![]()

![]()

| Introduction | Early Beginnings | The Organizers | The Sponsor | The Accommodations | The Arena | The Format | The Media | The First Official Tournament | S.I.A.A. to Southern Conference | Rivalries | The Officials | Changes to the Game | Technical Advancements | Stars Shine | The Coaches | Committees | Breakup of the Conference | Legacy |

![]()

The Southern Intercollegiate Athletic Association's (S.I.A.A.) basketball tournament in Atlanta was one of the very first conference post-season basketball tournaments ever held in the United States. It was also likely the largest of its kind and became a showcase for basketball in the South.

Teams from Maryland to Louisiana participated in the tournament, which was held in the Atlanta Auditorium. During the time period between 1921 (when the first Southern tournament was held) until 1932 (when many of the teams from the Western side of the conference announced the formation of the Southeastern Conference), thirty-six colleges and universities saw action in the event. And during this time the big winner was the University of North Carolina, who won the title four times (1922, 1924, 1925 and 1926). The Tar Heels sported a nearly 79% winning percentage in tournament play.

Every other year, a different team won the title. This included Kentucky (1921), Mississippi A.&M. [now Mississippi State] (1923), Vanderbilt (1927), Mississippi (1928), North Carolina State (1929), Alabama (1930), Maryland (1931) and Atlanta-favorite Georgia (1932).

Although the schools were in name part of the same organization (initially the S.I.A.A. and later exclusively the Southern Conference), it was not practical to determine a true conference champion in the regular season. This was due to the fact that there were so many schools that it was impossible to face them all during the season, even without considering the huge geographic reach of the conference footprint.

The tournament was selective in who was invited, and which applications were accepted, based on their perceived strength during the regular season. Furthermore, the tournament provided a means for teams from far across the geographic footprint of the conference to face each other on the court, in order to determine an undisputed champion. Whoever came out on top could rightly call themselves "Champions of the South", particularly in the early years when both the Southern Conference and the remaining members of the S.I.A.A. participated in the tournament.

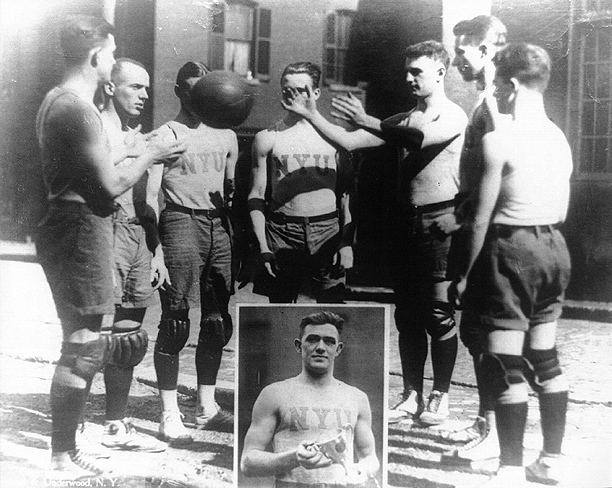

Prior to the S.I.A.A.'s inaugural tournament in 1921, it was actually preceded the year before when New York University won the national A.A.U. title in an event held in Atlanta in March of 1920. The NYU Violets beat the Houston Y.M.C.A., the Los Angeles Athletic Club, the Kansas City Athletic Club and Rutgers University in the championship game.

Wrote Georgia Coach H.J. Stegeman about the A.A.U. tournament and it's importance and potential effect on Southern basketball:

"This tournament was the first that had ever been held in the South and proved to be a blessing for basket ball in this section of the country, though none of the Southern teams survived after the second day of play. On account of the infrequency of games between Northern and Southern teams, basket ball in the South has never readied the stage of perfection with which it is played in the North, East and West. The fact that a brand of basket ball, much faster than ever was seen in the South before, can be played with a minimum of bodily contact, was an eye-opener to all spectators and many Southern players, and this lesson should last for a long time. The fast dribbling game of the Northern teams proved to be immensely popular with the large crowds that attended all games, and the fast pivoting and dodging of such men as Cann of New York University and Dermody of Detroit drew continued applause, attesting the fact that Southern fans were soon converted to this style of play." - ("Review of the A.A.U. Season, 1919-20," by H.J. Stegeman, Spalding Official Basket Ball Guide, 1920-21.)

|

Most Valuable Player for the Violets was Howard Cann, who in 1923 became the head coach of his alma mater where he went on to a long and successful career, with a 429-235 record over a career that spanned from 1923 to 1958. The coach of the NYU team was Ed Thorp, who had been hired a few months earlier. Thorp would go on to become an official, and would work the Atlanta tournament, as did his brother Tom.

In December 1920, Atlanta Constitution sports editor Cliff Wheatley noted that during the annual S.I.A.A. conference meeting, held in Gainesville, FL, that plans were being made to sanction a basketball tournament. Noted Wheatley:

"One piece of positive legislation enacted was the authorization of a S.I.A.A. basketball tournament to be held in Atlanta during March. Definite arrangements for this tournament were put in the hands of a committee. It is believed that it will be staged in the Auditorium-Armory." - ("Conference Meeting in Spring Will Decide Important Issues,", by Cliff Wheatley, Atlanta Constitution December 14, 1920.)

Further elaboration of the origins and meaning of the tournament were discussed the following month in the Atlanta Constitution:

"This meet will be of prime importance in that it will determine decisively the holder of the S.I.A.A championship honors. In previous years, there has been no way to judge the champions of the south in the south is best entitled to the basis of comparative scores. (sic) The tournament this year, as proposed by Coach H.J. Stegeman, of the University of Georgia, at the annual meeting of the S.I.A.A. in Gainesville, Fla., will decide which team in the south is best entitled to the pinnacle place in basketball ranks." - ("Basketball Touranment Plans Given,", by John Mahoney, Atlanta Constitution January 27, 1921.)

As mentioned above, Herman J. Stegeman of the University of Georgia was the person responsible for initially proposing the tournament. Reportedly, he first approached Birmingham Alabama with the idea but the idea was not well received, so he tried again with nearby Atlanta. Stegeman was an enthusiastic supporter of intersectional play and was a driving force behind making the tournament a success. Before his untimely death in 1939, he had written many articles on Southern sports and was a widely regarded expert on the topic. Stegeman graduated from the University of Chicago in 1915 where he played football under the renowned coach Amos Alonzo Stagg. After a stint in the Army during World War I, Stegeman came to Athens where he became the football, basketball and track coach for the Bulldogs.

Joining him was William Alexander, a well-respected coach at Georgia Tech. Alexander graduated from the school in 1912 and took over the head football coaching position in 1920. While he only coached the Georgia Tech basketball team in 1920 and 1922-1924, Alexander still involved himself in the executive committee planning and overseeing the annual basketball tournament through most of its run in Atlanta.

As with Stegeman at Georgia (Stegeman Coliseum), Alexander would later have Tech's basketball stadium named in his honor (Alexander Memorial Coliseum).

|  |

(University of Georgia) | (Georgia Tech) |

|  |

(Athens) | (Atlanta) |

|

Noted John Mahoney in the Constitution:

"The Atlanta Athetic club will sponsor the meet, and Al Doonan, of the A.A.C., will have charge of all the important details of the four days. Mr. Doonan was the guiding hand in the national tournament held in Atlanta and this was most successful. The fact that Mr. Doonan is at the head of the tournament this year insures a successful outcome." - ("Basketball Touranment Plans Given,", by John Mahoney, Atlanta Constitution January 27, 1921.)

Joining Doonan, Stegeman and Alexander on the initial organizing committee in 1921 was Charlie Bernier of Alabama. (although other coaches were named to the organizing committee through the years, this was largely an honorary role as they weren't close enough to Atlanta to accomplish much in the way of organizing the event.)

The organizers were heavily involved in all aspects of the tournament. Not only making arrangements and handling the financials but being present during the games to make sure they ran smoothly and hob-nobbing with the numerous coaches, administrators and alumni who showed up at the event. It was not unusual for Doonan, Stegeman and Alexander to meet the arriving teams at the nearby train station and accompany them to their hotels.

|

When the drawings for the field were pulled from the silver cup trophy, it was Doonan, Stegeman and Alexander who were present, along with any other interested coaches and newspapermen.

|

While basketball was popular among members, the sport took a few years to take hold due to difficulty in finding suitable opposition. Regulars of the club were often pulled together to play against local teams and visitors alike, including notably Yale each December in 1904, 1905 and 1906. In January 1906 an Atlanta-city league was formed, among the A.A.C., the Y.M.C.A. and local colleges. Many of the games were held at the A.A.C. gym along with other venues such as the Peachtree Auditorium, however the interest helped to kick-start interest at Georgia Tech which soon fielded their first team in school history and eventually after a number of years led to them to building their own on-campus gymnasium.

On November 27, 1908 A.A.C. athletic director John Heisman held a meeting and proposed the formation of a permanent standing team to represent the club. Twenty-five year old Al Doonan was elected to be captain. The team consisted of amateur and former collegiate basketball players from around the city. Other stars of the day included G.H. "Tommy" Atkisson and Atlanta Constitution sportswriter Dick Jemison. John Heisman, served as the coach of the team. He was also the basketball, baseball and football coach of Georgia Tech at the time and later became known for the Heisman trophy in football. The A.A.C. team's first game was scheduled against the Birmingham (AL) Athletic Club, followed by games vs. Vanderbilt and other amateur and collegiate opponents throughout the South.

|

This new downtown building had a gymnasium on the third floor and boasted a boxing ring, handball and squash courts, regulation Olympic-sized swimming pool in the basement, lounge, full kitchen with dining room and a roof garden among other amenities. The building also had 63 rooms for members and guests to stay. During the tournament this facility was used to house and feed visiting teams and provided a practice gymnasium as well.

(Note: Some sites on the internet have claimed that the tournament games were held at the Atlanta Athletic Club gymnasium. This is incorrect. The gymnasiums at both the sites prior to and after 1926 were far too small to hold such a tournament (see interior photo) and there's ample evidence that the tournament was indeed held at the City Auditorium every single year.

|

Standing (l to r): Hudson (forward); Spencer (center); "Tommy" Atkisson (center); E. Ramspeck (center); C. Ramspeck (guard) Middle Row: Colquitt (guard); Al Doonan (Captain forward); Davis (manager); John Heisman (coach); Thornton (guard); Post (guard) Front: McGovern (forward); Dick Jemison (forward). Other examples from 1910 and 1912. |

|

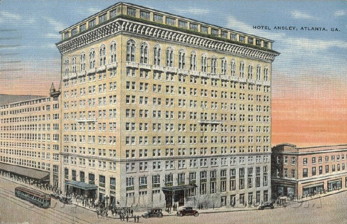

Many other hotels were used by teams over the years. The Piedmont (located on the block between Peachtree, Luckie, Forsyth and Broad streets) was used by conference officials to hold their meetings. The Georgian Terrace (located on Peachtree Street and Ponce De Leon Avenue) and the Henry Grady (built in 1924 and located at the corner of Peachtree Street and Cain Street), among others, are additional hotels used by teams.

At times, the Atlanta Athletic Club and Georgia Tech provided lodging, as well as practice facilities.

Atlanta was also a generous host when it came to entertainment beyond the basketball games. The athletes were treated as minor celebrities around town, and given their stature in height, hard to miss.

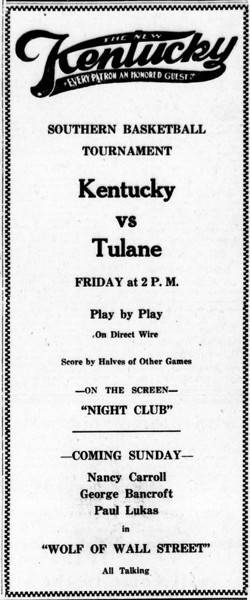

Theater managers were eager to invite squads to attend the latest shows as honored guests. For example, a newspaper article from 1930 mentions the University of Kentucky thanking the managers of the Capitol Theatre, Fox Theatre, and Majestic Theatre for their hospitality during their time in the city when not playing basketball.

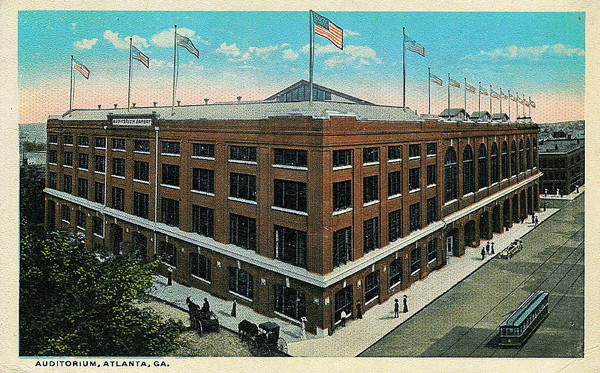

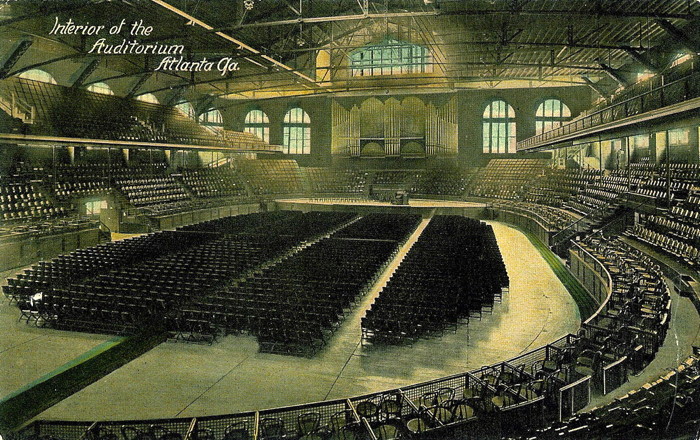

When it came to the S.I.A.A. tournament, there was much to be prepared. Foremost there was no suitable basketball arena large enough to hold a tournament of this scale, and which could allow for the number of spectators that Doonan envisioned.

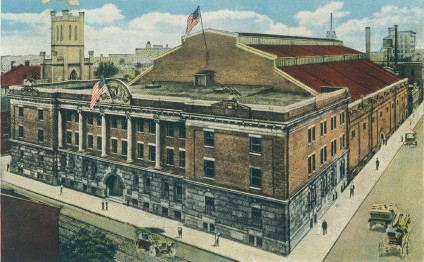

The Atlanta City Auditorium, located at the corner of Gilmer and Courtland Streets in downtown Atlanta, had the physical space and was reserved for the event, although it required some alterations to make it suitable for basketball.

|

|

Sidenote: Today, what remains of the building is known as Dahlberg Hall and is part of Georgia State University. The following article (pdf) commemorates 100 years of the building (at the time called Alumni Hall) and provides some background and history. (Article courtesy of Jeremy Craig, Georgia State University).

In addition, music historian Wayne Daniel put together a Youtube video discussing the history of the building and what the area where it stood looks like today. During the demolition of the auditorium, Daniel took some interesting photographs (Link 1, Link 2). (Photos courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library and Wayne Daniel).

|

Construction of this building began in 1907 and was dedicated in 1909 by then-President William Howard Taft. The building was used for various concerts, theatre productions and other events, including notably the "Gone with the Wind" ball. It also served as the city's Armory. The entrance to the building was on Courtland Street facing Hurt Park, while the arena itself sat behind the Armory with its distinctive arched windows easily seen along Gilmer Street.

The City Auditorium was part of a WPA renovation in the mid-1930's, although not much later afterwards, the front section burned in 1940 (the Auditorium itself was saved by a fire wall). Since that time the building has undergone renovations and reconstruction, including an overhaul of the facade from brick to marble.

In its later life, the building housed the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and was used to stage numerous concerts by top acts in the 1960's and 1970's, along with numerous wrestling events. In 1979 the building was sold to Georgia State University, which demolished the Auditorium section in 1981. (see sidenote for photos).

In order to make the facility suitable for basketball, $3,000 was invested before the first tournament to build a temporary elevated court that was installed at stage height. Construction of the floor proved to be the single largest expense for the tournament organizers each year.

On an annual basis, bids went out prior to the tournament and a new court was built from scratch. Typically the contractor began construction of the court immediately after the previous event was completed. Working through the night, it typically took a full day and a half to complete the task, with additional time allotted to paint lines and allow them to dry.

Although supports intended for use in bridge construction were utilized, the quality of the floor was not always sufficient. Players often complained of bounciness. During at least two seasons, the players tore 'divots' in the floor, with one in 1929 reportedly six-inches long and another in 1931 consisting of three planks. Carpenters had to be summoned out of the crowd to fix the damage before play could resume.

To make the venue more amenable to the crowds, scoreboards were provided and game programs were made available, with rosters and numbers so that spectators could identify the players. Oftentimes the arena was decorated with large bows and streamers to provide a festive atmosphere.

During this era, not all basketball courts were regulation size and many teams were not used to such a vast expanse when they did play on one. That (along with the fact the court was raised above ground level and the sheer size of the Auditorium) made playing in the tournament a unique and memorable experience for many of the players.

Because of the possibility of inequity between teams who were familiar with the court versus those who weren't, the court inside the City Auditorium was generally off-limits to teams for practicing, except for a few minutes allotted to them before each game (generally during halftime of the previous game). Instead, the teams were offered practice time at Georgia Tech, along with the gymnasium at the Atlanta Athletic Club.

|

Because the games were held every hour in a steady stream, there was no practical way to seat crowds before every game. Instead, a day pass was made available for purchase for $1.00, $1.50 for boxed seating. No return passes were provided, however, so anyone leaving the venue was required to purchase another ticket. In the early rounds, typically there was an hour break for dinner, so anyone who didn't want to pay the reentry fee needed to bring their own food. A hot dog stand was set up inside the auditorium for those needing a snack.

|

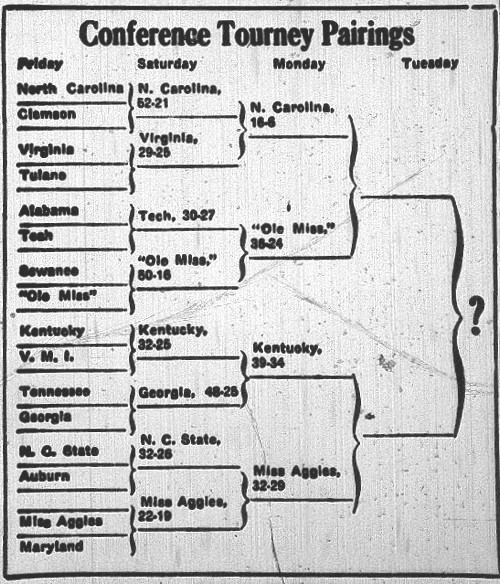

Usually the top four seeds were determined by the committee and seeded in opposite brackets in order to avoid matching them up in early rounds. The remaining teams were subjected to having their names placed into the championship cup and being placed in brackets via a blind draw.

The brackets were set up as single elimination, with the exception of third-place consolation games which were held in 1922 and 1923. Due to the irregularities in number of entrants, many early tournaments were required to hold preliminary rounds or utilize byes for selected teams. In cases where the Auditorium floor was not ready in time, the Atlanta Athletic Club was used to host the preliminary games.

Subsequent Southern Conference tournaments in Atlanta saw the field narrowed, in order to reduce the number of days away from school, and to improve the quality of play. Eventually the organizers arrived at a working number of 16 participating teams, which was considered optimal.

Typically the tournament began on the last Friday of the month of February. The quarter-finals were held on Saturday afternoon and evening while the semi-finals and finals were held Monday and Tuesday evenings respectively. No games were ever held on Sunday.

Games were typically scheduled every hour on the hour, meaning that a full 40-minute game was expected to be completed within a hours time. To help accomplish this, teams from the upcoming match were expected to warm-up during the halftime of the preceding contest.

|

The layout of the floor was such that the media was given a sideline from which to observe the play up close, albeit because of the raised floor the newspapermen were always craning their necks to look upwards.

Morgan Blake was a long-time mainstay of Atlanta sportswriters. Originally a graduate of Vanderbilt, he left jobs in Nashville and became the sports editor of the Atlanta Journal in 1916.

Ed Danforth, a 1914 graduate of the University of Kentucky, moved to Atlanta in 1919 to take a position with the Atlanta Georgian where he became editor. Danforth later joined the Atlanta Constitution and became a prominent sportswriter in Atlanta until he retired in 1957.

Cliff Wheatley was the young sports editor of the Atlanta Constitution who is credited with popularizing the nickname "Bulldogs" as the mascot of the University of Georgia athletic teams. Wheatley later died at a young age in 1927, due to the after-effects of pulmonary gas injuries he suffered during World War I.

| Atlanta Georgian | ||

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| Atlanta Journal |  |  |  |

(Edwin Camp) |

| Atlanta Constitution | ||

|  |  |

(JPS Note: One notable member of the above group was Ralph McGill of the Constitution. McGill went on to become the general editor of the paper and later a syndicated columnist with a national audience. McGill was known to be one of the few editors of a white southern newspaper to take a public stand against segregation during the 1950's and 1960's.)

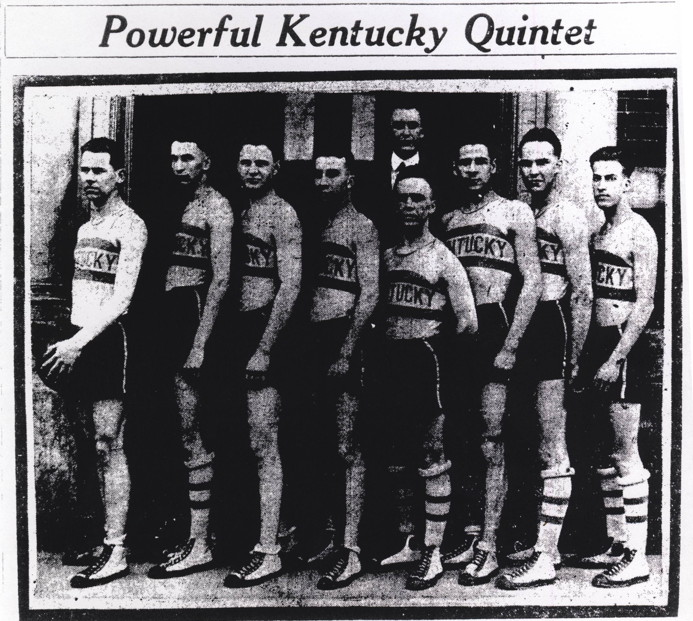

The first official tournament was held in late February 1921. The Kentucky Wildcats defeated the pre-tournament favorite, the Georgia Bulldogs, on a last-minute free throw by Kentucky forward William King.

|

Prior to the championship game, long-time foes Georgia and Georgia Tech met each other on the Auditorium floor in the semi-finals, with Georgia taking the victory, 26 to 21. The two schools had not met each other in athletic competition since 1919 and at the time were forbidden from playing each other under normal circumstances. The game was met with great anticipation and the crowd was a sell-out.

Noted Charley Bernier, coach of Alabama who Georgia Tech had dispatched earlier in the tournament:

"I'm tickled to death that Tech beat us Saturday night and made this night possible," he said. "We would have been put out of the running anyhow, and tonight has been one that will be long remembered in southern collegiate athletics. Unquestionably this is the greatest crowd that ever saw a basketball game. I have never seen anything that remotely approached it in the east. The splendid way in which the affair has been conducted will wake the other sections up to the fact that we now to do big thing in an athletic way in the south." - ("Immense Crowd Sees Close Game Won by Georgia,", by Fuzzy Woodruff, Atlanta Constitution March 1, 1921.)

Tech and Georgia weren't the only bitter rivals who were forced together by participation in the Southern tournament. The event helped to bridge a number of other divides which otherwise would have remained for many more years.

The following season in 1922, the University of Kentucky and nearby Georgetown (KY) College met to decide the Kentucky state championship on the Atlanta floor. The two teams had split the season series, each winning on the other's home court with an identical score, 26-17. Georgetown coach Paul Rhoton mentioned in a letter that the only reason the Tigers entered the tournament in the first place was to gain an opportunity against UK. As it turned out the two were slated to meet each other in the first round. The two opponents shared a Pullman car on the trip down. Kentucky won the rubber match, although neither team appeared to be at ease on the large floor in the City Auditorium.

That same year Georgia and Georgia Tech met for the second time, again without incident. Noted Atlanta Georgian columnist, Ed Danforth: "Twice the teams have met and not a player has taken a poke at another; not a student has shied a brick at another; twice they have convinced everybody except - well, whoever it is who severs athletics relations - that teams from the two schools can meet without mayhem. Do they have to be convinced three times?"

In 1924 the pairing promised that three ancient rivals who no longer played each other could face each other in the second round. This included Auburn-Alabama, Georgia-Georgia Tech and Washington & Lee - Virginia Military.

Washington & Lee telegraphed to the committee prior to the 1924 tournament "please see in your pairings that under no circumstances will it be possible for Washington & Lee and V.M.I. to meet in the early rounds." The committee wisely decided to ignore these special requests and instead pulled names blindly out of the championship trophy. As it turned out these two neighbors were paired to meet each other in the second round, but each were beaten convincingly in the first round, making the objection moot.

The Alabama-Auburn matchup did occur in the quarterfinals, however, and the two schools met for the first time in 17 years. There was so much interest in the game that details of the game were sent by telephone to the Alabama gymnasium where a large crowd, paying $0.10 apiece, gathered to hear the results.

S.I.A.A. to Southern Conference

|

These schools were: Alabama, Auburn, Clemson, Georgia, Georgia Tech, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi A.&M., North Carolina, North Carolina State, Tennessee, Virginia, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, and Washington & Lee.

The intention was to create a workable group of schools from which to establish regular schedules, and to establish a common set of rules which all schools were expected to abide by.

As reported in the Atlanta Constitution: "The basis of the new association is a sweeping departure from all athletic standards that ever prevailed in the South; the new constitution is hailed by the makers as a remarkable forward step for purification of Southern athletics."

As part of the formation of the conference, rules were enacted for the schools to abide by. One rule stipulated that players would have three years of eligibility. This ushered in an era where freshmen were no longer eligible to play varsity, and in turn freshmen teams were formed.

Another rule adopted by the group was the anti-migratory rule, which prevented an athlete from leaving one college to attend another and playing on the athletic team there.

The new conference was to become official on January 1, 1922. Its first president was S.V. Sanford of the University of Georgia, while N.W. Dougherty, University of Tennessee, was elected secretary and treasurer.

While fourteen founding members were announced, it was made known that the preferred number of schools would be 16, with the two additional spots being filled by applicants. As it turned out, six schools joined within the year: Tulane, Florida, Louisiana State, Mississippi, South Carolina and Vanderbilt. Later on Virginia Military joined the conference in 1925 and Duke University joined in 1929.

|

The first few years, the tournament welcomed applicants from both the newly formed Southern Conference, along with what remained of the S.I.A.A. The winner of the tournament could legitimately proclaim themselves to be "Champions of the South." This arrangement lasted until the 1924 season when the S.I.A.A. moved to their own conference tournament, held in a newly built auditorium in Macon, GA. It was also this year that the Southern Conference dropped the third-place consolation game.

|

Yates was originally from Pennsylvania and played briefly in professional baseball. He had become affiliated with the Atlanta Athletic Club by the time the tournament was created. He was highly regarded in the South as a referee. Noted Cliff Wheatley of the Atlanta Constitution when Yates was named as an official for the 1922 tournament:

"Dave Yates will need no introduction to the basketball fans within range of these paragraphs. The truth of the matter is that Yates has done more to educate court followers than perhaps any other man in the south today.

"When he came upon the scene, Dixie's basketball was a mixture between football and manslaughter, the latter being the ingredient used mostly by the basketeers. There was a crying need for reform and Dave has certainly done his share in remedying the evil.

"He is thoroughly versed in every angle of basketball. We doubt if there is any many in the country possessing more actual knowledge of the pastime." - ("Yates, Sutton, Journet (sic) Listed," by Cliff Wheatley, Atlanta Constitution, February 5, 1922.)

|

Walker Reynolds "Tick" Tichenor proved to be a mainstay of the tournament, in his role as the official timer. Tichenor had been a famous collegiate football player in the 1890's, who had played for both Auburn and (while he attended law school) Georgia. Noted Ralph McGill in an article about old-time football in the 1890's "One of the finest things the basketball tournament has done is to bring Reynolds (Tick) Tichenor out of retirement and into the star-chamber session at the Atlanta Athletic Club." ("Break of the Day," by Ralph McGill, Atlanta Constitution, March 1, 1932.)

In an earlier article, Tichenor relates a story from the first tournament when he chose to use a pistol to end the game.

There was a John Law in the place and he came galloping over and seized Tick Tichnor, who still held the smoking rod in one hand, "I arrest you," he said, "for shooting in a public place." The copper was a large one and he held the rather slight Tick Tichnor in a firm grasp. What made it worse was that Mr. H.J. Stegeman, the Georgia coach, felt that he had been severely wounded by the gun going off with his team one point behind. So he charged that Mr. Tichenor had shot him in the leg. It was some time before Mr. Al Doonan and Coach W.A. Alexander could persuade the copper that it was alright to have a man flourish his artillery and let it boom all over the place. - ("Tick Tichnor Pioneer Tourney Pistol Popper," by Ralph McGill, Atlanta Constitution, February 22, 1932.) (JPS Note: The game in question (between Kentucky and Georgia) was tied when the gun went off and Bill King at the foul line ready to shoot a free throw. The sound alarmed King but he went to hit the shot giving Kentucky the victory.) |

Each year a select number of officials were hired to work the games. Typically three officials called the entire tournament and they alternated roles during the day. So for example one acted as umpire, while another was the referee and the third worked as the official scorer. Given that the games were often held back-to-back-to-back-to-back and the early rounds consisted of two sessions, this would make for an exhausting day of work!

Although there were similarities and overlap, the roles of the referee and umpire were distinct. According to the 1922-23 Spalding's Official Basketball Guide, the role of the referee included:

"The Referee shall put the ball in play; shall decide when the ball is in play, when the ball is dead, to whom it belongs and when a goal has been made. He shall call violations and fouls, shall administer all penalties, shall recognize substitutes, and shall order "time out" when necessary. He shall announce each goal as made, indicating with his fingers the point value of the goal. He shall also publicly announce the score at the end of each half. This final announcement terminates his official connection with that game."

In contrast, the duties of the Umpire include:

"The Umpire shall call violations and Duties of fouls committed by any player, but he shall pay particular attention to the players in the back field away from the ball. The Referee shall request the Umpire to assist in out-of-bounds decisions and to co-operate in enforcing the rule against coaching."

|

Another successful Eastern Coach, Harry Fisher of Army, was coming off an undefeated season at West Point and served as the third official during the 1923 tournament. Fisher was later inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame for his contributions to the sport.

| Year | Officials |

|---|---|

| 1921 | Stanley Sutton & Dave Yates |

| 1922 | Stanley Sutton, Dave Yates & Lon Jourdet |

| 1923 | Stanley Sutton, Dave Yates & Harry Fisher |

| 1924 | Stanley Sutton, Dave Yates & Tom Thorp |

| 1925 | Stanley Sutton, Dave Yates & Lou Ervin |

| 1926 | Stanley Sutton, Paul Menton & Ed Thorp |

| 1927 | Stanley Sutton & Paul Menton |

| 1928 | Stanley Sutton, Paul Menton & Tom Thorp |

| 1929 | Stanley Sutton, Paul Menton & Tom Thorp |

| 1930 | Stanley Sutton, George Wood & Bernard Eberts |

| 1931 | Stanley Sutton, J. Olney "Bowser" Chest & George Wood |

| 1932 | Stanley Sutton, J. Olney "Bowser" Chest & Frank Lane |

| 1933 | J. Olney "Bowser" Chest & George Wood |

| 1934 | J. Olney "Bowser" Chest & Bunn Hackney |

|

Thorp, who also was a sportswriter penned an article for the Atlanta Georgian during the 1924 Southern Conference tournament where he praised the athletes and coaches. Wrote Thorp:

"This, too, in the face of the fact that I have never seen so many big huskies playing in a single tournament. Because of this the splendid spirit displayed is one of the big, outstanding features of the series. The Southern Conference is to be heartily congratulated upon the fact that its coaches teach the grade of game that their charges display under fire. A true test of an athlete's sportsmanship is only had when the latter in the heart of a hot scrimmage. If he has had the right grade of coaching he stands up under the test. If his mentor tolerates unsportsmanlike conduct, the players soon resort to unwholesome tactics.

"For the very reason it is my belief that too much credit cannot be given to the fine sportsmen who are engaged as coach in the Southern Conference. Their fine, clean temperaments are reflected in the sportsmanlike way their pupils conduct themselves on the court." - ("Thorp Praises Teams and Crowds Here," by Tom Thorp, Atlanta Georgian, March 3, 1924.)

The third official in 1925 was Lou Ervin, the manager of the Birmingham (AL) Athletic Club. Ervin would also officiate in the S.I.A.A. tournaments in Macon, Ga.

After the 1925 tournament, Dave Yates left Atlanta to take a position with the American Red Cross in Washington D.C. (previously Yates was the southern director for life-saving and first aid with the Red Cross in Atlanta.) When Yates returned to Atlanta for a visit in 1926, The Constitution hailed him by saying "It was Dave Yates who revolutionized basketball in the south when he came into this part of the country to act as referee in the inter-collegiate basketball tournaments." (Atlanta Constitution, "Dave Yates Visits Atlanta", September 1, 1926).

|

Menton began refereeing the Southern Conference tournament in 1926 and would continue to return to Atlanta to referee the tournament until 1929.

Alongside Menton in 1926 was Tom Thorp's brother, Ed Thorp, who took a turn officiating the Southern Conference tournament as a last minute replacement when Tom had been involved in an automobile accident and was not able to officiate. Ed had been the head basketball coach at New York University between 1919-1923. (Thorp died at a young age in 1934 and was memorialized with a large traveling trophy in his name, which the National Football League used to award to its champion between 1934 until 1969, before they adopted the Lombardi trophy.)

Tom Thorp was also scheduled to officiate the 1927 tournament but once again had to bow out, leaving Menton and Sutton to officiate the entire affair by themselves (the first time this had been done since the initial 1921 tournament). Tom Thorp later returned to officiate in 1928 and 1929.

Beginning at the 1931 tournament, J. Olney "Bowser" Chest joined the officiating crew. Chest, a native of Nashville, TN and alumnus of Cumberland (KY) College, went on to become a mainstay of Southern basketball as he officiated the 1931 and 1932 tournaments, and then continued to officiate every Southeastern Conference tournament until he retired in 1952).

|

|

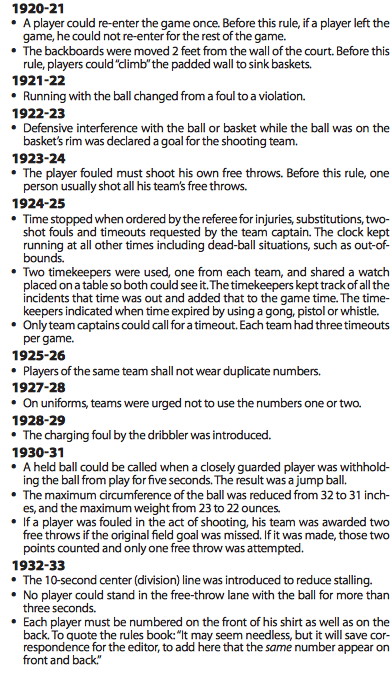

The first year of the S.I.A.A. tournament, the rules had been amended to allow a player who had come out of the game to substitute back in, but only once. With only ten players allowed to travel to Atlanta, this was a big help in terms of managing players through the game.

Not mentioned in the list to the right is the conference rule which was enacted as part of the formation of the Southern Conference which made freshmen ineligible to play varsity. It's not clear if this went into effect as part of the 1921-22 season or more likely the 1922-23 season.

Another major change was for the 1923-24 season, for the first time each player who was fouled was required to shoot their own free throws. Prior to this time, a shooter (of the men who were playing at the time) was designated by each team as the person to take all the free throws.

Perhaps an overlooked rule which helps to explain the pace of the tournament is mentioned that in 1924-25 "Time stopped when ordered by the referee for injuries, substitutions, two-shot fouls and timeouts requested by the team captain. The clock kept running at all other times including dead-ball situations, such as out-of-bounds."

This information is interesting because it helps explain how these teams were able to complete a 40-minute basketball game within an hour of elapsed time. It was because the clock was running much of the time, whereas in today's modern game the clock is stopped in all dead-ball situations.

|

Another perhaps surprising rule was from 1922-23 where it stipulates that a goal declared for the shooting team if the ball is interfered with on the rim. This suggests that there was play above the rim during this era, another assumption that many people of today assume didn't occur at the time.

One significant change was the development of the basketball itself. In 1929 basketballs were redesigned to hide the laces which held the ball together, and thus improving the ability to dribble. Before the 1930-31 season, the size and weight of the basketball was reduced (from 32 to 31 inches circumference and 23 to 22 ounces). This likely helped to improve field goal percentage. Note that the circumference was later reduced yet again and stabilized at 30 inches by the 1938-39 season. These changes were in concert with a marked increase in points scored per game. Current NCAA basketball's maximum circumference is 30 inches while NBA basketball's are between 29.5 and 29.875 inches in circumference.

There were also rules related to uniform numbers, and inclusion of a 10-second center line to reduce stalling over the entire length of the court.

One improvement in terms of uniforms was the large-scale adoption of Converse basketball shoes. The "All-Star" was first designed in 1917 by the Converse Rubber Shoe Company and later the design was improved upon by one of their salesmen, former basketball player "Chuck" Taylor. in 1923. This went on to become the most popular shoe in history.

|

|

There were also physical improvements to the game. Internal lighting and amplifiers were utilized to improve the game experience of spectators and to allow them to hear the public address announcer.

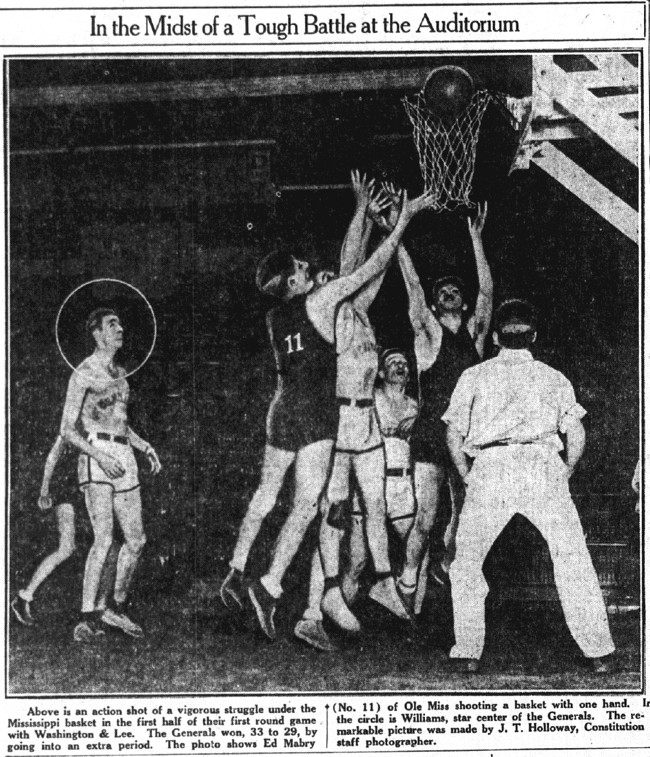

One area which can be seen as the tournament progressed was the use of interior action shots. Action photographs of daytime outdoor football games were relatively commonplace since the early part of the century, but action photographs of basketball games were all but non-existent.

That began to change in the mid-1920's when portable cameras which could be used in relatively low light conditions and able to capture fast-action as well; the exact conditions which made the game of basketball difficult to capture on film.

One popular brand of camera was from the German company Leica, which set up sales offices in metropolitan cities around the United States to export cameras. These cameras were relatively expensive, but were put to great use by news organizations among others. This paved the way for the inclusion of early action photographs from basketball games, including ones of the Atlanta tournament (and some of which are included on this site). It was not until the late 1930's that action photographs of basketball games became relatively commonplace.

|  |

|

The tournament proved to be a great stage for stars throughout the South to shine and gain fame. From the very first tournament where Kentucky's Basil Hayden stole the spotlight, the list of stars is long.

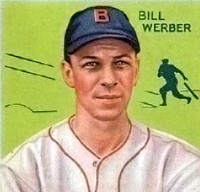

This includes: Cartwright Carmichael and Jack Cobb, stars of the early North Carolina Tar Heel teams; UT-Chattanooga's high scoring player-coach Bill Redd; Oglethorpe's monster center "Tiny" Roberts; the Tulane Green Wave's Ellis Henican; Alabama's Leonard "Slim" Carter; Georgia Tech's "Babe" Roane, Doug Wycoff and "Tiny" Hearn; Georgia's Charlie Wiehrs, Nolen Richardson and Bill Strickland; Vanderbilt's Jim Stuart; Ole Miss' Cary Phillips; Auburn's "Jelly" Akin; Duke's Joe Croson, Bill Werber and Harry Councilor; Alabama's James "Lindy" Hood; N.C State's Morris Johnson and Frank Goodwin; Maryland's Louis "Boze" Berger; Kentucky's Paul McBrayer, Forest Sale and John "Frenchy" DeMoisey; Tennessee's Maurice Corbitt; Florida's Mel Emmelhainz; Louisiana State's Jack Torrance and Malcolm "Sparky" Wade among many others.

A few of these players were recognized as All-Americans, although many more were overlooked, as Southern basketball was not fully recognized in comparison to the East Coast and Midwest at the time. When these players did receive recognition, it was often for what they accomplished during the tournament in Atlanta.

At the time there was not much in the way of professional opportunities in basketball, especially in the South once the players left college. A number of alumni of the Atlanta tournament did pursue professional opportunties in other sports. For example Fred "Tiny" Roberts of Georgia Tech became a boxer. A significant avenue was through Major League Baseball.

|  |  |

(Tulane) | (Duke) | (Maryland) |

| Three alumni of the Atlanta tournament who went on to pursue careers in Major League Baseball | ||

|---|---|---|

In addition, there were many brother combinations who made their mark in the Atlanta tournament. This included Angus "Monk" and Sam McDonald of North Carolina, Roger and Terry Snowday of Centre College, Cartwright and Billy Carmichael of North Carolina, Joseph and C. Ellis Henican of Tulane, twins Cary and Ary Phillips of Ole Miss, twins Ebb and Fob James of Auburn, Rufus and Bunn Hackney of North Carolina, Louis and Lawrence McGinnis of Kentucky, Ed and Zeke Kimbrough of Alabama, among others.

Along with great players, the tournament was also a showcase for great coaches. (Although it should be noted that the coach was handicapped by rules which prevented him from talking to his team on the floor. It's not clear how much instruction was actually allowed during this era. It wasn't until 1948-49 that coaches were allowed to speak to their players during a time-out.)

Many of the teams even during the 1920's went without a coach. The University of North Carolina had no official coach in 1922 or 1923, but that didn't prevent them from winning the tournament championship in 1922. Bill Redd of Tennessee-Chattanooga not only was the star player for the Moccasins, he also served as player-coach of the team, and they made it to the quarterfinals in 1922 and finals in 1923.

|

Another famous local coach was Josh Cody, who at the time of the first tournament was coaching Mercer, after he had graduated from Vanderbilt University in 1920 where he starred as a football All-American. Cody later returned to Vanderbilt, where he led the Commodores to the Southern Conference tournament title in 1927, even though he had earlier agreed to become the head football and basketball coach at Clemson. Cody coached at Clemson from 1927 to 1931, but subsequently returned to Vanderbilt. Years later he moved to Florida and then Temple where he became a legend at that school. In all, Cody represented three different schools in the Atlanta tournament.

|

Another player who saw action in the tournament, only to return as a successful coach was Washington & Lee's Eddie Cameron. Cameron played in the 1924 tournament as captain of the Generals. The following season the Generals returned with Cameron as the head coach. Cameron later took an assistant football coaching position in 1926 at Duke University. He became head coach of the Duke basketball team starting in the 1927-28 season, and brought the Blue Devils to their first Southern Conference tournament in 1929. This was after Duke joined the conference in 1928.

Other notable coaches in the tournament included Hank Crisp (Alabama), W.H. Britton (Tennessee), H. Burton Shipley (Maryland) and Adolph Rupp (Kentucky), among many others.

|

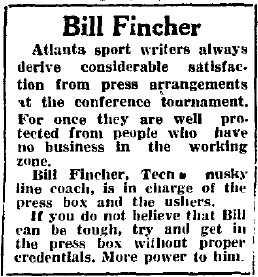

Seated (l to r): Harry Robertson (Oglethorpe), Bill White (Georgia), Harry Mehre (Georgia), Frank Thomas (Georgia), M.B. Bennett (Sewanee), Gus Tebell (North Carolina State), James Ashemore (North Carolina), Ed Cameron (Duke), Roy Mundorf (Georgia Tech), H.W. Robinson (Georgia Tech) Second Row: William Alexander (Georgia Tech), Francis King (representative of O'Shea knitting mills), Varnahan (Syracuse), W.H. Hutson (Auburn), Chick Meehan (New York University), Bill Rafferty (North Carolina), Georgia Griffin (McCallie), B.W. Bierman (Tulane), Hank Crisp (Alabama), Harry Rabenhorst (L.S.U.), Josh Cody (Clemson), Bill Fincher (Georgia Tech) Back Row: Kid Clay (Georgia Tech), C.C. Collins (Tulane), Claude Simons (Tulane), Homer Hazel (Mississippi), Dick Smith (Tulane), G.W. Bohler (Auburn), Robert Neyland (Tennessee), W.B. Britton (Tennessee) (Note for a larger version of this photo, please see this link. Photo from Atlanta Constitution (March 5, 1929)) |

The tournament provided a perfect opportunity for officials of all the major schools to meet, often in an informal setting. The photograph above gives a flavor for the sheer number of top coaches and administrators who were attracted to and present during these events. Many of the people were considered legends at their respective schools.

The tournament also attracted local celebrities, alumni, coaches from outside the region and coaches of other sports. Noted Ed Danforth in a 1930 column about Southern Conference football coaches:

Harry Mehre and Frank Thomas came over from Athens last night, having called a halt in their spring football practice for the occasion. Other football specialists who secretly do not care a lot about basketball will be on hand this morning. "Why do you come down every year for this show?" I asked Coach Gamage yesterday. "Oh, to talk football," replied Mr. Gamage pleasantly. The gridiron future of the Southern conference football will be all settled before the clock has turned again. If you want to glean all the dope on next fall's activities come to the tournament and keep both ears open. - ("Mawnin'!," by Ed Danforth, Atlanta Constitution, February 28, 1930.) |

Noted Morgan Blake in 1933 about football coaches: "Football coaches always gather in large numbers at these basket ball tourneys. They enjoy them too, because they have no responsibilities in regard to the basket ball teams, and they experience some grim satisfaction in observing the suffering of the coaches of the quintets. And then the grid mentors delight in gassing around with one another and the fans and sports writers." - ("Sportanic Eruptions: Vale Tech And Georgia!," by Morgan Blake Atlanta Journal, February 25, 1933.)

|

One topic of conversation was the very placement of the tournament in Atlanta. An article in the Atlanta Constitution noted that the University of Kentucky had been looking to host the tournament, but were stymied by the lack of a municipal auditorium in the city of Lexington in which to provide a neutral court. And while there was grumbling among the coaches about Atlanta's stranglehold on the event, no serious bid was ever presented to move the tournament to another city. So Atlanta 'won' by default. Wrote Danforth:

"The Atlanta Athletic Club has no desire to hold a monopoly on the event. It involves a lot of work, scant glory, and very few thanks. Few, if any, efforts have been made to 'land' the assignment each year.

"Atlanta has been awarded a monopoly on the event by default, you might say. It is no small undertaking to assume responsibility for $10,000 expense and promote the affair so that the deficit prorated among the competitors, will be negligible. Yet this has been the case ever since Atlanta began staging the tournaments. Now and then there has been a surplus which was passed on to the Conference for use the next year.

. . .

"No serious objections would be offered if some other locality decided to bid for the tournament next year. Yet when it comes down to making a serious bid, the silence is deafening. The grumbling ceases. The Atlanta show is not really so bad after all." - ("No Foreign Bid Heard for Next Tournament," by Ed Danforth Atlanta Constitution, March 6, 1930.)

Another hot topic of conversation, which came up time and again, was the possibility of a split of the Southern Conference. Even though the Conference was smaller than the S.I.A.A. from which it came, the size was still too large and the geographic spread made it unwieldy for teams to travel to face schools in other regions during the regular season.

In 1931 Ralph McGill wrote an article discussing a fictional character by the name of "J. Conference Splitt", as a way to broach the topic. Wrote McGill:

"Sometimes I think maybe we ought to let him [J. Conference Splitt] come into the meeting," he [Kentucky president and secretary of the conference Dr. W.D. Funkhouser] said. "The newspaper men like him so well. He is a great friend of theirs. In fact, if it were not for Mr. Splitt, I fear that the newspaper men might find the Southern conference meetings very dull indeed. As it is they come to our meetings, ask innumerable questions and occupy our minds.

"It is slightly embarrassing to have the newspaper men keep accepting the word of this fellow Splitt and refusing to take the word of the estimable gentlemen in our executive committee. They insist that J.C. Splitt has no standing but somehow he managed to make the newspaper men think different." - ("J. Conference Splitt Whispers at Tournament," by Ralph McGill Atlanta Constitution, February 28, 1931.)

By 1932, the conference tournament appeared to be going strong, despite the ill effects from the economy due to the onset of the Great Depression. Noted Atlanta Journal columnist Edwin Camp (aka Ole Timer):

"The annual basket ball tournaments have become a great event on Atlanta's sport calendar. The scene Friday night, with more than five thousand wildly excited men and women in the audience, and courageous young men battling at top speed for the glory of their college on the floor, is indeed thrilling. These tournaments have become a fixture in Atlanta now. And should always be continued. There is no basket ball feature in the nation that can compare with it." - ("Georgia's Great Team Play," by Ole Timer Atlanta Journal, March 1, 1932.)

|

During the annual Southern Conference meeting in December 1932, held in Knoxville TN, it was determined that thirteen of the then twenty-three Southern Conference schools were leaving to form the Southeastern Conference (S.E.C.). This was announced by Dr. John J. Tigert, president of the University of Florida, during the organization's annual banquet. The thirteen teams were: Alabama, Auburn, Florida, Georgia, Georgia Tech, Kentucky, Louisiana State, Mississippi, Mississippi State, Sewanee, Tennessee, Tulane and Vanderbilt.

Noted Tigert in explaining the reason for the split: "Since, in our judgement, the time has arrived for a more compact organization for the administration of athletics, it seems wise for a division of the Southern Conference to be made solely on geographical lines." - ("Tech and Georgia Among ...," Atlanta Journal, December 10, 1932.)

The formation of the new conference was immediate. Some changes which were adopted by the new group included: reaffirming the intention to hold the annual basketball tournament in Atlanta, moving the date of the annual meeting to coincide with the basketball tournament (i.e. the last Friday and Saturday of February going into early March), allowing schools to broadcast games over the radio (something which previously was banned), along with other minor decisions.

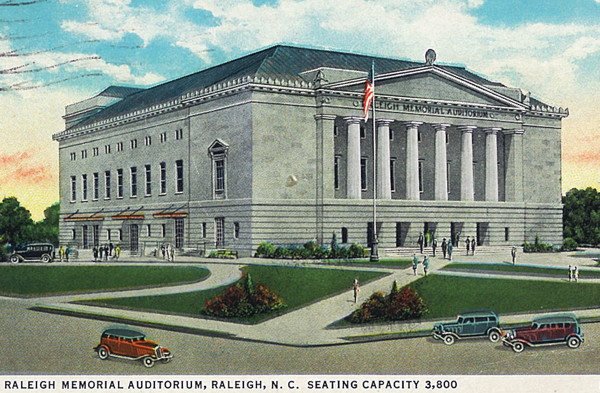

The remaining 10 members of the Southern Conference (Virginia, Clemson, North Carolina, N.C. State, Washington & Lee, Virginia Tech, South Carolina, Maryland, Virginia Military and Duke) shifted their focus eastward and northward along the Atlantic coast, and began playing their conference tournament in the newly built Memorial Auditorium in Raleigh (the Memorial Auditorium was built in 1932 after Raleigh's original City Auditorium burned down in 1930.)

|

Later in 1936 seven smaller schools were added to the Southern conference (Wake Forest, George Washington, Richmond, William & Mary, The Citadel, Davidson and Furman.) This 16-team conference continued on as the Southern Conference, adding West Virginia in 1950. They also continued the tradition of the post-season tournament that was started in Atlanta.

In 1953, most of the original larger schools broke apart from the Southern Conference to form the Atlantic Coast Conference (A.C.C.), although from the group of schools which joined in 1936, they took only Wake Forest with them. The A.C.C. also adopted the old and popular tradition of holding a post-season conference tournament, and in fact that tradition has continued to this day. Meanwhile the remaining members of the Southern Conference also continued their tournament tradition. Despite the member schools changing over the years, the tradition has remained and the Southern Conference tournament remains the oldest and longest-running tournament in collegiate history.

(JPS Note: In fact, between the S.I.A.A. tournament which branched off to Macon, Ga. in 1924, the Southern Conference which moved to Raleigh, N.C. in 1933 (and later spawned the A.C.C. tournament) to go along with the Southeastern Conference tournament, the Atlanta tournament as originally envisioned by Al Doonan in the early 1920's led to a strong legacy of post-season basketball tournaments throughout the South. No other region of the country had nearly as many such tournaments until the 1970's and 80's, and certainly none had been so long-standing and rich in history and tradition. Al Doonan himself did not live to see the fruits of his work, however, as he died in 1936 at the age of 52.)

As far as the Southeastern Conference, although the newly formed conference announced their intention to retain the annual post-season basketball tournament in Atlanta, it only lasted in the city two more seasons (1932-33 and 1933-34).

Prior to the 1935 tournament, it was announced that all conference tournaments (including the basketball tournament) would be cancelled. The primary reason cited was due to the expenses associated with holding the event in the midst of the Great Depression. Even with the announcement, some were already clamoring to have the event reinstated.

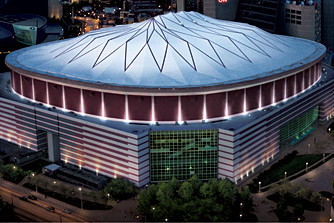

The S.E.C. did return to playing the tournament in 1936, but it was in a new location, on campus at the University of Tennessee's gymnasium in Knoxville. As part of the new arrangement, the number of participants was reduced in order to reduce the number of games, and in turn the number of days required along with reduced expenses. The SEC Tournament location later moved to Louisville, Kentucky where the tournament was held in the Jefferson County Armory (now known as Louisville Gardens) until 1952.

|

The Southeastern Conference tournament was suspended from 1953 until it was reinstated in 1979. Since that time the venue has changed every year, although Atlanta has hosted the tournament quite regularly, including 2014.

With the recent announcement of the intention to make Nashville the 'permanent' home for the SEC Tournament in coming years, it may be a long time before the tournament returns to its origins in Atlanta, Georgia.

|

![]()

|

| Continue to Overview |

![]()

Please send all additions/corrections to