![]()

Misconception

|

The players and teams back then were working hard to become national champions, just as today's athletes are. Just because there was no NCAA Tournament at the time does not make their achievements as National Champions less significant.

![]()

The Facts

| An Elusive Idea | Setting the Stage | Enter the Helms Foundation |

National Champions - An Elusive Idea

Basketball in the early twentieth century was a relatively minor sport and extremely fragmented regionally throughout the country. Largely due to the influence of particular coaches at the collegiate and high school levels, there were hotbeds of interest in the sports, such as on the East coast, the Midwest and few places out West but they were generally isolated from others. Because of this fragmentation and isolation from other regions, distinct styles of play and interpretation of the rules took root.

Most schools and universities played schedules against small colleges and universities in their respective regions along with local teams, including YMCA and other non-scholastic teams. There were a handful of schools which made tours outside of their natural regions, however this practice was sporadic and was more the exception than the norm for that time.

As far as the concept of national champions, there was from time to time the notion that a particular team may be the best in the country (and as will be described later, this idea sporadically was tested), but it typically took the form of a regional boast rather than a realistic or attainable goal, since there was no defined path to achieve it, and no one was in a position to authoritatively determine or proclaim who was the best.

Not only was this concept not practical due to a general lack of intersectional games, but there were barriers in terms of style of play and interpretation of rules.

|

Continued Camp:

"Basketball has come to a very high point of public interest and loyal enthusiasm is intense, but for all this it is decidedly confined as compared with many other sports. A local flavor seems to pervade it; that is, everyone knows all the teams in his own league and something about a few of those that are prominent in other sections, but as for any idea of countrywide comparison, in spite of some interest seems to be entirely lacking.

The reason for this is that while the rules are apparently universal, the interpretation of these rules is as varied as the states. This was never made more evident than in the contest between Penn and Chicago teams last year. The Chicago team evidently had a very different idea of the interpretation of the rules from that under which Penn players worked, and this placed is really in the hands of the officials to determine the victors. . .

. . . until the method followed in football, of big interpretation meetings in which officials and coaches get together and determine upon the way the rules are to be enforced, we shall continue to have this unfortunate situation which ought not to exist in a sport so thoroughly appreciated by the public."

|

"College basketball produces no national champion. A winter sport which in some parts of the U.S. amounts to a seasonal hysteria, it is played almost entirely within regional leagues. The argument of each league that it has the best team in the land is more footless than most such controversies, since the strongest teams play on courts of different sizes under rules differently interpreted....."

The few tournaments in existence were primarily regional in nature, such as conference tournaments. For example, the largest, most developed and longest running early tournament was the S.I.A.A. (later Southern Conference) tournament held in Atlanta starting in 1921. Teams from Maryland to Louisiana attended, including most of the schools which later became affiliated with the Southeastern and Atlantic Coast Conferences among others. But the winner of this tournament only claimed to be the "Champions of the South". None of the winners of the tournament claimed to be a "National Champion".

There were a few tournaments with national representation, going as far back as 1904 in St. Louis as part of the World's Fair (where Hiram (OH) College beat Wheaton (IL) College and Latter Day Saints of Salt Lake City) but they were sporadic and did not encompass the entire nation.

One example of a very early tournament which did attract outside teams in the name of determining a national champion was the National Intercollegiate Basketball Tournament held in 1922 at Indianapolis, IN. Six teams were invited; three teams (Wabash, Illinois Wesleyan and Kalamazoo, champions of the states of Indiana, Illinois and Michigan respectively) from the Midwest to go along with Mercer which had been a runner-up in the S.I.A.A. conference tournament from the South, Grove City (PA) from the Western Pennsylvania League and Idaho of the Pacific Coast Conference from the West. The Western Conference (later known as the Big Ten) and Eastern Intercollegiate League chose not to participate. Wabash won the tournament to finish with a 21-3 record. (Years later Kansas was awarded the Helms title for that season.)

There were other occasions when a 'national champion' was to be named based on inviting two teams to compete.

One example occurred in 1908 when the University of Chicago and University of Pennsylvania met for a post-season series. Chicago won both games to claim the championship. The Spalding Basket ball Guide noted the difference in styles of play between the two schools: "The play of the Chicago team was characterized by open passing and evasion of contact, while the Eastern men depended more upon dribbling and a much closer interference game."

In 1920, the University of Pennsylvania (champions of the Eastern Intercollegiate Conference) and the University of Chicago (champions of the Western Conference) once again met in a three-game series designed to designate a national champion. Each team hosted a game on their home floor, with a third game (if needed) to be played at Princeton University. (As mentioned previously, this series was noted by Walter Camp to demonstrate discrepancies in rules interpretations between regions)

The Chicago Maroons won the first contest in Chicago. Penn won the game in Philadelphia, after which Penn students celebrated by throwing bricks and firing shots at policemen while partying through the night. The rubber match was won by Penn, by a 23-21 margin. They later were awarded the Helms title for that season.

|

Another example occurred in 1935 in Atlantic City which hosted a basketball event of two teams. The Louisiana State Tigers were invited to face Pittsburgh in the "American Legion Bowl", in a game touted to be "for the national collegiate championship" despite the fact that Pittsburgh (and arguably LSU) were not considered the top teams in their respective regions of the country. The Tigers won the game 41-37, and determined to call themselves national champions based on the win (although the Helms Award went to New York University).

Probably the closest to being a legitimate and long-standing national tournament which included teams at the collegiate level was the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) tournament, but that tournament involved other amateur teams and thus was not exclusively directed to colleges. Only four collegiate teams won the tournament, Utah (1916), New York University (1920), Butler (1924) and Washburn College (1925). Those collegiate teams which did participate were not necessarily representative of the entire nation.

Setting the Stage for a true Collegiate Championship

|

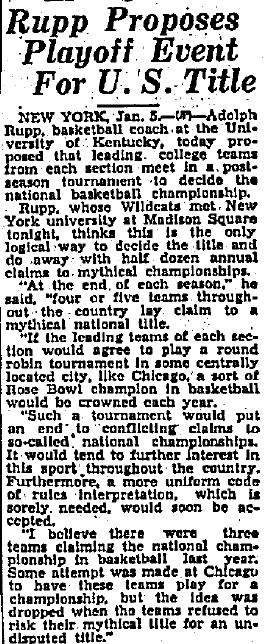

The first such event saw the Notre Dame Ramblers (as they were then known) face the New York University Violets in Madison Square Garden on December 29, 1934, a game the Ramblers lost 25-18. A new world record in attendance was set for a college basketball game with 16,138 fans on hand. The following week, the University of Kentucky travelled to New York for the first time ever and faced NYU, breaking the previous week's record with 16,539 spectators. These two teams were thought to be two of the best in the nation, and the game did not disappoint, with the Violets winning in the last seconds 23-22, the difference coming on free throws after a disputed call.

After the game, Kentucky Coach Adolph Rupp took the opportunity of this early high-profile intersectional game to propose a national tournament. "At the end of each season four or five teams throughout the country lay claim to a mythical national title." said Rupp. "If the leading teams of each section would agree to play a round robin tournament in some centrally located city, like Chicago, a sort of Rose Bowl champion in basketball would be crowned each year."

Rupp's college coach, Forrest "Phog" Allen, supported Rupp's idea and other coaches made similar types of suggestions throughout the decade. Eventually the idea of a national tournament finally became a reality. The NCAA was beaten to the punch, however, first by the NAIA in 1937 and the following year by Ned Irish and the New York's Metropolitan Basketball Writers Association in creating the National Invitational Tournament (NIT) in 1938. The NIT proved popular, garnered great interest and attracted high profile teams from around the country, but it still was a metropolitan invitational, in that top teams from around the country squared off against local metropolitan New York teams.

The NIT encouraged the National Association of Basketball Coaches (NABC) through the efforts of coaches such as Forrest "Phog" Allen, Harold Olsen, Arthur Lonborg and Tony Hinkle among others, to host their own tournament in 1939 with the championship in Evanston, IL (nearby Chicago). The NCAA took over the tournament from the NABC the following year.

The NCAA Tournament was in many ways different than the NIT, which initially made the NCAA's event more difficult to generate fan interest but paved the way for a truly national tournament. For example, the NCAA chose representatives from each of eight pre-defined geographic sections of the country to ensure that the entire country had an opportunity to be represented. Additionally, games were played at 'neutral' sites which in theory gave every team the same opportunity for winning. (Unfortunately this also resulted in relatively lackluster attendance and thus revenues.)

Both the NIT and NCAA grew in stature and importance during the 1940's as interest in the game of basketball itself skyrocketed. By the early 1950s, as the NCAA expanded its field and took more control over its members autonomy in choosing which tournament to participate in, it became clear that the NCAA Tournament was the preeminent national tournament and the winner was considered the undisputed national champion (for better or worse).

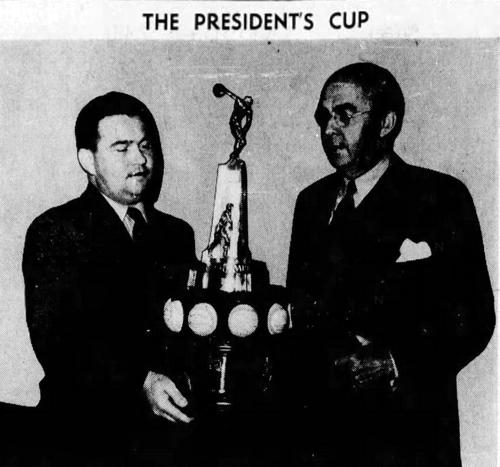

One person who was keenly interested in not only recognizing current champions but going back and recognizing past teams and players was Willrich (aka Bill or William or W.R.) Schroeder. A semi-pro baseball player and avid collector of sports memorabilia since his boyhood, by the mid-1930's Schroeder had amassed so many sports-related items that he needed to find a sponsor to house and potentially display his wares. After trying and failing for four years to interest over sixty businesses to underwrite his passion, Schroeder finally found a sympathetic ear in the person of Paul Hoy Helms, owner of the Helms Bakery Company in Southern California. At one time Helms Bakery Company was reported to be the largest home delivery bread company in the country.

Helms was raised by his uncle, Major League Baseball player William "Dummy" Hoy and grew up around the game. Helms thought that Schroeder's interest in honoring past achievements in sport meshed well with his own desire to honor present-day athletes and to inspire youth to become the stars of the future. Helms also recognized what Schroeder knew, that 'when a man gives another man a trophy, the honorer is honored along with the honoree.' (Los Angeles Times, "A Hobby That Became a Way of Life," August 13, 1980) and saw that the added publicity and good-will would be a benefit to his bread business.

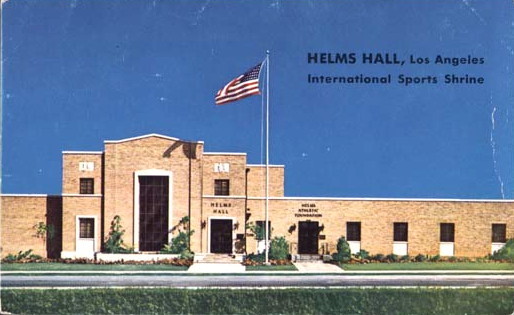

The two started the non-profit Helms Foundation in 1936, with Schroeder installed as the managing director. All sports were represented but the foundation quickly associated itself closely with the Olympic Games, which had recently been held in Los Angles in 1932, and would enjoy a long relationship with the Olympic movement. In 1939 a museum was opened to display many of the wares Schroeder had collected and continued to accumulate. This was later moved to a new facility, Helms Hall, in 1948. In addition, a library was opened for researchers and fans alike. These proved a very popular destination, especially for young boys interested in sports.

|

An early achievement of Schroeder was to bring the various sports editors from around Southern California together to vote on a single set of prep all-star teams, rather than a different set for each newspaper. This practice lasted for many years and continued even after Schroeder's death in 1987.

Through the Helms Foundation, Schroeder was able to fulfill his desire to provide a place to not only display his collection but to share his interests with others. Schroeder became well known for awarding trophies to athletes, not just in the Southern California region but nationally and internationally also.

|

But Schroeder was not content with merely honoring the athletes of the day, he also felt strongly that past athletes, many of whom never received their just deserts due to a general lack of publicity and information access, also deserved recognition.

To that end, Schroeder went beyond the information he had acquired up to that time and with Helm's permission Schroeder began to study in greater detail the great basketball players and teams of the past. This involved contacting coaches and sportswriters from all across the country. For his work on past basketball teams, this reportedly took place over two years, including approximately six months of intensive research. (Picking past champions for football was a project done by the Helms Foundation in 1948, although others had already been doing it for decades.)

Finally in February of 1943, the first installment of the Helms selections were completed and sent out to select sports editors around the country. Included were picks from 1920 to 1942 inclusive. Oddly enough, the booklet was titled "Helms Athletic Foundation Collegiate Basketball Record Part II." The reason given for this was it was intended to include teams from earlier years back to 1900, however this was put off until a future time. As it happened, Part I, which listed teams from 1901 to 1919, didn't make its appearance until 1957.

A search of responses from that time period show that a few writers commented on the work and generally found the selections to be satisfactory, although the focus was on local athletes named rather than nationwide. No articles have been found challenging the results. But there was no universal outpouring of support or even notice of the work (as some have assumed). In fact, the work probably went unnoticed by a large number of people, including many of the very players who had been named for honors. There are many examples of players who didn't realize their team had even been honored until decades later.

Nor was there universal acceptance of the picks as official (another theory some people assume to be true). As sports editor John Mooney wrote in 1957 upon the publication of Part I "the list isn't 'official,' but it represents a tremendous amount of research and study in trying to evaluate honestly the thousands of basketball stars over almost 50 years of the game." (Salt Lake Tribune, "Helms Foundation Honors Cagers" October 30, 1957.)

The Helms Foundation continued to name award winners for present-day teams. Early on there were some discrepancies between their choices and the winner of the NCAA Tournament (described below) although later the Helms picks aligned completely with the NCAA Tournament winner, to the point that it became a formality.

In 1957, Paul Helms Sr. died of cancer at the age of sixty-seven. The company was later run by his son, Paul Helms Jr., however the growth of supermarkets and urban sprawl in Southern California made bread delivery a more difficult business environment and the company's fortunes waned.

The Helms Foundation was a misnomer as there actually was no foundation in place to sustain the operation, instead the foundation was subsidized completely by the bakery's operations. When the Helms Bakery ceased operations in 1969, it soon became apparent that the trustees of his estate were no longer interested (nor capable) in underwriting the Helms Foundation, its museum or library. Schroeder went in search of a new sponsor and in 1970 Citizens Savings Bank stepped in and agreed to sponsor the foundation. They moved the site to their offices near Los Angeles International Airport.

When the sponsorship with Citizens Savings ended in 1981, Schroeder considered moving the museum out of Los Angeles but was rescued by Olympic Organizing Committee president Peter Ueberroth who first helped attract another bank, First Interstate Bank, as a sponsor and soon thereafter folded the operation into the Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles. As part of the surplus funds from the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games, the Amateur Athletic Foundation (later renamed in 2007 as the LA84 Foundation) was formed and endowed with a mission to promote youth sports in Southern California.

Schroeder died in 1987. By that time, the holdings which he had spent a lifetime acquiring and making available to others was at least secure. From the current LA84 website: The LA84 Foundation operates the largest sports research library in North America, the Paul Ziffren Sports Resource Center. It is a state-of-the-art research facility and learning center dedicated to the advancement of sports knowledge and scholarship. The Foundation also maintains a sizeable collection of historic sport art and artifacts much of which was inherited from the former Helms Athletic Foundation Sports Hall of Fame."

![]()

Rebuttal

| Issues in Naming Early-Era Champions | Questions of Authority | Vulnerability | Evidence of a Single Voter | Championships vs. Titles | The Final Word |

The Issues in Naming Early-Era Champions

|

There are numerous reasons for this, including the fact that during the early part of the century, the lack of media and information technologies (i.e. very little radio, no television, no satellite, no internet), lack of easy travel and general lack of interest in the sport itself (resulting in sporadic media coverage at best and incomplete record-keeping and crude statistics) made it extremely difficult for anyone to make an objective or accurate determination of the best teams and players in the country for any given year.

Exacerbating this situation was the fact that schools generally only played locally and there were very limited opportunities to play games outside their own regions, much less nationally. This situation gave rise to the eventuality of particular schools dominating their region or conference, but determining how well they would have fared against schools from other regions is anyone's guess. Another major problem is the relatively small number of games played along with the lack of uniform scheduling among teams.

It is these last two limitations (lack of diversity and number of games in schedules) which makes it virtually impossible, from a statistical standpoint, to compare and rank teams from early in the century. (Although some have taken on the challenge.) But even today, after painstaking research to recover lost records and determine the best set of statistics possible and with the full use of computers to store and analyze available data, these limitations cause even the best attempt to be heavily dependent on subjective criteria, if such criteria is even available.

In the 1940s and 1950s when the retroactive Helms picks were being made, one factor in their favor was that many of the players, coaches and others who witnessed their play were still alive and presumably able to vouch for at least their stake in history. But in many ways the lack of reliable records was even a bigger problem then, to go along with the question of how representative and how broadly these witnesses' knowledge was, in relation to the numerous other players who they hadn't seen (again, the lack of television and a national tournament being key).

These issues lead one to conclude that while it is useful to attempt to rank teams from this time period, and it is certainly a worthy cause, the expected accuracy of the picks and thus the amount of credence one should give their choices is limited. This is true particularly in comparison to more recent times where the expansion of schedules, relative ease of games outside regions and the formation of National tournaments expressly designed to crown national champions, has made it significantly more feasible to evaluate and determine the top teams (although even with all that going for it, there is still oftentimes disagreements over who is the best team.)

| Retroactive Picks of Early Collegiate Teams (With Official NCAA Record*) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Helms Picks School (Record) | Premo-Porretta Consensus Picks School (Record) | |

| 1901 | Yale (10-6) | Bucknell (12-1) | |

| 1902 | Minnesota (15-0) | Minnesota (15-0) | |

| 1903 | Yale (15-1) | Minnesota (13-0) | |

| 1904 | Columbia (14-0) | Columbia (14-0) | |

| 1905 | Columbia (13-0) | Columbia (13-0) | |

| 1906 | Dartmouth (16-2) | Wabash (17-1) | |

| 1907 | Chicago (21-2) | Williams College (15-1)** | |

| 1908 | Chicago (24-2) | Wabash (24-0) | |

| 1909 | Chicago (12-0) | Chicago (12-0) | |

| 1910 | Columbia (11-0) | Williams College (11-0) | |

| 1911 | St. Johns (NY) (14-0) | St. Johns (NY) (14-0) | |

| 1912 | Wisconsin (15-0) | Wisconsin (15-0) | |

| 1913 | Navy (9-0) | Navy (9-0) | |

| 1914 | Wisconsin (15-0) | Wisconsin (15-0) | |

| 1915 | Illinois (16-0) | Illinois (16-0) | |

| 1916 | Wisconsin (20-1) | Wisconsin (20-1) | |

| 1917 | Washington State (25-1) | Washington State (25-1) | |

| 1918 | Syracuse (16-1) | Syracuse (16-1) | |

| 1919 | Minnesota (13-0) | Navy (16-0) | |

| 1920 | Penn (22-1) | Penn (22-1) | |

| 1921 | Penn (21-2) | Missouri (17-1) | |

| 1922 | Kansas (16-2) | Missouri (16-1) | |

| 1923 | Kansas (17-1) | Army (17-0) | |

| 1924 | North Carolina (26-0) | North Carolina (26-0) | |

| 1925 | Princeton (21-2) | Princeton (21-2) | |

| 1926 | Syracuse (19-1) | Syracuse (19-1) | |

| 1927 | Notre Dame (19-1) | California (14-0) | |

| 1928 | Pittsburgh (21-0) | Pittsburgh (21-0) | |

| 1929 | Montana State (36-2) | Montana State (36-2) | |

| 1930 | Pittsburgh (23-2) | Alabama (20-0) | |

| 1931 | Northwestern (16-1) | Northwestern (16-1) | |

| 1932 | Purdue (17-1) | Purdue (17-1) | |

| 1933 | Kentucky (21-3) | Texas (22-1) | |

| 1934 | Wyoming (26-4) | Kentucky (16-1) | |

| 1935 | New York University (18-1) | New York University (18-1) | |

| 1936 | Notre Dame (22-2-1) | LIU-Brooklyn (25-0) | |

| 1937 | Stanford (25-2) | Stanford (25-2) | |

| 1938 | Temple (23-2) | Temple (23-2) | |

| 1939 | LIU-Brooklyn (23-0) | LIU-Brooklyn (23-0) | |

| 1940 | Southern California (20-3) | Indiana (20-3) | |

| 1941 | Wisconsin (20-3) | LIU-Brooklyn (25-2) | |

| 1942 | Stanford (28-4) | Stanford (28-4) | |

(record came directly from school). ** - from research by Phil Porretta. | |||

As alluded to earlier, when Schroeder released his Helms picks in the early 1940s, the choices were not universally accepted as being definitive. It's important to remember the time frame as one reason why.

Even though the NCAA Tournament had been established, in the 1940's both the NCAA and NIT sported relatively small fields of teams, albeit typically with impressive credentials. The NCAA was a more representative tournament geographically, however the NCAA membership did not extend to all major colleges as it does today. (For example many religious-based schools and small colleges were not members of the NCAA at the time.)

The NIT, for its part, was an attractive destination for many of the invited teams which paid well and promised national exposure and a trip to the bright lights of New York. However the NIT also suffered from a lack of national representation as during that era NIT fields were tilted toward East Coast teams.

So despite the institutional support that was behind the establishment of the NCAA Tournament, there was still some uncertainty at the time as to who the best team in the land was. [And for better or worse, subsequently as the NCAA Tournament steadily gained preeminence and became the sole source of naming the national champion, winners of the NCAA Tournament during those early years were given the same level of honor.]

The retroactive Helms choices from that time period did vary somewhat from the NCAA Tournament champion. In 1939 Oregon won the inaugural NCAA Tournament but the Helms pick was Long Island University. In 1940, Indiana won the NCAA Tournament while the Helms pick was the nearby University of Southern California. Subsequent discrepancies between Helms Picks and NCAA champions (in parentheses) included 1944 Army (Utah) and 1954 Kentucky (LaSalle), so there still appeared to be a level of independence at the time to vote for teams that were considered worthy despite not winning the NCAA crown. However, that streak of independence seemed to vanish in later years as the Helms became nothing more than a rubber stamp for the NCAA champion.

Before the NCAA and NIT tournament existed, it's expected that there was even more of a difference of opinion over team's credentials, even with the work of Schroeder. One illustration of this is the fact that of the handful of teams prior to the creation of the NCAA Tournament which claimed to be 'national champions' (many mentioned above) at the time, only a few of them match with the Helms selections.

Additionally, there have been alternative attempts at ranking some of these early teams, including Dick Dunkel Sr. who began ranking sports teams in 1929 and has historical indexes for college basketball of his Dunkel Index going back as early as the 1936-37 season. [Dunkel's results differed from the Helms retroactive picks in 1937 (Notre Dame), 1939 (Oregon) and 1940 (Indiana) when considering retroactive picks. No Dunkel result is available for the 1938 season.]

More recently extensive work by Patrick Premo and Phil Porretta (first individually and later collaboratively) has been done to research and rank teams going back to the very early era of the game, not only picking the top team each season (as Schroeder did) but choosing a large number of teams and ranking them against each other. Their results haven't always coincided with those of the Helms Foundation either. Of the forty-two teams which encompass the retroactive choices made by the Helms Foundation, twenty-five times the Helms choice matches that tabbed by the Premo-Porretta Consensus ranking. (Suggesting that many of the Helms choices were indeed reasonable.) In contrast, seventeen times was another choice made for the top team. (Suggesting that there is still significant room for disagreement with the Helms selections and thus they should not be dogmatically accepted.) [See the table to the right which shows both the Helms picks and the consensus picks between Premo and Porretta's work.]

The Vulnerability of Helms Titles

Beyond the above reasons which cast doubt as to the authority of the Helms Foundation (or anyone for that matter) to accurately determine the best teams from those early years, there is one piece of information which is critically important, but oftentimes overlooked.

This revolves around the fact that those who seem to want to put a lot of stock into the Helms Foundation's findings, presume that the decisions were made by a geographically diverse and knowledgeable group of basketball experts. Most references to Helms on the internet and in reference books refer to a so-called 'Helms Committee'.

The problem with this claim is that there is no evidence whatsoever of the existence of a Helms Committee for these retroactive picks. Indeed there was a group of local sports editors and writers who periodically got together to award athletes in various Southern California sports (mentioned earlier in this article) and potentially later there were likely staff members who assisted Schroeder in making choices for the present season, but not for retroactive picks.

If anything, the little evidence that is available suggests that Schroeder himself was the one and only member of the 'Helms Committee'.

The Evidence of a Single Voter

If there ever was a time to mention the individual make-up of a Helms Committee, it would be when the retroactive picks were 'published'* in 1943. But the one-page preface of the booklet made absolutely no mention of a committee, and didn't identify any individual(s) who made the choices. Instead it described more the criteria of how selections were made and the types of people who were consulted.

"The Helms Athletic Foundation selections, in every instance, have been based upon actual performances by players and teams, and not upon reputation. Selections have been made only after many months of exacting research, and careful study of the performances of thousands of players and hundreds of teams."

. . .

Helms Athletic Foundation is grateful to those coaches, sports writers, college news bureau directors, and authorities who provided fact, information and recommendation, in relation to the collegiate basketball research which has been conducted by the Foundation for the past six months."

* JPS Note: I say 'published' in quotes because the 26-page booklet that was sent out to sports editors around the country was more akin to a press release than an actual publication which would be catalogued and retained by libraries. This helps explain why it literally took years before I located (through the tip of a reader of the website) a copy of the actual set of pages.

Nor was there reference to a committee when a sparse number of sportswriters made mention of receiving the booklet in February and March of 1943. None questioned who exactly made the choices at the time (or apparently since), although Schroeder was always prominently mentioned. Said Jack Durkin in an article in the Syracuse Herald-Journal (February 15, 1943) "Collegiate basket ball Hall of Fame selections, and citations of outstanding coaches are among other interesting features in the booklet which came from Bill Schroeder, managing director of the Foundation, in Los Angeles, after an exhaustive six months' peppering of coaches and sportswriters for information."

In 1948, retroactive football picks were also chosen by the Helms Foundation. Unlike basketball, making retroactive football picks was not as groundbreaking an exercise since numerous people and organizations had been honoring football players for many years prior, including retroactively. But an interview with Schroeder in a 1967 article in Sports Illustrated (September 11, 1967) revealed more about who exactly made the retroactive football picks than any source about the basketball retroactive picks had.

According to the article:

Schroeder himself confirmed that he made the retroactive picks for basketball in a report entitled Helms Award Report which was found in the Helms Foundation records at the LA84 library. This document, written by Schroeder in the third person, reviewed many of the accomplishments of the foundation and listed the awards that Schroeder thought should be continued, although the date the document was actually written is unknown.

Schroeder writes in a section of the report regarding the retroactive basketball picks "Schroeder also designated College Basketball National Championship Teams, dating back to 1901 -- something which had never been done before." Later in the same document he also confirmed that the choices for currently named teams was also made by him when he wrote: "The College Basketball All-America Team, Player of the Year, and National Championship Team selections are made by Schroeder, without the assistance of the Athletic Foundation's Awards Board, following exhaustive research and contacts with college [sic, colleges] throughout the country."

|

|

Given all that is known about Schroeder and his interests, along with the various comments through the years, it's not surprising that Schroeder himself was the person who took on the task, and while he certainly made great use of his sources and contacts throughout the country, it was he himself who ultimately made the decisions as to who made the teams and who didn't. You can't expect anything less from the man that Paul Helms himself once described as "the person who is the life and soul of the Helms Athletic Foundation." (UPI, September 26, 1961).

Note that I disagree with Featherston's assertion that Schroeder did not take advice from anybody. Based on Schroeder's claims about the process and the acknowledgement of a few sportswriters at the time, it is apparent that he did indeed contact numerous people and asked for their opinions. But I do agree with Featherston's overall conclusion that there was no Helms Committee and Schroeder himself ultimately determined the picks in the end.

![]()

Postscript

Championships vs. Titles - Why the Distinction Matters

|

When one thinks about the specific essence of the two terms and consults standard definitions, it is clear that the two are distinct, albeit connected entities. A 'championship' is something that is won, most generally on the field of play against direct competition. A 'title' is something that is given or awarded by someone else, in honor of an achievement or as a designation of being considered the best at something.

Given the above, it's not unexpected that in the case of the NCAA Tournament, where a team wins a championship game and they are crowned champions and the team is given the TITLE of "NCAA National Champions", that the use of title and championship becomes blurred. This is because they often come hand in hand with each other.

So while it is generally true that winning a championship also involves a title being associated with it, the converse does not always hold. In many cases, a title can be given without a formal championship or competition being held at all. In other words, being awarded a title does not necessarily confer that a championship was even present, much less attained.

In the case of collegiate basketball, there are actually many titles which can be claimed, some which are associated with winning a tournament (NCAA Tournament, NIT tournament, Conference tournament etc.) and some which are not (Associated Press #1, Highest Attendance, top Sagarin Rating). The latter, do not constitute a championship. It is into this group that the Helms title falls.

![]()

As someone who has for a long time been interested in the history of collegiate basketball, including basketball from the very early eras, I appreciate and applaud the work that Bill Schroeder (among others) did in researching, recognizing and awarding the numerous players, teams and coaches from that time period. Without his work, there certainly would be less recognition and knowledge of some of these early teams and players, and that is something to be commended.

However, I also believe in historical accuracy and it is important to recognize that while the Helms picks have gained stature through the years, especially as more people learn of it through the internet, in the end it is the opinion of one person, albeit a person who made a commendable effort. Beyond that, it is an opinion about teams which played during an era when due to factors outside their control (such as minimal schedules, lack of intersectional play, minimal statistics etc.) it is likely impossible to ever know (or accurately assess) the true strength of the teams in question.

That's not to say that because Schroeder's picks were made by a single individual, that his choices are not important. They are historically relevant and do hold a place of honor and demand an appropriate level of deference. But the circumstances of a single individual retroactively choosing who was best from earlier eras underscores the fact that his choices were not authoritative under any definition. In fact, given the multitude of obstacles in place at the time and still today, it is valid to question whether ANY person or group will ever be able to authoritatively know who the best team was for any given season during that early era.

In the end, the Helms title should be recognized for what it was: a title retroactively given to the best team in the country as determined by Willrich Schroeder, for a time period where there were significant obstacles present in accurately determining who the best team was.

If schools want to recognize their teams by mentioning the Helms titles and hanging banners, that's their right and prerogative. In fact I believe they certainly should recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of past teams, since most fans of schools would never know about them unless they're mentioned somewhere. But in doing so, schools should be accurate by at least noting that the award is from the Helms Foundation, and preferably provide additional background information about who and how the choices were made, including recognizing the fact that many of the choices were made years or even decades after the fact.

To suggest or infer that these titles are synonymous with National Championships, as they are known today, is disingenuous at best. This is especially true when dubious assumptions and unsupported claims are used to support this theory or to make Schroeder's picks more important or authoritative than they actually were at the time.

Given the many misconceptions that have grown up over the years concerning Helms titles, hopefully this article has shed some light over the issue and help to set the record straight.

![]()

Return to Kentucky Wildcat Basketball Page.

Last Updated November 9, 2010.

Note, I would like to thank Phil Porretta, Patrick Premo, NCAA head statistician Gary Johnson, the person who goes by the name of "The Old North Statesman", the LA84 Library (which holds the former records of the Helms Foundation) along with numerous other historians, sports information directors, sportswriters and fans alike over the years. Please send all comments, additions or corrections to