the people of Kentucky, to the NCAA and our regional association . . . our policy will not be dictated by Judge Streit." Later on, the statement from UK noted "Our feeling about this is intensified by the realization that in 63 pages of attack upon the athletic policies of the university, its faculty, alumni, trustees and administration, no reference is made to organized gambling in New York and the criminals that produced this scandal. It would be well for Judge Streit to remind himself that not the least responsible by any means are those who have tolerated the unsavory environment in which Madison Square Garden operates." (Associated Press, May 7, 1952) JPS Note: The full Kentucky response to Streits charges are included in the following links (pdf files) - (1) (2) (3) (4) (5). |

When Judge Streit came to announce the sentences for the Kentucky players in May of 1952 (all received suspended sentences), he took the opportunity to present his case for how the overemphasis on athletics by the University played a pivotal role in the corruption of these youth.

Streit labeled the University of Kentucky athletic program as "the acme of commercialism and overemphasis" and blamed Rupp for creating an atmosphere not conducive to the well-being of the student athlete. Streit claimed Rupp "failed in his duty to observe the amateur rules, to build character, and to protect the morals and health of his charges."

Included in the 63-page finding from Streit were such conclusions as "I found that intercollegiate basketball and football at Kentucky have become highly systematized, professionalized and commercialized enterprises. I found covert subsidization of players, ruthless exploitation of athletes, cribbing at examinations, 'illegal' recruiting, a reckless disregard of their physical welfare, matriculation of unqualified students, demoralization of the athletes by the coach...".

Streit singled out Kentucky coach Adolph Rupp who he linked with local Lexington gambler Ed Curd. According to Streit's address "[Alex] Groza said that Mr. Rupp used to show the players slips showing the number of points by which they were favored in every game....

"[Dale] Barnstable testified that in the Sugar Bowl game with St. Louis in January of '49 he missed a shot, following which Rupp came back and gave me the devil and said that shot I missed just cost his friend, Burgess Carey, $500.

"[Ralph] Beard said he remembers the occasion in Cincinnati when Rupp came into the (hotel) room and said, 'I just called Kurd and got the points. We are favored by 15. Now these guys will be tough, so let's pour it on.'" (Associated Press, April 30, 1952).

The "Kurd" in question was Ed Curd, a local Lexington bookmaker who is generally credited with conceiving of the point-spread, an invention which paved the way for increased popularity (and thus revenues) in sports betting. According to Streit's charges, Rupp was criticized for hosting a dinner for Curd in New York's Copacabana Club.

Also cited in the finding was evidence of payments of up to $50 to players by Rupp and other university officials along with numerous boosters. Beard and Barnstable testified that players received $10 to $20 from time to time for playing good games. Walt Hirsch testified that Rupp gave him and the other starters $50 each after a win against Kansas, and later St. John's. Players also were given cash awards by UK for participating in the Sugar Bowl basketball tournament.

Rupp was also criticized for neglecting the physical welfare of his athletes, citing such examples of instructing his players to take novocaine and playing through injuries.

Before the ruling and as part of Streit's discovery process, the judge had ordered the Kentucky State Welfare Commission to investigate Alex Groza, Ralph Beard and Dale Barnstable and to provide a "complete social study on each of the players and for an account of their social situations along with their academic records." After being rebuffed in this request, as part of his findings, the judge assailed the Kentucky Welfare Commissioner, Luther T. Goheen, saying his attitude "spells antagonism and provincialism tantamount to obstruction of justice." ("Judge's Blast at Welfare Chief Rapped", Lexington Herald, April 30, 1952.)

With the news of Judge Streit's charges, the University did request that third-parties come and investigate, including the SEC and the NCAA.

As to the specifics of the case, the University took a few days to formulate any type of official response. Said university Vice President Dr. Leo Chamberlain "[Judge Streit had] four months in which to prepare his statement," he thought the University should be afforded a few days to respond.

Many of Rupp's former players came to his defense. Ten players on the 1951-52 squad signed a statement later in the week after Streit's findings that stated that "we want absolutely to deny that Coach Rupp ever in our presence has committed any act that would in any way corrupt us." (Associated Press, May 3, 1952. The players were Cliff Hagan, Bobby Watson, Shelby Linville, Frank Ramsey, Gene Neff, Charlie Keller, Lou Tsioropoulos, Skippy Whitaker, Gayle Rose and Willie Rouse)

Fifteen former players signed a statement after the scandals broke which denied and took issue with Streit's claims. In part the letter stated "We feel that Coach Rupp at all times sought to have us conduct ourselves as to be a credit to the University and to make us better citizens." It went on to state, "the charge of Judge Streit that Coach Rupp deliberately sacrificed the physical health and well-being of his players is also untrue as far as we have ever seen or known of. On the contrary, Coach Rupp was very zealous in safe-guarding the physical health and welfare of the basketball players during all the years we were on the squad." (Lexington Herald Leader May 11, 1952. The players were "Little" Louis McGinnis, Crittenden Blair, C.J. "Jake" Bronston, William Kleiser, David Lawrence, Harry Denham, Cecil Bell, Ralph Carlisle, Ellis Johnson, Carl Combs, Rudy Yessin, Kenneth Rollins, Wallace Jones, C.M. Newton and team manager Humzey Yessin.)

Kentucky did respond to Streit's ruling in a five-page response [which can be found here (1) (2) (3) (4) (5)] in which they addressed each of Streit's most serious charges. The University did take partial responsibility and admitted wrongdoing in some cases, however it was noted numerous times where the Judge had either came to conclusions based on a poor understanding of the facts, or chose to assume the worst of a situation in order to promote his own agenda. The University defended its use of athletic scholarships, which had been a well established system (and in fact is still in use today) despite Judge Streit's personal belief that they were illegal. The University also took issue with the judge overstepping his jurisdiction by trying to dictate how their athletic programs should be run. Wrote the group, "We shall be answerable to the people of Kentucky, to the NCAA and our regional association . . . our policy will not be dictated by Judge Streit."

Regarding the charges of consorting with Ed Curd, Rupp admitted that he did know Curd socially, and had at least once called on him to solicit donations for the local Shriners Hospital, which Rupp was instrumental in having built. But he adamantly denied taking part in any betting on basketball games, and in fact Rupp had on many occasions publicly campaigned against such practices, and criticized newspapers for printing point spreads.

Streit had also claimed that Curd had provided a team dinner at the Copacabana Club in New York City. While Kentucky officials acknowledged that Curd was present, it was disputed that Curd paid for the meal. Said Athletic Director Bernie Shively, "That judge did his best to put Adolph as far behind the eight-ball as he could. He said that Ed Curd had picked up a big check for a players' night out at the Copacabana. Well, it just happened that I was along and I paid the bill out of our travel expenses. I've had several photostats made of it and I always carry it around in my wallet." ("The Life and Battles of Adolph Rupp," by Furman Bisher Sport Magazine March 1959.)

The day Streit's charges were revealed, former player and friend of Rupp Burgess Carey was asked about the reputed $500 bet he lost. Carey laughed at the claim, "That beats anything I ever heard. . . There's some gross exaggeration somewhere along the line. I rarely bet, and when I do it's for small amounts. No, no, it's not for anywhere near $500." ("Ex-Wildcats Get Suspended Sentences; Judge Assails Rupp", Lexington Herald, April 30, 1952.)

JPS Note: It seems apparent that Streit literally believed everything that the players told him during their testimony had an actual basis of fact. What was not taken into account was that most of this information was second hand, and coaches often exaggerated for effect, in order to motivate their teams.

Rupp in particular was known as a master motivator of players who often stated things with only a passing connection to reality. If he told a player that his missed shot cost his friend $500, the amount was likely put there for effect. It may not have even been true that a bet was lost at all. The point to Rupp was that he was trying to impress upon his player the importance of not missing shots. Whether what Rupp told his players was actually true or not was more often than not irrelevant.

This type of context that Rupp often worked in was apparently completely lost on Judge Streit. Perhaps if the Judge had listened to more direct testimony (rather than relying so heavily and apparently literally believing second-hand information) and perhaps if the testimony had been properly fleshed out under scrutiny from a defense counsel, then maybe the judge wouldn't have been so apt to put stock into so many questionable claims.

|

Rupp adamantly denied any knowledge of point shaving by his players, and in fact no evidence was ever produced to show that Rupp had relevant ties to gambling. He also disputed the idea held by some that Kentucky attracted talent to their program illegally through inducements etc. Noted Rupp sarcastically many years later, about the idea "Look at some of my boys. They come from Versailles or Paris or Louisville. It takes a lot of recruiting to get a boy from 20 miles away to come to his own state school, doesn't it ? I think you'll find there aren't any boys in school who come from eight states away because of my grand personality . . . like they do in other schools." (Sport Magazine "Kentucky Apologizes for Nothing!" by Jimmy Breslin, March 1953)

JPS Note: The fact of the matter is that when you look at UK's teams, it is true that the large majority of the players came from local areas. And even the players who came from out of state involved a certain element of luck. For example, Alex Groza only came to Kentucky after Ohio State turned him down (despite being the younger brother of OSU football legend Lou Groza). Lou Tsioropoulos came to Kentucky on a lark after stopping by Lexington on the way to an All-Star football game and deciding to give basketball a try.

Kentucky did indeed hold distinct advantages, in that they offered athletic scholarships at a time when many other schools failed to do so. Kentucky also offered players the opportunity to compete at the highest levels and travel nationally, another aspect of the basketball program that other schools simply couldn't (or wouldn't) match.

As far as Rupp's knowledge of his players shaving points, it is noteworthy that in Nick Englisis' magazine article (True Magazine, 1952) he clearly states that he and his associates took particular care to stay out of sight of the coaching staff (i.e. only meeting the players off-campus etc.)

The welfare of the players was a curious situation as it demonstrated how far apart Streit's views were from reality. After the request came from New York asking that a investigation be made of the welfare of the players, Kentucky welfare officials tried to explain to the courts that they had no authority to conduct such an investigation, explaining that their authority was over delinquent children (with children being defined as those under the age of 17) who had been turned over to them by the courts. Beyond that, their department was limited to mental health and penal cases within the state. None of these circumstances matched the players in question in any way.

Kentucky Welfare officials thought that perhaps the judge was unfamiliar with Kentucky law, and offered that perhaps New York law had such authority. In fact the two agencies were different. None of this reality seemed to prevent the judge from haranguing Kentucky welfare officials for what he called "antagonism and provincialism, tantamount to obstruction of justice."

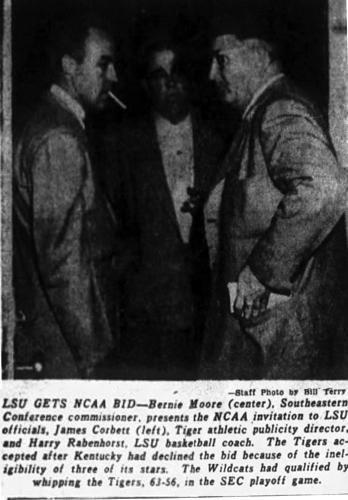

A few weeks after Judge Streit's decision was made public, the Southeastern Conference announced that they would investigate the University of Kentucky athletic programs, something UK had already proposed. Bernie Moore was the former head football coach at Louisiana State University prior to becoming SEC Commissioner in 1948. Said Commissioner Moore concerning the Kentucky situation, "We waited until the court action in New York was over." (United Press, May 19, 1952). Moore promised a "complete and thorough investigation" into Streit's allegations.

The investigation dragged on through the summer of 1952. In late July, legendary Atlanta Journal sports columnist Ed Danforth in his column suggested that Adolph Rupp stepping down would solve the issue, as the charges could be dropped and the SEC members wouldn't have to worry about setting a precedent which they themselves could easily fall victim to.

Taking Dr. Gallalee's invitation to draw conclusions, this column whips up a fast sketch of the picture.

Why, Dr. Mike Denny of Alabama INVENTED recruiting and subsidizing. Tennessee took up the idea and did a better job of it. Georgia has done right well in covering the Eastern seaboard. Florida's fund for assisting athletes is fattened each year by a cut from the gambling profits of horse and dog tracks. The SEC executive committee may have realized they would look funny suspending Kentucky from the organization for doing nothing more than making a success and showing a profit on the established system. Kentucky's chief offense so far is success at operating a delicately balanced group athletic policy. It is entirely possible that nothing is out of line at Kentucky except Adolph Rupp and his basketball policies. He won too many games and his operation made too much money to be healthy. Few people can stand prosperity and no basketball players and coach, you might say. Only the too successful ones fell into the hands of the gamblers. Rupp could clear up the whole matter by resigning. Chances are then the charges against Kentucky would be dropped. The university with an old-fashioned sense of justice has refused to repudiate Rupp because he was doing what they wanted: win games at no cost to the taxpayers. . . The only quick solution would be for Rupp to resign for the good of the order and go back to his registered cattle to live in peace as he has been advised to do by his physicians. (by Ed Danforth, Atlanta Journal, "Conference Presidents Have Hot Potato In Investigating Kentucky Operations," July 30, 1952.) |

|

Reportedly the decision with regard to the basketball team had been made earlier during a July 28 meeting of the executive committee, under which the school was to be banned from playing any games. However that decision was deferred until further investigation could be completed, some of it done personally by SEC Commissioner Bernie Moore. After the August meeting, the more lenient penalty was announced, which allowed Kentucky to play games outside of the conference. Moore himself specifically mentioned this aspect of the ruling when it was made public. (Lexington Herald, "UK Suspended from SEC Basketball For One Year" August 12, 1952) According to the article, "Moore said there will be no fines in connection with the suspension in basketball. He pointed out that Kentucky can still play non-conference games - a phase that has made most of Kentucky's headlines since it became a national basketball power a decade ago."

The university had the right to appeal the penalties, but under the guidance of UK President H.L. Donovan, the school chose to accept the SEC ruling as-is. While acknowledging that UK had broken rules, Donovan did express his objection to the severity of the penalty. Said Donovan, "We were impressed with the integrity and the sincerity of the executive committee in their long and exhaustive deliberations. Nevertheless, we feel the punishment we have received is excessive for the violations with which we have been charged and which we have confessed and which have been committed by other members of the SEC in recent years." (United Press, August 12, 1952).

The one interesting aspect of the SEC's decision was they failed to actually say what the charges against Kentucky were. "we tried to get them to spell out the charges and they wouldn't do it." noted President Donovan when asked by reporters.

The decision by the SEC was met with varied reaction in the Commonwealth and the South. "If you can't beat'em, suspend 'em." wrote Lexington Herald sports editor Ed Ashford to sum up how he thought the SEC's proceedings went. While some sportswriters thought Kentucky got what they deserved, many acknowledged that the charges against Kentucky could have applied to any other SEC school, the very ones sitting in judgement.

|  |

On February 22, 1953, it was announced that Michigan State had been put on probation for a year due to the reporting of the "Spartan Foundation of Lansing" which had illegally given monies to Michigan State individual athletes on the order of approximately $3800.

The Herald's Ed Ashford once again commented on the disparity between the way the SEC dealt with UK against the way the Michigan State case was handled.

Kentucky, accused of giving its basketball players $50 expense money for several days in New Orleans during Sugar Bowl festivities, was suspended one year from basketball competition by the SEC. The NCAA followed this verdict by putting UK on probation for a year and requesting other NCAA teams not to play the Wildcat cagers. It amounted to at least $100,000 to the UK athletic treasury.

Yesterday, the Big Ten meted out punishment to Michigan State, whose alumni reportedly had raised a huge fund to aid athletes and had paid out several thousand dollars to athletes.

The penalty: Probation for a year. But Michigan State can play schedules in all sports and will be eligible for Big Ten and NCAA championships! Figure it out yourself, I can't." - by Ed Ashford, Lexington Herald, February 23, 1953.

Sidebar: Walter Byers and the NCAA The 1951 Scandal marked the ascendency of the NCAA as an organization for the most part capable of policing itself. In the years leading up to the Scandal, the organization had adopted the "Sanity Code" under which the respective schools policed themselves. The "Sanity Code" was an attempt to limit the burgeoning athletic enterprises that were growing up around the country, by defining and limiting recruiting, athletic scholarships and academic requirements. The entire issue of athletic scholarships was a contentious one, as some schools did not utilize them and viewed them as illegal, while other schools (including many of the big schools in the South and Midwest) saw athletic scholarships as a model and cornerstone for their athletic programs. In 1950, seven schools (Maryland, the Citadel, VMI, VPI, Villanova, Virginia and Boston College) which had revealed that they had violated aspects of the Sanity code, stood in judgement. The NCAA convention of 1950 voted 111 to 93 to banish the teams from membership. However, a two-thirds majority was required which was not attainable, and no sanctions were levied. The Sanity Code was dealt a severe blow. It was formally repealed the following year.

Under a backdrop of revelations of point shaving and dumping games coming out of New York, the NCAA in January of 1952 authorized a Membership Committee which examined complaints and a subcommittee (the Subcommittee on Infractions) to investigate as warranted. The findings of investigations would be reported to the NCAA Council which had the power to suspend or place members on probation. As it happened, soon after the organization was established and Byers was installed as the NCAA first Executive Director, the news of Kentucky's involvement became public through Judge Streit's rebuke of the University. Kentucky became Case Report No. 1 for Byers and the NCAA. The reputation of the fledgling organization and it's new subcommittee would be put to a test with the case against Kentucky. Failure would have left the organization and it's new structure still-born. In light of the failure of the Sanity Code, this could have proven the death knell of the organization itself. Wrote Byers in his memoirs: "Had they (UK) fought us on the technical, legal grounds so many university-hired lawyers used in later years, Kentucky probably would have carried the day at the convention in January 1953. Instead, their decision to accept the penalty erased the haunting failure of the Sanity Code. It gave a new and needed legitimacy to the NCAA's fledgling effort to police big-time college sports." (Unsportsmanlike Conduct, pp. 60-61.) As mentioned by Byers himself, Kentucky's decision to abide by the NCAA's ruling without appeal gave the NCAA (and by extension Byers and his office) needed credibility. This set the stage for the continued growth and authority of the NCAA which we see today, for better or worse. |

Although it was never publicly announced by the school, the schedule was to include games against "Illinois Wesleyan, Minnesota, Virginia Tech, Bowling Green, Springfield Mass. College, Miami Fla., Florida State, St. Louis, St. Bonaventure, Notre Dame, Gustavus Adolphus and two games each with Xavier of Cincinnati, DePaul, Temple, Loyola of Chicago and Wyoming." (Associated Press, November 4, 1952)

But the NCAA had other ideas. When Streit's pronouncements concerning UK were first made public earlier in the year, the NCAA had announced their intention to investigate and requested an inquiry into the athletic policies and practices at the school by the Infractions Subcommittee. This subcommittee, which was a part of the Membership Committee, had just months earlier (in light of the transgressions revealed by LIU and CCNY among others) been authorized to investigate non-compliance of NCAA rules. But with the SEC stepping in and announcing their own investigation, the NCAA seemed to take a back seat.

After the SEC announced their findings in August, the NCAA had yet to announce any sanctions of their own. Lexington Herald sports editor Ed Ashford noted the silence and in light of preparations for the season being underway along with a move of the NCAA headquarters from Chicago to Kansas City, it was noted that the NCAA had appeared to miss their opportunity with Kentucky.

Wrote Ashford in a September 16 article, "When Sept. 1 passed without the University being notified of the NCAA's intention of either terminating or suspending Kentucky's membership or otherwise disciplining the University, it meant that the association, under its constitution, can take no action on Kentucky at its annual convention next January." Ashford cited Section 6 of Article IV of the constitution which stated that membership votes had to take place at the annual Convention (held in January). In other words by the NCAA's own regulations, they would not be in a position to rule on Kentucky's fate until after the basketball season had already begun.

But the NCAA had another line of attack. With SEC Commissioner Bernie Moore working behind the scenes with NCAA executive director Walter Byers, the two were hatching a plan. Rather than go through the formal process of banishing Kentucky, the NCAA opted instead to threaten the rest of the membership to not schedule the Wildcats that season.

Wrote Byers in his NCAA memoir (Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletics, University of Michigan Press, 1995):

|

Bernie [Moore] and I concluded, however, that terminating Kentucky's NCAA membership was not necessary. Our enforcement committee cobbled together a custom-made boycott, based on a constitutional provision that members had agreed to play games only with colleges that abide by NCAA rules.

Kentucky representatives, A.D. (Ab) Kirwan and Leo Chamberlain, did not cover up. They didn't need high-powered attorneys to speak for them. Unlike SMU officials three decades later, they didn't attack the 'system' or the NCAA. They stood before the committee and the NCAA Council telling the truth as they knew it. Ab Kirwan later became my good friend and an outstanding chairman of the NCAA Infractions Committee. He served the University of Kentucky at various times as a history professor, head football coach, and acting president. To me he represented the best attitudes of chivalry and intellectual pursuit. I telephoned Ab and Leo Chamberlain in their hotel room to tell them first of our admiration for their openness and integrity, then of the committee's verdict: cancellation of all intercollegiate basketball at Kentucky for an entire year. Ab later told me how he and Chamberlain packed their suitcases in stunned silence and entered a taxi for the ride to the train station. Shocked and struggling to recover his humor, Chamberlain turned to his companion and said: "If we hadn't been so forthright and made such a good impression, Ab, I wonder what the penalty would have been ?" (JPS Note: The term 'death penalty' is used loosely by Byers in these memoirs in that the term did not exist at the time and the punishment Kentucky received was not nearly the same severity as the 'Death Penalty' which was devised decades later in the 1980s to deter schools from becoming repeat offenders. In the latter case, the Death Penalty called for the sports program to be disbanded completely, which in reality meant the coaches were fired, players dispersed etc. None of this happened at Kentucky. This fact has not deterred some from erroneously stating the Kentucky received the first death penalty.) |

The specific charges levied against Kentucky by the NCAA were:

As with the Southeastern Conference ban, President Donovan chose to accept the NCAA's punishment without appeal. This was significant because as Byer's himself admitted, Kentucky had every right to appeal the decision (a decision which Byers himself described as 'shaky'), which would have been addressed at the January convention at which point it was likely the ruling would have been overturned by the membership. Given that the basketball season started in early December, a delay until January of the following year would have allowed Kentucky to begin and likely complete their season.

|

Similar to the reaction after the SEC decision, the response to the NCAA decision (at least from those knowledgeable in big-time college athletics at the time and honest enough to discuss it openly) noted the hypocrisy of the ruling. (see article to the right).

Wrote Arch Ward of the Chicago Tribune, "We make no defense of any university which professes to live up to the rules of the unit to which it belongs and then violates them willfully . . . But the NCAA council knows that its disclosures of the $25 and $50 gifts received by Kentucky basketball players, from outside the school or within, was peanuts. . . Many universities whose athletic prominence equals or excels Kentucky's would be placed on probation, as has Kentucky, if penalties were applied generally. . .Comparable violations occur in groups which supposedly are models of all that is good and holy in athletic administration . ."

Ed Danforth of the Atlanta Journal noted "If every athlete in the nation who has been given such assistance by fans were disqualified, the boys would have a hard time fielding teams for the coming week end."

Pat Harmon of the Cincinnati Post wrote: "It's a laugh. Certainly Kentucky is guilty of permitting its athletes to accept side payments, but so is almost every other member of the NCAA. It's been going on for years. The writer has been present when cash payments were made to athletes at a Big Ten school."

Of particular interest were the comments of Tom Easterling, the sports editor of the UK student newspaper The Kentucky Kernel. He maintained that the SEC Commissioner, Bernie Moore, had assured Dean Ab Kirwan that he would go before the NCAA Council to urge them not to take additional action against Kentucky, beyond what the SEC had already given. Noted Easterling, "Moore, a member of the executive committee, was in Chicago at the same time the council was acting on the UK case, but he never made an appearance before the council, as he had promised to do." (see article to right).

Not only didn't Moore plead on behalf of Kentucky, but per Byers own memoirs (see above) it was Moore who was the driving force behind the NCAA's further actions against the school. Moore was in actuality secretly back-stabbing Kentucky while professing to be working in the school's best interest!

In an article a few weeks later, UK Alumni Association President Bill Gant noted that earlier that summer when the SEC was investigating, Moore "never examined the files at the University of Kentucky when he came to make his investigation. It seems he had his mind made up before he arrived." (Louisville Courier-Journal December 5, 1952).

As with the SEC ruling and Judge Streit before him, while President Donovan did admit that wrongdoing had occurred, he did take issue with some of the particular findings and the overall harshness of the punishment. "It is the opinion of our athletics board that the penalty inflicted upon the University of Kentucky is unduly severe and far more harsh than any penalty that has ever been inflicted upon a member for violation of the NCAA rules in the past." wrote Donovan to NCAA President Hugh C. Willett (Associated Press in Charleston (WV) Gazette Kentucky Cancels Season's Basketball Card November 4, 1952.)

With the announcement, once again the University investigated Coach Rupp and his role in the affair. The findings were that the UK coach "did not knowingly violate the athletic rules." UK President Herman Donovan also found that Rupp had not committed a breach of ethics. "If I thought otherwise, I would have dismissed him, " stated Donovan (The Rupp Years by Tev Laudeman, 1972)

Regarding the monies given to players after the Sugar Bowl appearances, Donovan said "I and other university officials knew about and approved the $50 given to basketball players, after two appearances in the Sugar Bowl. When we first appeared in football bowls we learned that it was customary among all schools going to bowls to give their players extraordinary expense money.

When we went to the Orange Bowl, we asked the Southeastern Conference about the expense money and were told we could award each player $200. When we went to the Sugar bowl, we received permission to give the players $250.

From that we reasoned it also would be within the rules to award basketball players $50 expense money after the Sugar Bowl basketball tournaments." (quotes from The Rupp Years, Tev Laudeman, 1972).

Although it was generally acknowledged that if UK had cut Rupp loose and forced him to resign, that the sanctions on UK would be have significantly lighter, Kentucky chose to stick with their coach.

Said Donovan about Rupp, which cut to the heart of the issue "Adolph Rupp is an arrogant man, given to sharp repartee and cutting sarcasm. He is awkward in public relations and a genius for saying the wrong thing. He also happens to be the best basketball coach in America. This last qualification also figured strongly in what later happened to us." (reported in Atlanta Journal and Constitution December 17, 1952.)

In fact, the scandal provoked a turn of events as Rupp was seriously considering retirement at the time due in large part to health problems, but the scandal caused him to have a change of heart and decide that it was best for him to stay and deal with the "shelling", rather than hand it off to someone else. (Associated Press, December 28, 1951).

As the fall-out continued, Rupp became more and more focused on his goals. No longer was he merely trying to be the most successful coach in the nation, Rupp was now also looking to prove his critics wrong in dramatic fashion. Rupp was especially bitter toward the head of the NCAA at the time, Walter Byers. He vowed "I'll not retire until the man who said Kentucky can't play in the NCAA hands me the national championship trophy." (Big Blue Machine, Strode Publishers (1978), pg. 234.) Rupp had to wait until the 1958 Fiddlin' Five squad make good his vow, but he was true to his word.

|

"I'm doing more coaching now than I ever did." boasted Rupp. "In the ordinary season the practice schedule goes like this: Monday, game; Tuesday, off; Wednesday, fundamentals; Thursday, scrimmage; Friday, look at your opponents' style and design a defense; Saturday, game; Sunday, you may get an hour to go over your defense for the team you're playing Monday."

"There's a lot of lost time in a schedule like that, and you have to keep it in balance - so much offense and so much defense."

"But the schedule we use now doesn't lose any time. If we start to work on a certain play, we go until we're satisfied. We don't have to quit when we're half-satisfied, so we can start on something else. We work 90 minutes on one play if we want to."

To break up the monotony, four scrimmages were held that year and each was sold out, save one which occurred on an icy night. Despite the weather over 6000 souls made it to Memorial Coliseum to watch. Regarding the other three contests "We had three of the biggest crowds in the South," said Frank Ramsey ("It's 50 years since the season that never was" by C. Ray Hall, Louisville Courier-Journal December 26, 2002.)

| Date | Game | Attendance |

|---|---|---|

| 12/13/1952 | Varsity 76, Freshmen 45 | 6,500 |

| 1/19/1953 | Ramsey's 71, Hagan's 50 | 9,000 |

| 2/4/1953 | Hagan's 68, Ramsey's 55 | 10,000 |

| 2/28/1953 | Blues 49, Whites 47 | 9,000 |

The players stayed loyal to their wounded coach. Despite Cliff Hagan, Frank Ramsey and Lou Tsioropoulos all being drafted by the Boston Celtics in 1953, they all chose to remain with UK in order to win a national championship. (According to Assistant Coach Harry Lancaster in his book Adolph Rupp As I Knew Him, the Celtics tried to convince Ramsey to turn pro that season but Lancaster talked Ramsey out of it.) They dropped credits to remain eligible for the following season.

As for the Southeastern Conference, Harry Rabenhorst's LSU team was the class of the conference. They finished the regular season conference slate with a perfect 13-0 record, led by All-American Bob Pettit.

Fortuitously for the league, the 1953 SEC tournament (a tournament that Kentucky dominated and for the previous twelve years had been held in Louisville, KY, which allowed for record crowds) had been cancelled previously during the December 1951 Conference Annual Meeting.

The decision to cancel the tournament was influenced by a generalized effort nationally towards deemphasis of athletics (not including football where the sanctity of post-season bowl games was kept intact by the SEC members) although it's not out of the question that league members were simply tired of Kentucky dominating the event when they cast their ballots.

Canceling the basketball tournament averted what likely would have been a dismal turnout with Kentucky not in the mix. Instead of a tournament champion, the regular season league champion was named as the NCAA tournament representative. The SEC tournament would not be revived until over 25 years later.

For the first time in history, a team from the Southeastern Conference (other than Kentucky) represented the district in the NCAA tournament. Louisiana State was that representative and went on to win their first two games in the tournament, which put them in the Final Four. The Tigers then lost to Indiana in the semi-finals and finished fourth overall after losing the consolation game also.

|

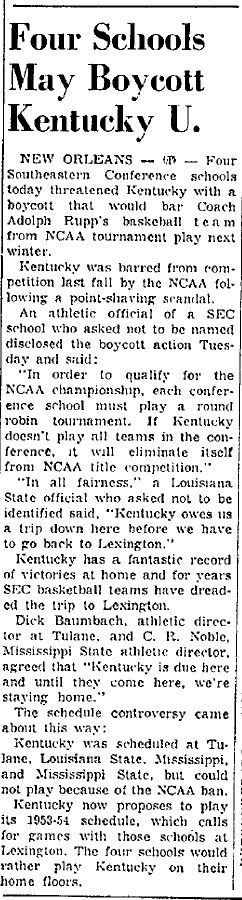

Their old friends the LSU Tigers (and three other schools) threatened to boycott playing Kentucky if the Wildcats didn't travel to their campus for the regular-season game instead of holding the game in Lexington. (and also hinting that failure to comply would result in UK not being eligible for the NCAA tournament for yet another season.) "It's bad enough we had to sit out a year, but now they want us to spend the next season as a traveling team," complained Rupp. (Sport Magazine, January 1954).

The point of contention was that in the 1951-52 season LSU faced UK in Lexington, a game Kentucky won by 10 points. Normally the game location would be alternated each year, meaning UK would have travelled to Baton Rouge in 1952-53. However with UK sitting out the season, such a return game did not occur.

Kentucky assumed that the 1953-54 season would see the series picked back up as it was originally envisioned, with LSU coming to Lexington. LSU balked at this proposal, insisting the Wildcats still owed them a home game. "In all fairness Kentucky owes us a trip down here before we have to go back to Lexington." said an unnamed LSU official (see article to right), conveniently ignoring the fact that it was LSU and most of the other SEC schools that voted to prevent UK from playing its original schedule in the first place.

Not surprisingly, the schools (Florida, Alabama and Auburn) which had hosted UK on their respective campuses in 1951-52 and were set to host UK again were not looking to upset the status quo. [Vanderbilt, Tennessee and Georgia Tech had all faced UK both home and away so the issue was moot to them.]

In the end, the conference schools convened and voted in favor of retaining the original status quo, and the other three schools (Tulane, Mississippi and Mississippi State) did return to Lexington for their thrashings. LSU, adamant to the end, ignored the conference vote and chose not to face Kentucky in the regular season. For their part, Kentucky acquiesced, noting that they could not force a team to play them if they didn't want to. This seemingly minor detail would prove important and ended up having to be dealt with at a later date.

The other lingering point of contention dealt with the eligibility of UK's three returning seniors (Cliff Hagan, Frank Ramsey and Lou Tsioropoulos), who formed the core of their squad. Since the three either had already graduated (or were due to graduate before the spring semester) and were finishing their basketball eligibility as graduate students, they were technically not able to compete in the NCAA tournament according to a rule on the books at the time (although they were still eligible to compete in the regular season).

Prior to the start of the season, Dean Ab Kirwan of the University asked that the NCAA eligibility committee review the three players' situations to ensure that they were indeed eligible for the coming year and to clear them of any association with the alleged transgressions which had placed Kentucky on probation. The NCAA did look into the issue and did exonerate the current Kentucky players of any such connection and confirmed their eligibility to participate in the coming year. With the ruling in hand, Kentucky looked forward to the new season.

However one detail that was missed was uncovered by Larry Boeck of the Louisville Courier-Journal when he wrote an article in (January 26, 1954) [Links to Page 1 and Page 2] which noted that due to the rule on the books, the Kentucky players "apparently will be ineligible for the NCAA basketball tournament." This caught Kentucky officials off-guard as they had believed the earlier ruling by the NCAA had covered the player's eligibility for post-season play.

Kentucky Athletic Director Bernie Shively noted that the University intended to appeal the rule in the event Kentucky earned a post-season berth.

Although NCAA regulations state that no waiver can be granted in the eligibility rules governing its post season tournaments and title meets, Shively said that an appeal definitely would be entered if Kentucky gained a place in the basketball play-offs.

He expressed the opinion that the case of the Kentucky seniors could merit special consideration because of extenuating circumstances, mentioning the basketball suspension imposed against the school last season and the "penalty" thus imposed upon the players through no fault of their own.

Shively pointed out that conference regulations require athletes to carry a normal load of school work each semester, and pass a specified number of their courses, in order to be eligible for athletics, and that the "normal progress" made by the Kentucky cagers thus advances them to graduate status before they have been allowed to complete the collegiate competition to which they are entitled.

(Excerpted from "U.K. to Request NCAA Waiver for Seniors If Play-Offs Gained," Lexington Leader, January 26, 1954.)

When SEC Commissioner Bernie Moore was asked about the situation, he was reluctant to comment.

Moore, reflecting on the SEC eligibility wrinkle which has permitted legal play by three Kentucky basketball aces who may nevertheless, be barred from play in the NCAA championships, said he could not comment on the 'equity' of the rule.

He said: "That's a matter for the administrators of our member schools to comment on. It's not my position to do so."

Moore said he could not comment on the statement by Kentucky cage coach Adolph Rupp that graduates have played in the NCAA's tourneys before, but said:

"As far as I know, the number of graduate students who have played in the SEC is not large. I doubt very much that they could be numbered in the hundreds or anything like the hundreds."

(Excerpted from "No Grad Cagers Remembered," (INS) in Kingsport (TN) Times, January 28, 1954.)

With a year of dedicated practice under their belt, the 1953-54 team came out with a vengeance. Rupp was still angry, and reportedly boasted that "We have a new scoreboard that can register beyond 100 points, so we'll score half for the season we missed and half for this season."

"They'll be no point shaving this year," said Rupp. "When we run up one of those 95 or 97-point totals - and we used to do it often - and there's still a couple of minutes to play, I'm not going to pull my boys up and have them stand around at midcourt and try to hold the score down so we don't humiliate somebody. We'll just keep playing our game and let the other guy worry." (by Jimmy Breslin (NEA), December 14, 1953).

As it turned out, the Wildcats did put the scoreboard to full use three times at Memorial that year.

|

When Tulane came to campus, Kentucky was 10-0. Rupp posted newspaper clippings before the game that told how Tulane had voted to suspend the Wildcats. Pointing to opposing coach Cliff Wells, he told his players, "He's on the floor now, the man that led the fight against you last year. For ever blister, every bruise, every black eye, every tooth knocked out last year, that little runt of a coach owes you. Tonight you pay them back for all of last year." The Wildcats defeated Tulane 94-43 and won the remaining thirteen games on their schedule. - by Russell Rice, Adolph Rupp: Kentucky's Basketball Baron, Sagamore (1994), pg. 135.

The 1953-54 team would have had an excellent shot at winning the title, going 25-0 and beating the eventual champion LaSalle by a convincing 73-60 margin. Kentucky was an undefeated 14-0 in the conference regular season, but so was their nemesis Louisiana State. A playoff game was called for to be held in Nashville to settle the issue.

As mentioned, there also was the lingering issue of whether the three seniors would be eligible for the NCAA tournament, a subject the NCAA had been eerily silent about. Only after it became imminent that an NCAA bid was due was the formal appeal submitted. The team didn't hear back from the NCAA until after they had secured the SEC Championship with a 63-56 win in an SEC play-off game over LSU. As the players were celebrating their victory in the locker-room, the NCAA threw cold water on the party when it declared that the rule stood and the players weren't eligible for the NCAA Tournament.

|

"We were penalized for the year we were forced to sit out and that was for something we had not been involved in. If we had taken five years to graduate we wouldn't have had a problem. So we were penalized for trying to do the right thing. Isn't that something ?" - by Bert Nelli, The Winning Tradition, University Press of Kentucky (1998), pg. 73.

Postscript: One final bit of housekeeping which didn't get settled until years later occurred when Kentucky began the 1955-56 season by travelling to Baton Rouge to play a "non-SEC" game against the Tigers. This did not count in the official SEC Standings but was done to give LSU the home date against the Wildcats that they believed they had lost. Kentucky won the game 62-52 over LSU and coach Harry Rabenhorst.

|  |

The experience of the scandal scarred Rupp for the rest of his life. He vowed to never take one of his teams back to New York City and made good on that vow. Only years after his retirement in 1976 did Rupp again set foot in the Big Apple, when a Joe B. Hall-led team competed in the now-down trodden NIT and Rupp accompanied the team. Even after 25 years, the elderly coach was still visibly agitated when asked about the scandal by a New York Times correspondant. "People told me I should have known what was going on," said Rupp. "Hell, we won the N.C.A.A. and the the N.I.T. and we sent the team to the Olympics with those players. If I was supposed to know what was going on when a team like that is winning, then why doesn't a coach of a losing team think his players are fixing games ?" ("Kentucky's Baron Still Holding Court," by Gerald Eskenazi, The New York Times, March 14, 1976.)

Sidebar: Adolph Rupp and his tongue Adolph Rupp was a colorful character who was often-time quoted throughout his career. Newspapermen were known to flock to him looking for a memorable quote and more often than not Rupp obliged. The scandals in the early 1950's saw Rupp make a number of comments that later would come back to hurt him in the public's eye. Said UK President Herman Donovan about his coach, "Adolph Rupp is an arrogant man, given to sharp repartee and cutting sarcasm. He is awkward in public relations and a genius for saying the wrong thing." (Atlanta Journal and Constitution December 17, 1952.)